NGI All News Access | E&P | Markets

Deepwater, Tight Oil Found Moving Closer Cost-Wise on Development Spectrum

The rapid improvement in efficiencies to produce deepwater oil and gas, which usually has taken years and millions of dollars, has put the expensive offshore within reach of tight/shale oil development costs, according to Wood Mackenzie.

Deepwater and unconventional oil are two of the upstream sector’s biggest growth areas, but they often are considered to be at opposite ends of the development spectrum.

“Deepwater represents large, expensive and complex long-cycle projects best suited to Big Oil. In contrast, tight oil offers flexible short-cycle opportunities more favored by nimbler independents,” the Wood Mackenzie team noted.

However, each sub-sector has undergone a rapid transformation over the past few years, and many of the former industry assumptions no longer hold water.

“In both deepwater and tight oil, costs have come down, while development techniques have improved, allowing vast new reserves to breakeven under $50,” said Asia Pacific upstream director Angus Rodger.

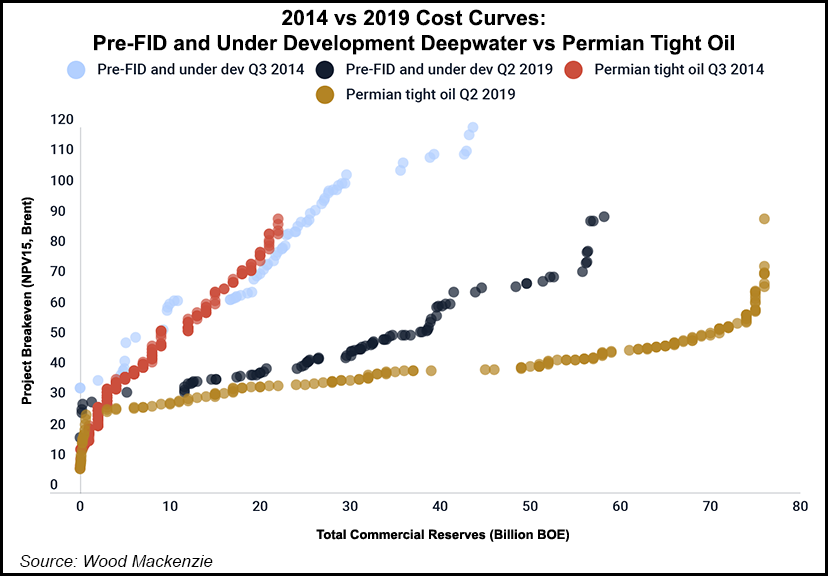

Around mid-2014, 9 billion boe of undeveloped Permian Basin tight oil had an oil price breakeven under $50/boe, compared with 5 billion boe in pre-final investment decisions (FID) deepwater, he said.

“By mid-2019, 33 billion boe breaks even under $50/boe in deepwater, versus a whopping 66 billion boe in the Permian. The latter dominates the pre-FID future cost curve for oil, which is staggering, given it is just a single basin.

“Tight oil’s progression from cottage industry to industrialization is primarily a Permian story, but it is still in its early stages. It used to be all about price-responsive flexibility and well-by-well economics. Now scale is the key differentiator. ”New’ tight oil is industrialized, and that requires more capital and infrastructure, and longer cycle times.”

At the same time, the deepwater industry has been undergoing a reinvention as costs are cut, along with cycle times and breakevens.

The main beneficiaries are a “handful of advantaged sweet spots” that include Brazil, Guyana and the Gulf of Mexico (GOM).

For example, BP plc in late 2016 sanctioned a “leaner” $9 billion Mad Dog Phase 2 project for the GOM. The second phase of Mad Dog’s costs were trimmed by 60% from original estimates. Last year a unit of Royal Dutch Shell plc sanctioned Vito, a deepwater development in the GOM, which it estimated had a forward-looking, breakeven price of less than $35/bbl.

“With a lower-cost developmental approach, the Vito project is a very competitive and attractive opportunity industry-wide,” said Shell Upstream Director Andy Brown said at the time. “Our ability to advance this world-class resource is a testament to the skill and ingenuity of our development, engineering and drilling teams.”

The onshore and deepwater are vastly different, but there are signs of convergence, according to Wood Mackenzie.

“Deepwater is trying to slim down and shorten its investment cycle to offer a viable alternative to tight oil. And the Permian going the other way, scaling-up capital spend, project footprint and value extraction,” analysts noted. This plays into the hands of the majors, which can use their deep pockets and big project capabilities to lead the next phase of tight oil development.

“There are other similarities too,” Rodger said. “At present, both currently produce around 7.5 million b/d, and each is poised for a sustained period of rising output. Both themes are growing, but tight oil — with its underlying low-cost resource base — is growing faster.”

Permian development philosophy is evolving, and projects today are different than even a few years ago. Wells formerly were drilled on smaller pads, laterals were shorter, completions “less aggressive” and subsurface models were in flux constantly. However, after drilling more than 10,000 horizontal wells in the wide basin, industry has zeroed in on where the best rock is.

“The focus has switched to exploitation, increasing recovery and improving incremental economics,” Rodger said. “And engineers discovered that bigger really is better. Experiments proved that well economics improved with more aggressive completions and longer laterals.

“Once big became beautiful, the stage was set for the industrialization of the Permian. Pads doubled, then tripled in size. Beneath them operators were targeting every producible zone with an onslaught of drilling.”

The updated approach, however, “requires considerably more capital, planning and infrastructure than the well-by-well model, but the added complexity and upfront capital are worth it if economies of scale can be successfully delivered. And it makes the unconventional model start to look considerably more conventional.”

Rodger said it may be difficult to conceive how deepwater could be more like tight oil. The nature of deepwater hasn’t fundamentally changed, he said, but the investment proposition has.

“There has been an impressive reset of deepwater economics. Pre-FID projects breakevens have fallen 37%, from an average $79/boe down to $50/boe.”

Average development capital expenditures/boe in the deepwater have declined to under $8/boe today from more than $20/boe, he said.

Average development capex/boe has fallen from over US$20/boe in 2013 to under US$8/boe today.”

A step-change has occurred in development philosophies too. To reduce the investment cycle, increase returns and compete with tight oil, operators are focused on bringing fields onstream faster and more efficiently using simpler development concepts that include subsea tiebacks.

“Simpler projects are quicker,” Rodger said. “From 2004 to 2014 the average project took 10 years from discovery to come online. From 2015, the time from discovery to first production has halved to five years. Leading the way are new low-breakeven developments in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico and Angola.”

The success of fast-cycle development techniques deployed by GOM operators that include LLOG Exploration Co. and Kosmos Energy Ltd. has proven bigger isn’t necessarily the only way to create value from deepwater, particularly in U.S. waters.

“Big Oil will be the big winner from the convergence of tight oil and deepwater,” Rodger said. With strong balance sheets that are self-funding at $55/bbl of oil, each has investment optionality, making choices based on risk and return. The majors’ longer-term investment horizon also allows them to invest through the cycle in both deepwater and tight oil.”

In the onshore, the Permian will be central to driving corporate strategies for players of all sizes. Many U.S. independents will need to scale up to compete as industrialization gathers pace but not all have the skills and capital to do so.”

What Wood Mackenzie analysts expect to emerge is a “more concentrated, differentiated corporate landscape,” with operators more focused on their advantaged assets.

“Rationalization will be an especially important strategic theme for those players with large, low-breakeven tight oil and deepwater inventories,” analysts said. “Portfolio high-grading” is expected to create more opportunity for national oil companies, conventionally focused majors and internationally focused independents.

The combined trends may force many of the larger U.S. independents to reassess whether they should have abandoned deepwater and international portfolios.

“Having a diverse inventory of low-breakeven oil opportunities will be key to thriving,” Rodger said, “as the energy transition unfolds — and both tight oil and deepwater have vital roles to play.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |