NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Markets | NGI All News Access

Column: Should Mexico Create a Single Operator of its Pipeline System?

Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following column as part of a regular series on understanding this process, written by Eduardo Prud’homme. This is the tenth in the series.

Prud’homme was central to the development of Cenagas, the nation’s natural gas pipeline operator, an entity formed in 2015 as part of the energy reform process. He began his career at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), worked for 14 years at the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), rising to be chief economist, and from July 2015 through February served as the ISO Chief Officer for Cenagas, where he oversaw the technical, commercial and economic management of the nascent Natural Gas Integrated System (Sistrangas).

The opinions and positions expressed by Prud’homme do not necessarily reflect the views of NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index.

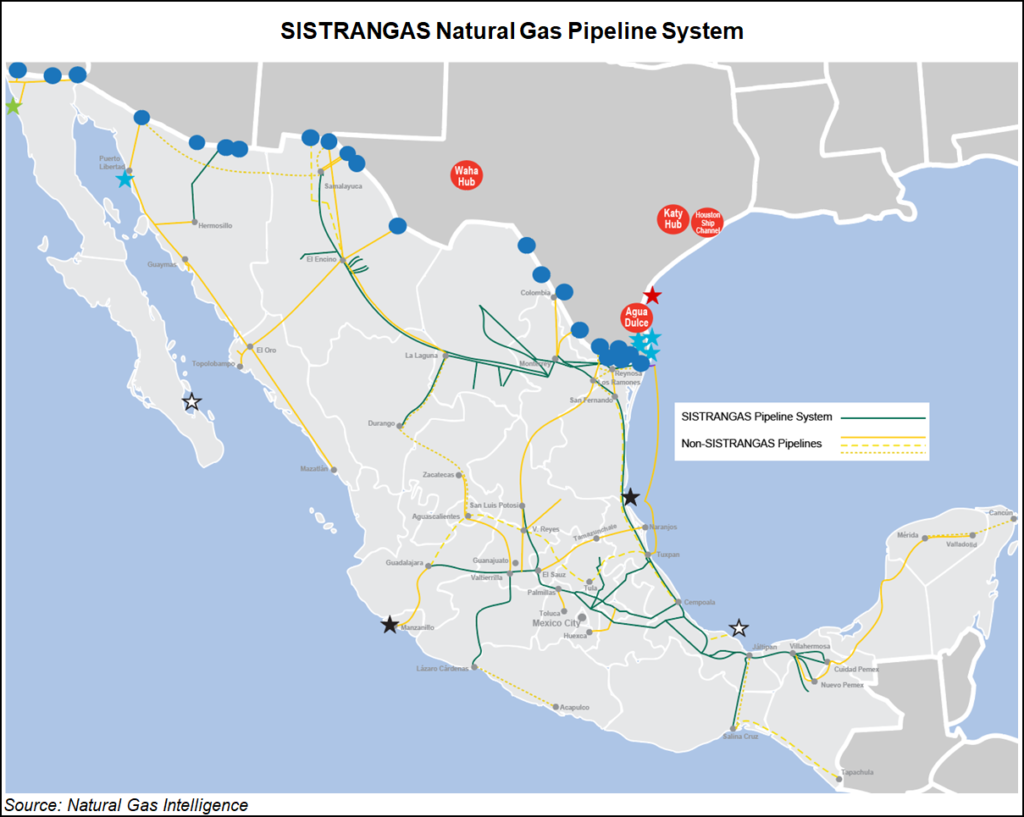

The economic model for natural gas transportation in Mexico is a hybrid between the European and U.S. models. The country has an integrated system, Sistrangas, whose capacity is managed by Cenagas, and which resembles the European approach.

Simultaneously, there are several gas pipelines operated by private Mexican and foreign companies. The Sistrangas emerged from the old national pipeline system SNG, which was transferred from Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) to Cenagas in 2016. The isolated systems were developed separately.

The question now being asked by the new government is whether both systems should fall under the umbrella of a single system manager. This column will explore the debate and explore the pros and cons.

It’s important to note that the two systems were basically formed by two economic agents. The Sistrangas pipes were built by and for Pemex as part of its natural hydrocarbons monopoly in the country, while the private pipelines were mainly anchored by the Comision Federal de Electricidad (CFE), the country’s largest generator of electricity.

As the only agents with the capacity to absorb large-scale commercial risks, the pipeline infrastructure, as well as its routes, dimensions, extraction points and economic conditions were established by the two productive state enterprises, or as denoted in Spanish, their EPEs. This has left little space for industrial users or distributors to develop projects, which in turn has slowed the growth of demand in these segments.

In a simplified way, the movement of natural gas by pipeline is divided into the Sistrangas, a centralized system inspired by the European experience, as well as linear pipelines that operate independently, which are decentralized and whose economic logic is more North American in nature.

In the Sistrangas model, tariffs are universal, with roll-in mechanisms. The costs of the different pipelines are aggregated and assigned through criteria and mechanisms that implicitly entail cross-subsidies between users, depending on the tariff zone in which they are located.

In the pipelines under the North American model, tariffs are based on marginal cost, in which additional use implies incremental costs, be it for an extension in length or an expansion in capacity.

In this way, there is a differentiation in charges. This system protects against increases in costs to anchor users, which pay negotiated rates. Other users pay regulated fees that reflect the cost of providing services, and the marginal cost of additional use.

All pipelines in Mexico are regulated by the Comisión Reguladora de Energía (CRE), are open access, must have electronic bulletin boards and are regulated by the general terms and conditions for the provision of the service.

However, given the existence of these two models, it’s inevitable that contradictions, conflicting incentives and differences in costs will arise in adjoining regions. Even the commercial treatment of capacity is different.

In the Sistrangas, transport capacity is sold point-to-point without the possibility of segmenting journeys. Operational flexibility is derived from the declaration of secondary points, which allows changing the origins and destinations of the gas, but in a limited way without the inclusion of intermediate points.

In the other system, tariffs can be defined by individual journeys, which optimizes utilization of the capacity.

The European scheme is preferred by system operators because it allows them to balance the pipeline network in different ways in the face of equipment failures, while the second scheme has commercial qualities that improve the opportunities for shippers.

In terms of incentives, the integrated system manager, Cenagas, is in charge of ensuring the continuity of supply in the Sistrangas, and therefore responsible for maintaining system balance even if that means purchasing gas to ensure operating conditions. It also must absorb individual shocks.

In a system under the North American convention, the obligations of continuity in the service are conditioned to the fulfillment of each shipper placing the molecule at the beginning of the journey. Their incentives are oriented to fully identify the user responsible for the imbalances to assign the costs of repairing the operational conditions and with a clear message to users that the reliability of the system depends on the individual decisions of each shipper.

One important distinction is that private networks sponsored by the CFE have access to a greater diversity of production basins in the United States. Bottlenecks in the corridor that go from El Encino to Monterrey make it difficult for Cenagas users to have the option of buying gas referenced to Waha as an option.

CFE, being the dominant user in non-Sistrangas systems, thus has operational and commercial flexibility. That said, the integrated network is diverse in shippers as a result of an open season, while in the rest of the pipelines the capacity is controlled by CFE.

This is the state of things the new government of Mexico inherits: two systems, with asymmetric results and with paradoxical balancing conditions.

In response, the new team at Cenagas has expressed the desire to form a national manager to administer not only the Sistrangas but also the capacity of the pipelines anchored by CFE. This initiative is consistent with the goals of the new government in the energy sector. The idea places the state at the center not only of energy production, but also energy infrastructure and market performance.

Sound energy policy should promote efficiency, energy security, competition and a transition towards cleaner energies. The truth is both models can achieve these goals.

Centralized systems provide energy security if operational decisions start from reliable information and proper risk assessment. But in the case the operation does not follow any protocol, centralized decisions can make the system even more vulnerable.

Competition inevitably depends on Cenagas’s ability to ensure effective open access on the system. Contract rules must be fully respected, otherwise centralization will be a catalyst for the return to a vertically integrated monopoly.

In summary, without accountability regarding the objectives to be achieved, centralization will not prove effective to meeting the stated goals.

One of the reasons to create an independent systems manager was to have a large-scale economic agent that was neither a seller nor a buyer of gas. Free of conflicts of interest, it could act as an anchor user for new pipelines. It was designed to serve the market as a whole.

The independent manager is responsible for planning the expansion of the system, the definition of a portfolio of projects, preparation of cost-benefit studies to justify the merit of these projects, planning strategic/social projects and formulation of the corresponding tariff scheme.

Most of the pipelines sponsored by CFE are also considered strategic to national interests, according to the definition of Article 69 of the Hydrocarbons Law. These pipelines must have a design with a minimum 30-inch diameter, operating pressure equal/greater than 800 pounds/square inch, traverse at least 100 kilometers, or have been developed to secure supply, as determined by the Energy Ministry.

Had they been tendered by Cenagas, most likely, the bidding rules would have required that the participants be part of the Sistrangas. Integration is currently a voluntary act. With this in mind, the creation of a manager to overlook the entire system will require significant corporate and regulatory work, as well as technical skill.

The biggest challenge, however, is financial. The integration would mean that Cenagas would take responsibility for CFE payment obligations to the developers of the infrastructure. Such payment would endow it with the right to this capacity, but the cost would have to be either absorbed by the treasury — increasing pressures on public spending — or assigned to the entire set of users on the integrated system.

This would imply a substantial increase in the tariff level.

On the side of tariff design, a rezoning would then be necessary, which implies a technical challenge that may trigger political issues between the different regions of the country.

An essential actor in all of this would be the CRE.

The regulator not only needs to give the go-ahead for the integration, but also to draft the general administrative provisions for integrated systems, including guidelines on the rules of operation that will govern the relations between the manager and the owners and operators of the different pipelines that will make up the integrated system.

These operating rules must bestow upon upon the manager the responsibility to maintain the continuity, reliability and security of the system, and at the same time protect pipeline investors.

A critical step is the willingness of the different transport permit holders to be part of an integrated system. The fundamental question in this area is whether this integration is financially suitable to the owners of the pipelines.

The conventional rates that CFE must pay are the product of a tender process and reflect a financial strategy that may include the expectation of selling excess capacity at a different rate, and according to the cost of providing the service.

If Cenagas intends only to pay the rates negotiated by CFE, it’s important that it doesn’t attempt to manage capacity beyond the maximum daily amount established in the contracts. Otherwise, there may be a significant financial impact on the owners of the infrastructure that may well be interpreted as a de facto expropriation, since the cash flow expectations of the different operators will be impacted.

This issue is especially critical given the current spat between CFE and the consortium of companies that own the Sur de Texas pipeline.

In the end, if we do not follow a cautious, conciliatory and gradual path, the creation of a single manager of the pipelines in Mexico can go from being an idea with merit, to a costly measure in terms of finances, efficiency, and security, but above all in terms of private sector confidence in the industry.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |