NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | LNG | Markets | NGI All News Access

Growing U.S. LNG Market ‘Needs New Instruments’ to Successfully Navigate Future

As the United States continues to bolster its position as a leading liquefied natural gas (LNG) supplier, “evolutionary and multi-layered changes” taking place in the global gas market will require the country to move away from long-held business practices and procedures, according to one expert.

At a Senate hearing last Thursday called to explore the increasingly important role of U.S. LNG, senior fellow Nikos Tsafos of the Energy and National Security Program Center for Strategic and International Studies said multilateral organizations have played a central role in governing some markets that include crude and nuclear energy. However, the institutional arrangements for natural gas are far less developed.

Information transparency and data availability are poor, at least compared to oil markets, according to Tsafos. Concepts of energy security and resilience also vary, even among advanced economies, and there are few shared metrics on how to measure energy security, much less enhance it.

“This new gas market needs new instruments,” he told the panel.

The growth in global gas volumes has increased the complexity of the markets. In the early 2000s, only around 10 countries exported LNG and 10 countries or so imported gas. “Trade routes were simple and routine,” Tsafos said. “Most LNG flowed either within the Atlantic and Pacific basins, or from the Middle East to the Pacific.”

By last year, however, there were 19 exporters and 37 importers, with importers in particular, growing sharply. Ten countries began to import LNG between 2013 to 2018, according to Tsafos. While intra-regional trade continues to dominate, new trade routes have been created and continue to be created with the rise of Lower 48 exports, as well as LNG shipped from the Arctic.

The structure of the LNG market is shifting as well. Historically, most gas was traded via long-term contracts; short-term contracts accounted for a mere 5% of all volumes. Over time, the short-term market has taken a bigger role, accounting for almost one-third of the trade since 2011, according to Tsafos. “This shift has had profound implications for gas pricing and energy security.”

However, the short-term market for LNG currently makes up less than 4% of the world’s gas consumption, so it does not represent the gas market more broadly, he said.

Tsafos, who earlier in his career led PFC Energy’s global gas research, said global operators are betting billions to enable the next wave of LNG supply, likely to be bigger, more diverse and “perhaps more politically complicated” than the initial wave. The United States will remain competitive throughout the process but it may not dominate the market.

“Instead, we can expect, over time, a market dominated by the United States, Qatar and Australia, with Russia in fourth place,” Tsafos said.

Given the growing U.S. role in the global LNG space, Sen. Angus King (I-ME), said he was concerned about the potential impact on domestic consumers. King noted the rising cost of natural gas to Australian consumers, who have seen prices dramatically increase over the last decade and face potential shortages — despite robust gas exports.

King said he was comfortable with 6 Bcf/d of domestic exports currently heading overseas, and even up to around 10 Bcf/d of exports. However, the 40 Bcf-plus of projects approved or in the queue is “totally against the idea of what is in the public interest. This is a grave concern to me. We’re making a historic mistake.”

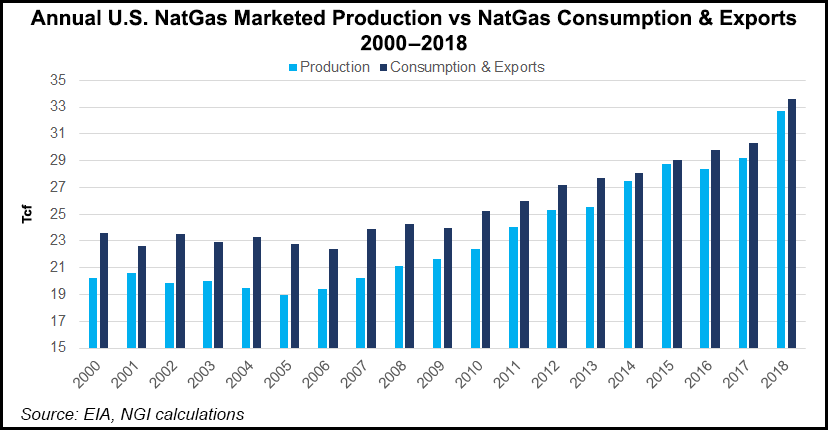

However, the Department of Energy’s Steven Winberg, assistant secretary for fossil energy, said rising gas costs in Australia are mostly because of inadequate infrastructure to demand centers, not from an increase in exports. Winberg also touted the robust production growth in Lower 48 gas growth, which is expected to keep a lid on prices. This year’s gas output is set to exceed 2018 by 10%. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) has projected that dry natural gas production will reach more than 111 Bcf/d by 2040 and 119 Bcf/d by 2050.

“We’re just climbing the learning curve on unconventional oil and gas production in the United States,” Winberg said.

Benchmark Henry Hub prices during the first six months of this year are lower than last year’s average spot price, he said. EIA is projecting prices to remain below $3/MMBtu through 2020 while the New York Mercantile Exchange futures curve reflects sub-$4 gas through 2030.

Nevertheless, King said arguments negating an increase in domestic gas prices when demand is set to surge to 50% of production “does not pass the straight face test. And if we get to a point where natural gas prices are internationally set as a commodity, we’re sunk.”

He called for studies to assess the elasticity of demand and potential impact to prices, rather than “warm, fuzzy assurances” from the industry that prices won’t increase to levels that would harm consumers.

Winberg said five studies have been completed to date, including four that were completed under the Obama administration and the last of which was completed in 2018. The last study significantly broadened the scope of the U.S. LNG exports under more than 50 scenarios, including those that were “very unlikely extremes,” according to researchers.

“All five concluded the overall economic benefit to the United States was a net positive,” Winberg said.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |