Shale Daily | NGI All News Access | Regulatory

Hurdles Remain for Trans Mountain Despite Government’s Latest Approval

After escalating into the most extensive native consultations ever on a Canadian project, the Aboriginal rights duel over the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion stopped short of conceding power to any tribe.

“It must be remembered that there is no right of a veto by an Indigenous group in respect of project approval,” said the final summary by Frank Iacobucci, a retired Supreme Court of Canada judge who presided over the canvass.

Iacobucci recited the reminder that native power is limited, while also acknowledging that his orders included recognizing pledges by the Liberal government in Ottawa to adopt the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

“Consultations would be conducted with the aim of securing the ”free, prior and informed consent’ [a UNDRIP rule] of Indigenous groups with respect to project-related impacts on their Aboriginal and treaty rights,” Iacobucci said.

He translated the mandate into practical, cooperative dispute resolution that he calls “the pathway to fair and honorable reconciliation,” the national goal declared by multiple Canadian governments, court precedents and public inquiries.

The second, revised Trans Mountain approval that the federal cabinet announced this week incorporates results that Iacobucci’s nine teams of more than 60 officials from 13 federal departments generated from 402 meetings with 122 native groups.

To obey an August 2018 appellate verdict that overturned the first cabinet approval, Canada “has listened to the concerns expressed by Indigenous groups and has proposed reasonable measures to accommodate those concerns,” Iacobucci said.

“This is indicative of a meaningful, two-way dialogue between the Crown and potentially affected Indigenous groups in accordance with the Crown’s constitutional obligations.”

The second Trans Mountain approval includes stiffened conditions and new government policy commitments requiring native participation in numerous specialties such as marine safety, environmental protection and wildlife preservation.

However, the Trans Mountain chapter in epic Canadian Aboriginal rights contests is not finished yet. Iacobucci’s idea of limited native power is already being challenged.

The Vancouver tribe that led the successful 2018 protest lawsuit, the Tsleil-Waututh Nation, has formally withdrawn consent to the Trans Mountain expansion and vowed “to use all legal tools necessary to ensure that our rights are protected.”

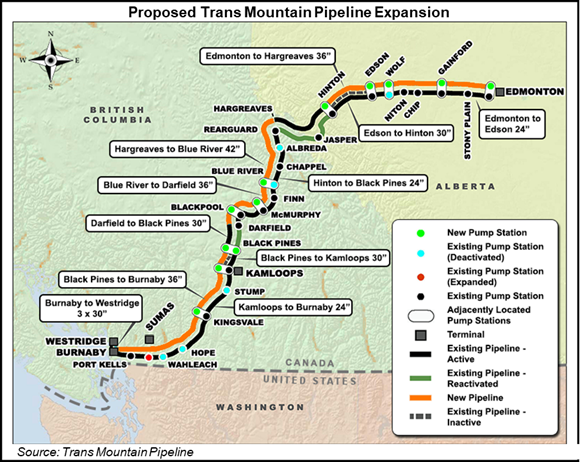

Another group along the 1,147-kilometer (688-mile) pipeline route across Alberta and British Columbia (BC) to a Vancouver tanker dock, the Coldwater Indian Band, is still fighting against expansion construction plans on its southern BC reserve. The pipeline would serve as a conduit for oilsands production.

As the pipeline’s independent regulator, the National Energy Board (NEB) added another reminder of limited power — this time to the government as the project’s sponsor since buying Trans Mountain from Kinder Morgan for C$4.5 billion ($3.4 billion).

In a formal notice to Trans Mountain that included a requirement for distribution to all concerned, the NEB indicated that the regulatory process remains unfinished for the C$9 billion ($6.8 billion) plan to triple the pipeline’s capacity to 890,000 b/d.

“The board reminds Trans Mountain that the issuance of certificates does not automatically reinstate previous board decisions or orders required to commence or resume construction activities,” the notice said.

While federal Finance Minister Bill Morneau predicted Wednesday that work would start this year, the NEB set no dates. The agency only promised to resume proceedings suspended after the federal cabinet’s first project approval was overturned

“In the coming days, the board will issue, for public comment, a proposed approach to resuming the regulatory processes required for the next phases of the project lifecycle, including the detailed route approval process, condition compliance and the board’s consideration of routing and non-routing variance requests,” the NEB said.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |