NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | E&P | NGI All News Access

Tampico-Misantla Said Key to Reversing Mexico’s Oil, Natural Gas Decline

As engineers from the Mexican national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) struggle to meet production targets that can revert years of declines in production of crude and natural gas, energy expert Alfredo Guzmán has a message to them: “You’re looking in the wrong place!”

Pemex is aiming to boost production in southeastern Mexico, both onshore and offshore, the region whose boom, beginning with the 1976-82 presidency of José López Portillo, once made Mexico the world’s fourth largest oil producer.

But that was then, Guzmán told NGI’s Mexico GPI. The Cantarell oil field that once produced more than 2.2 million b/d of crude, is all but exhausted and Mexican crude output has been halved since its 2004 peak, while gas production has seen a similar fall since peaking in 2009.

Dry natural gas production from the Pemex processing centers continued to fall in May, dipping 10.3% year/year to average 2.192 Bcf/d. Crude output dropped 10.1% to 1.66 million b/d.

“By contrast, in the United States, the Permian Basin has produced more than 4 million b/d of crude and 12 Bcf/d of gas and in a record space of time,” said Guzmán, a founding member of Mexico’s Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH), the upstream regulator.

But Mexico’s oil industry has a card up its sleeve though it seems very reluctant to play it, Guzmán said.

“The irony is that Mexico has a basin that has resources very similar to those of the Permian. It’s called Tampico-Misantla.”

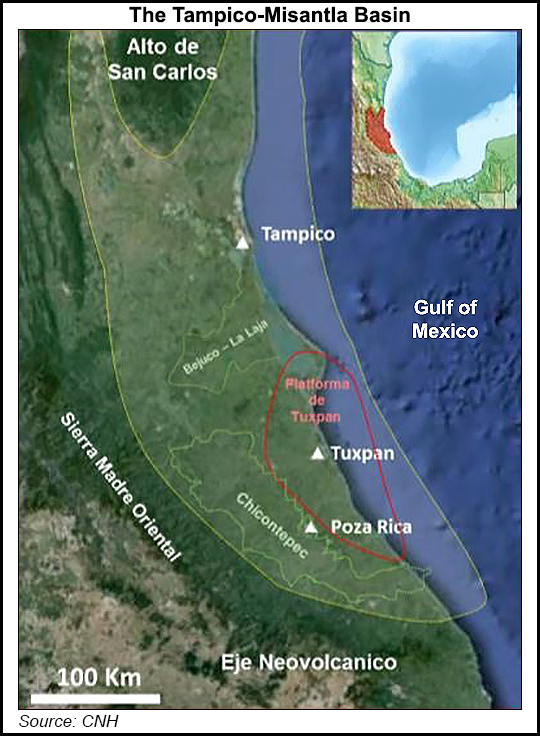

IHS Markit has previously said that the Tampico-Misantla Basin, which extends across east-central Mexico into the shallow waters of the Gulf of Mexico, may be one of 24 global onshore “super basins,” much like the Permian Basin with its myriad reservoirs and multiple source rocks.

The Tampico-Misantla Basin was the cradle of the Mexican oil industry last century. It was first developed by the U.S. and British oil companies that were nationalized in 1938.

“Pemex all but abandoned Tampico-Misantla. The company chiefs were dazzled by their success in the south-east, and they starved Tampico-Misantla of resources,” Guzmán said. He should know. He was head of Pemex’s northern region until the early years of this century. “And as the center of gravity of the oil industry moved to the south-east, northern Veracruz was all but abandoned by the Mexican state and federal governments.”

But Guzmán argues that those who seek to promote a rapid recovery in production of hydrocarbons — as the government of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has promised — should be looking once again at Tampico-Misantla.

Though the potential of both the Permian and Tampico-Misantla is similar, the current results of their production is radically different. Production in Tampico-Misantla today is negligible.

If the growth rate of the Permian could be reproduced in Mexico, Guzmán says, output of Tampico-Misantla could grow by 1 million b/d of crude in less than five years.

But in Mexico doubts over whether hydraulic fracturing (fracking) will continue to be permitted is clouding the horizon for would-be investors, and the Permian owes its success to fracking.

The CNH this week approved the technique for two contracts in Tampico-Misantla. Industry sources say that fracking has been used frequently in Mexico. Pemex’s own 2019 budget includes 3.35 billion pesos, or about $170 million, for three unconventional pilot projects in the Burro-Picachos, Tampico-Misantla and Burgos Basins, and the CNH has sanctioned fracking at four exploration blocks in Tampico-Misantla.

In a Wednesday morning press conference, López Obrador, who has been critical of fracking, said that he would “suspend” the most recent CNH authorizations.

Indeed political uncertainty continues to plague the industry even as the government sets aggressive production targets over the next six years.

In December, the CNH cancelled onshore bid Round 3.3, which would have placed on offer nine blocks targeting unconventional gas resources in the Burgos Basin. It would have been the first auction for unconventional acreage in Mexico’s history.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |