Regulatory | E&P | Infrastructure | LNG | Markets | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

The Energy Wars Part 1: Natural Gas Under Fire as States Favor Alternatives in Climate Policy Push

Part One of Three. (see Part Two; Part Three).

This series analyzes the groundswell of “clean energy” policies being implemented across the country in response to climate change. It examines the implications for the oil and natural gas industry as it confronts society’s growing demands for alternative energy, as well as highlighting some of the viewpoints and technologies shaping the debate at the federal and state levels.

States across the country are moving aggressively to curb oil and natural gas consumption, implementing policies to decarbonize and power their economies with renewable resources in a growing trend that finds the fossil fuel industry taking a more proactive approach to confront an existential threat.

The tenacious drive to reinvent energy policies is likely to cut into oil and gas demand, but to what extent, and at what point, is a matter of debate.

Domestic oil and gas production hit record levels last year and is expected to continue climbing. Spurred by gains in unconventional oil and gas, fossil fuels are helping to grow emerging economies and improve economic conditions worldwide. Meanwhile, since 2008, coal plant retirements have totaled 81 GW across 696 units at 360 plants in the United States, according to one estimate by BTU Analytics LLC.

As coal’s role diminishes, however, environmental groups — and an increasingly wary public concerned about the implications of climate change — have trained their sights on oil and gas. Politicians in states controlled by Democrats and many serving in legislatures with Democratic majorities have taken notice.

State lawmakers are not only proposing energy policies that could eventually have meaningful impacts on natural gas demand, but they’re enacting them, and in some cases, meeting early goals to wean constituents off fossil fuels.

“The success of gas in closing down coal is also the seeds of its own problems,” said former Pennsylvania regulator John Hanger, who served as secretary of the Department of Environmental Protection under Democratic Gov. Ed Rendell. “Because with coal closed down, if you’re serious about climate, all that you have left to reduce carbon emissions is natural gas and oil.”

According to one analysis released earlier this year by the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), one-third of the U.S. population currently lives in jurisdictions that are already targeting 80% emission reductions by 2050. Whether such targets and similar policies are aspirational or reality is a divisive matter.

Like it or not, as coal abdicates its leading role in the nation’s energy mix, oil and gas are becoming public enemy No. 1 in the battle against global warming.

“Producing states need consumption — they need consumers,” Hanger told NGI. “A big chunk of the consumers of natural gas are sitting in states that are moving to reduce natural gas demand. That’s an enormous problem for a producing state.”

The industry, however, is no longer sitting back. It recognizes that more must be done to both shape the narrative and take action to retain a strong role in the energy sector.

“The conversation is changing. It’s the energy conversation that’s changing,” said BP Energy Co.’s Dawn Constantin, senior vice president of marketing and regulatory. She made the comments at the recent LDC Gas Forums Northeast in Boston. The event was dominated by talk of how renewables and political pressure in the region might affect natural gas.

“We’re in this really interesting spot where we’ve got demand growth and lots of needs around the world, but yet society — you and I — want lower carbon, lower emissions, cleaner fuels,” she said, adding that her company refers to it as the “dual challenge.”

It was during the last decade that the International Energy Agency (IEA) declared that natural gas had entered a “golden age,” driven in part by burgeoning unconventional U.S. supplies, the demise of coal and even a desire to stop the planet from warming further.

Today, more than half of the nation’s electricity comes from fossil fuels. Natural gas accounted for 35%, while 20% was produced by nuclear energy and about 17% came from renewables last year, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Globally, natural gas continues to make inroads in nearly all advanced economies, supplying 22% of energy use worldwide and nearly one-quarter of electricity generation, according to the IEA.

In recent years, policies to curb air pollution have driven natural gas demand growth in emerging economies including Asia. Renewables have also seen strong growth across the world, particularly in the power sector, but their uptake, IEA said, has been slower in industry, buildings and transport, minimizing their role in the world’s energy supply to only a small share.

However, renewables are likely to continue accounting for a growing proportion of power generation. In the United States, wind, solar and hydropower are expected to produce 18% of the nation’s electricity in 2019 and nearly 20% in 2020, according to the EIA’s latest Short-Term Energy Outlook. The U.S. power sector is the biggest consumer of natural gas, accounting for 30 Bcf/d of domestic demand last year.

While natural gas continues to expand globally, renewables could account for more than 40% of worldwide power generation by 2040 if policies aimed at cutting emissions continue proliferating, according to one scenario in IEA’s 2018 World Energy Outlook.

“When you draw out the latest thinking around technology and policy, the picture starts to look quite different than what conventional wisdom is — natural gas’ role as a bridge fuel could be a lot smaller than many might expect,” said BCG’s Alex Dewar, who oversees the firm’s Center for Energy Impact, in an interview with NGI.

“It’s actually something that’s quite dramatic for a lot of our clients” working in the upstream, midstream and downstream sectors, he said. BCG is urging companies to plan ahead, reorient their investment plans and safeguard their businesses from the changes that could arise from shifting regulatory policies in the coming years.

“I think ultimately, there’s going to be winners and losers across the board here, and that’s what we sort of urge our clients to think about,” Dewar said. “What’s your exposure to this from the downside or the upside?”

Sociology professor Lawrence Hamilton of the University of New Hampshire has surveyed the public about climate change and renewable energy for roughly a decade now. He’s conducted about 40,000 interviews, asking the same questions mostly of participants in New Hampshire every three months. His data has been benchmarked with five other nationwide surveys over that time, and the results “track amazingly well,” he said.

Hamilton believes that climate change and renewable energy are becoming increasingly important to public opinion. “The most basic thing is whether they think it’s real,” he said of human-induced climate change. Many do, and opinions are shifting. About nine years ago, 50% of respondents believed that climate change was real. Today, that number is in the mid-60s, he said.

Perhaps not surprisingly, politics appear to be the strongest factor influencing people’s opinions, he noted. While there’s a trend among Republicans who are more often supporting climate-oriented policies, the party does not view it as a unifying issue like Democrats do.

The numbers, Hamilton added, are only likely to increase as younger voters come of age or more of them head to the polls. “A belief in climate change and the need for more renewables is rising among all age groups,” Hamilton said. “But it starts higher among the millennials, so they’re really taking this more seriously and always have been.”

House Democrats introduced the Green New Deal in Congress earlier this year to serve as an outline for the federal government to create a program that would help the nation meet 100% of its electricity demand with renewable and zero-emission energy sources. Republicans have largely responded with an innovation agenda to push for funding that would advance carbon capture and sequestration or nuclear technology, among other things.

Given the divide, and the Trump administration’s staunch rejection of climate science, there’s little traction on the issue on Capitol Hill. An omnibus energy bill isn’t likely anytime soon. But states have stepped in to fill the vacuum, with the backing of Democrats who are embracing the climate argument and essentially casting fossil fuels as an enemy of the environment.

It’s not only states taking on the climate mantle; companies, investors and cities are doubling-down on their environmental commitments as well. According to the Sierra Club, 100 communities across the country have committed to transition to 100% renewable energy — including population centers as large as Atlanta, Chicago and Denver. Technology giants such as Apple, Google and Facebook also have expressed strong desires for lower-emitting energy sources to power a digital society, while utilities that power millions of homes such as Xcel Energy have committed to delivering 100% carbon-free electricity to customers by 2050.

“All of these states are being deluged not only by citizens, but companies and investors, saying that it is urgent we act now, and they are acting now. We are seeing that change grow in states every day,” said Ceres CEO Mindy Lubber. The nonprofit works with the private and public sectors on sustainability issues. She made her remarks during a media call in May that was hosted by the World Resources Institute.

Hanger, who also served briefly as policy director under current Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf, noted that 17 states under Democratic control are pursuing anti-fossil fuel policies. They include the six New England states, as well as California, Colorado, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Nevada, Oregon and Washington, he said. The District of Columbia (DC) and Hawaii are also in a similar category.

While 29 states have set renewable portfolio standards, Hawaii was once the only state with the goal of generating 100% of its electricity from alternative energy sources by a certain date. California, New Mexico, Nevada, DC, and most recently, Washington and New York have joined the fold, while others are advancing similar measures.

Washington Gov. Jay Inslee in May signed into law a bill requiring 100% clean energy by 2045 that his office claims “puts the state on a path to entirely eliminate fossil fuels from electricity generation” by that time. Other states are advancing strong climate protection bills. In Oregon, one bill would create a cap-and-trade program. In New York, legislative leaders and the governor reached a deal to enact one of the most ambitious climate mandates in the country that would put the state on track to reach net zero emissions by 2050. That bill recently passed.

“What we’re seeing is these jurisdictions are really serious about” climate change “and it’s a really serious political issue in the constituencies that elect the state and local leadership,” Dewar said. “We think those are very serious targets that are starting to be backed up by policies and regulations, and that the momentum is going to continue to grow.”

Last year saw a flurry of energy policy in state legislatures across the country. Lawmakers considered more than 2,000 energy-related measures nationwide, with more than 400 bills enacted, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Renewable energy and energy efficiency measures dominated the landscape, with nearly 1,000 bills considered last year. Decarbonization, energy storage, subsidies for ailing resources such as nuclear and coal that threaten wholesale market designs, along with natural gas demand, were also considered.

Two years ago, the U.S. Climate Alliance was formed by California, New York and Washington after President Trump announced his intent to withdraw from the Paris Agreement. Twenty-four states are now members aiming to uphold the global pact’s target of cutting emissions by up to 28% below 2005 levels by 2025. Even in extraction states, such as Colorado and New Mexico, Democratic lawmakers are proposing measures to curb emissions or review oil and gas regulations to ensure the climate is better protected.

“It’s likely you’re going to continue to see policies at the state level striving toward lower carbon, cleaner energy,” said the Environmental Defense Fund’s (EDF) Mark Brownstein, senior vice president of energy. EDF has partnered with the oil and gas industry through various initiatives to reduce climate impacts. “It’s what people want, and people are increasingly worried about the consequences if we don’t move in that direction.”

The gulf between what people want and what can be achieved remains wide. But Brownstein’s comments about the likelihood of ongoing political and regulatory pressure were repeatedly echoed by others who don’t expect climate policies to stop anytime soon.

While some renewable proponents have continued to acknowledge the role fossil fuels are likely to play well into the future, a growing body of research suggests that oil, and in particular, natural gas demand, are likely to hit a wall of renewable and alternative competition.

Renewables, batteries and decarbonization could begin to make a dent in gas demand over the next decade. BCG has reviewed the impacts renewables and other market factors might have on natural gas demand.

“You actually see natural gas consumption continuing to grow quite robustly, of course, if you consider liquified natural gas (LNG) exports in that picture into the late 2020s, but then it starts to plateau at that point in time,” Dewar said.

For now, one of the major wild cards in the long-term ascendancy of natural gas is U.S. LNG exports. Project developers are in the midst of launching a second wave of export capacity. In order to secure financing and reach final investment decisions, however, the projects must have customer commitments. That could be challenging given the amount of capacity that’s been proposed.

More than 20 announced projects totaling roughly 35 Bcf/d are looking to catch the second wave of gas exports. Competition is also expected from projects being advanced in other countries and a trade dispute with China, poised to become the world’s largest gas-importing nation, is clouding the outlook for growth. Dewar summed the situation up by saying that far more capacity has been proposed in the U.S. than “the global market can ever bear.”

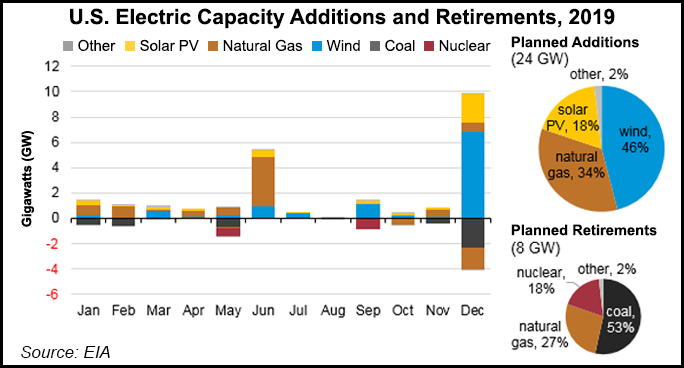

At the same time, the unsubsidized levelized cost of energy (LCOE), a measure used to compare the price of different power sources for wind and solar, has fallen dramatically in the United States. According to BCG, the price per MWh has declined from more than $120 for solar and more than $70 for wind to less than $45 for each. By comparison, the LCOE of combined-cycle gas plants has fallen “only modestly” from near $70/MWh to $56. As a result, BCG said, domestic capacity additions and production growth from wind and solar have exceeded those for natural gas in three of the last four years.

“Solar costs and wind costs have levelized and have been coming down for years now,” BTU Analytics LLC’s Tony Scott, managing director of analytics, told NGI. By 2022, if all of the renewable generation coming to market were met with natural gas, it would represent 12 Bcf/d of demand, according to one BTU assessment.

The problem for gas is particularly acute in the West, Scott noted, where wind and solar resources are robust and have made significant gains. Coal retirements in the region have historically been an opportunity for gas, but facilities have increasingly been replaced by renewables, undermining opportunities for new incremental gas demand.

In the near-term, Drillinginfo concluded recently that some of the gains gas-fired power has made across the country could be cut by wind and solar projects that are slated to come online. If those facilities enter service as scheduled and run at 100% capacity, wind and solar could displace 1.42 Bcf/d of gas demand for power burn over the next five years.

Another upending factor is a marketplace that is increasingly questioning coal and zero-emissions nuclear power plant retirements as states continue to implement or consider subsidies for those resources. Out of market assistance for nuclear and coal could have serious ramifications for gas demand in the power sector.

Electric Power Supply Association CEO John Shelk said during an interview earlier this year that his organization would at this point support carbon pricing in the areas where subsidies are being advanced. The idea appears to be gaining traction in the oil and gas industry not only as a means to fight subsides, but as a way to put fossil fuels on a level playing field with cleaner resources as society demands more renewables.

EPSA’s members, mostly independent power producers, represent the single largest purchasers of gas in the country on any given day. Shelk pointed to the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, a market-based program among states in New England and the Mid-Atlantic, as an example of how well gas comptes in efforts to cap and reduce carbon emissions. “Put a price on carbon, we’ll compete,” Shelk said.

The dynamics have some questioning the long-term role both oil and gas might play.

“Gas and oil are going to have to compete in the future in a way they haven’t had to compete in the past, and I don’t think any of us are smart enough to be able to predict with certainty what that future’s going to look like,” EDF’s Brownstein said.

How energy is produced, delivered and consumed is extraordinarily complex. When the argument over climate change and market designs switches overseas, serious questions remain about the viability of current alternative technologies.

Industrial processes, for example, require huge amounts of energy. Capacity is also expanding to convert natural gas into building blocks for plastics. Both wealthy and developing nations have in the past had difficulties meeting the sorts of targets included in things like the Paris Agreement. If renewables fail to deliver, the world’s thirst for energy won’t be quenched.

To some, energy produced by renewables and stored in batteries, combined with the associated costs in comparison to legacy power sources, won’t be enough to meet global demand. The Manhattan Institute’s Mark Mills, a senior fellow, recently wrote for the conservative think-tank that a gap exists “between aspiration and reality,” physics and policy.

Mills recently authored “The New Energy Economy: An Exercise in Magical Thinking.” For now, he noted, battery storage farms that hold only minutes or hours of power aren’t going to solve the climate crisis. “It’s true that wind turbines, solar cells and batteries will get better, but so too will drilling rigs and combustion engines,” he wrote.

“The idea that ”old’ hydrocarbon technologies are about to be displaced wholesale by a digital-like, clean-tech energy revolution is fantasy,” Mills said. “If we want disruption to the energy status quo, we will need new, foundational discoveries in the sciences.”

There are rumblings of such disruptions. Alternative energy goes well beyond wind and solar. Electric heat pumps and hot water heaters could cut into residential and commercial gas demand. Both grid-scale and residential battery storage are attracting more attention, while power-to-gas energy storage, compressed air energy storage and fourth generation nuclear technology are being advanced and could make serious gains.

There is no doubt that the future for natural gas is long and wide, with various roles to play across the globe. However, as renewables increasingly penetrate the generation stack and policies shift to accommodate more of them, “the role that gas is called upon to play is changing and needs to adapt to supplement and support the reliability of the electric grid,” said Deepa Poduval, an oil and gas industry executive at Black & Veatch.

Poduval authored a study issued earlier this year by the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America (INGAA). In the West, gas has increasingly found a secondary role to renewables as a crucial backup that can power up quickly and fill the void of variable output wind and solar.

In California, for example, renewables typically peak between March and June, while the load peaks in the summer months of July and August. In addition to batteries that can help manage intraday variation, the state still needs a mechanism to manage the seasonal mismatch as battery storage can’t currently handle those duties, Poduval said in May.

INGAA’s study analyzed two scenarios through 2040 in the United States. Under one, a balance of policy initiatives and market economics would find gas-fired capacity additions reaching 35 GW and pushing up demand for power burn by 11.4 Bcf/d. Under the other, a transition heavily driven by policy and intended to accelerate the penetration of renewables would keep natural gas demand roughly flat with today’s level of about 82 Bcf/d.

The role of oil and natural gas in the power sector is just one aspect of the climate issues states are trying to address. Electrification and getting more zero-emissions vehicles on the roads are considered even more complex. The industry argues that natural gas still has an important role to play in the energy transition across various sectors.

Since 1990, gross U.S. greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have increased by 1.3%, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. The largest source of GHGs from humans comes from burning fossil fuels for electricity, heat and transportation.

From year to year, emissions can rise and fall because of changes in the economy, the price of fuel and other factors. Global energy demand last year hit its highest level since 2010, driven in part by extreme weather. The rise in energy consumption led to a 2% increase in carbon emissions or the most robust rate since 2011, according to BP’s annual energy review.

Emissions increases have been curbed for various reasons, including a continued shift from coal to natural gas and increased use of renewables in the electric power sector.

“We continue to drive down methane emissions from the wellhead even as we’re delivering a huge GHG benefit — huge reductions in the electricity sector,” said Western Energy Alliance (WEA) President Kathleen Sgamma. “Efforts by governments to issue fiats on reducing GHG and changing to renewables are all well and good, they haven’t worked well in Europe. Meanwhile, the United States is just getting it done and reducing more emissions through the increased use of natural gas.

“We feel that kind of market force is much better than government fiats and green policies that are set out to 2030 and 2050,” she told NGI.

Hanger called the industry’s stance duplicitous, arguing that its trade groups have supported emissions reductions publicly and fought them behind closed doors. Indeed, groups like the American Petroleum Institute and the Independent Petroleum Association of America have fought the federal government’s past efforts to curb methane emissions from industry sources, filing lawsuits against them and hailing the Trump administration’s efforts to roll back what they see as onerous regulations.

Efforts have also been made by those trade groups and other state organizations like the WEA and Marcellus Shale Coalition to fight regulatory overhauls that would help to cut pollution at the local level or on public lands.

As the push to decarbonize and shift toward alternative energy sources has grown more intense, the industry is rearing its head. Big companies are doubling-down on efforts they’ve long been pursuing to guide the narrative and respond more aggressively to the changing policy environment.

“We definitely see companies stepping up and not only taking action to reduce their own methane emissions, but they are clearly speaking out about the need for government regulation to address methane emissions across the industry, companies like Shell and BP, even ExxonMobil,” the EDF’s Brownstein said.

The majors, along with independent oil and gas companies, have committed to improving environmental performance and reducing methane emissions, participating in a series of partnerships aimed at helping to limit the industry’s climate impact.

Programs are also emerging to certify and track responsibly produced oil and gas, while across the supply chain companies have increasingly promoted corporate responsibility and sustainability issues.

Most recently, BP and Shell joined other Fortune 500 companies in calling on President Trump to impose carbon pricing policy and climate change reforms. In fact, companies like BP have long advocated for carbon taxes.

Big oil companies and other independents have for years used carbon pricing in their operations as GHG emissions are regulated in some regions of the world already. More than 40 governments across the world have implemented some type of carbon price.

Trade groups are doing an about-face as well. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which had not previously embraced the issue of climate change, launched an effort through its Global Energy Institute (GEI) earlier this year to promote bipartisan solutions focused on employing technologies to help reduce environmental impacts instead of regulations.

“I think it’s fair to say that as an industry, it’s been proactive,” GEI’s acting President Christopher Guith told NGI. “And it’s increasingly proactive. Specifically, at least right now, really looking at methane emissions, because that’s really where the rubber meets the road for oil and gas.”

Wherever one falls on the issue of climate change, Guith acknowledged that the industry will have to do more to address it, if not for political or environmental reasons, than for financial.

“Methane is a more potent GHG than carbon dioxide, and if methane is escaping and not being captured, that’s dollar bills floating up into the atmosphere,” he said. “There’s a market incentive to reduce that to zero as close as is technologically possible.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |