NGI Mexico GPI | Infrastructure | NGI All News Access

Mexico’s President, Energy Minister Vow to Revamp Country’s Petrochemical Sector

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and his Energy Minister, Rocío Nahle, have stated their intention to revive the Mexican petrochemical industry.

In a recent visit to Camargo, Chihuahua, close to the U.S. border, López Obrador viewed a Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) fertilizer plant that was closed some 16 years ago. Clearly saddened by the shipwreck of a once-thriving industry, the president swore to revive the plant.

“It will take time and a lot of hard work — a lot of money too — but we’re going to get this plant going again…and the country as well,” López Obrador said.

A few weeks earlier, Nahle, in an academic seminar in the northern state of Zacatecas, recalled her years as a young engineer in a Pemex petrochemical complex in the southern Gulf state of Veracruz.

At the time, China’s petrochemicals industry was in its infancy and learning from Mexico, Nahle told the seminar, “but now it has become a giant, producing textiles, plastics and much more.”

Nahle was referring to what are regarded as the golden years of the Pemex petrochemicals industry that began in the 1980s, which saw a boom in new production facilities.

But the boom was short-lived, replaced by a bust caused by the massive oil find known as Cantarell.

As it began to emerge that Cantarell would be among the world’s largest offshore oil and gas deposits, the field became a fixation for Pemex and the government as a whole. Petrochemicals and other non-core Pemex activities were unceremoniously shoved down the company’s list of priorities.

Reviving the petrochemical industry is “a very admirable goal,” Mercury analyst Arturo Carranza told NGI’s Mexico GPI. “But there are two big stumbling blocks standing in the way.

“One is the absence of the necessary feedstock in the form of natural gas and its derivatives. The other is the need for investment.”

The feedstock issue is complex, but could probably be resolved through additional imports, Carranza says, although the new administration has also been very clear about seeking “energy sovereignty.” The United States is currently shipping 5.7 Bcf/d of natural gas to Mexico via pipeline, a record high.

Carranza said that additionally some form of state support would be required to challenge the very successful petrochemicals producers along the U.S. Gulf Coast buoyed by the shale revolution.

As López Obrador and Nahle aim for a new future for Mexico’s petrochemicals industry, they might learn from the past and its failures.

In the 1980s, “major investors both foreign and national emerged, many of them with operations in and around the port of Altamira on Mexico’s northern Gulf Coast,” Carranza said.

Among the leading private-sector investors were the local unit of Germany’s leading chemicals group BASF Mexicana, S.A. de C.V., and Alpek S.A.B. de C.V., the petrochemicals division of Alfa, S.A.B. de C.V., a Monterrey-based industrial conglomerate.

However, as Pemex production of oil and gas declined from its 2004 peak, both the private sector plants and those of Pemex faced a new problem: the shortage of feedstock.

“The private sector investors were originally attracted by the abundance and relatively low prices of feedstock in Mexico. Now the opposite is true,” Gilberto Ortiz told NGI’s Mexico GPI. Ortiz is the head of the petrochemicals section of the Cámara Nacional de la Industria de la Transformación, or Canacintra, the national industrialists’ association.

“They arrived with the aim of producing petrochemicals but now many have become traders,” he added.

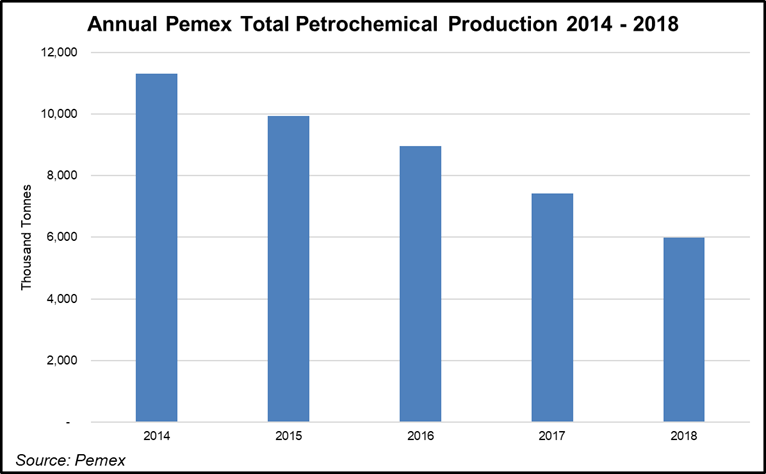

While the private sector companies were able to form a survival strategy, much of the petrochemicals and fertilizer arms of Pemex have slumped.

Pablo Zárate, head of the Pulso Energético think tank, referred in a recent column for El Economista to the undesirable assets of Pemex, including petrochemical plants, but also refineries, processing and logistical centers, that have more costs than they have production.

“By continuing as we have been, assuming that any Pemex asset is inherently good and potentially profitable, is to fall into a trap — a very dangerous trap,” Zárate warned.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |