Regulatory | NGI All News Access

Column: Ixachi and the Swirling Questions Around Natural Gas Market Rules

Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following column as part of a regular series on understanding this process, written by Eduardo Prud’homme. This is the eighth in the series.

Prud’homme was central to the development of Cenagas, the nation’s natural gas pipeline operator, an entity formed in 2015 as part of the energy reform process. He began his career at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), worked for 14 years at the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), rising to be chief economist, and from July 2015 through February served as the ISO Chief Officer for Cenagas, where he oversaw the technical, commercial and economic management of the nascent Natural Gas Integrated System (Sistrangas).

The opinions and positions expressed by Prud’homme do not necessarily reflect the views of NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index.

The week before President Andrés Manuel López Obrador took office, engineers from the exploration and production division at Pemex gave the incoming president some news that buoyed his spirits. They said that a year’s exploration at the Ixachi field in southeast Mexico had uncovered 3P reserves that would make it the largest land discovery in Mexico for 25 years. Not only was the field rich in oil, but it also had a lot of gas: up to 700 MMcf/d.

In the six months since, the field has come to represent an opportunity to achieve “energy sovereignty,” a López Obrador rallying cry during his campaign. Ixachi in the Aztec Nahuatl language means abundance, a perfect term to fuel energy patriotism in the Mexican imagination. It also helps strengthen the president’s message that Mexico is rich in resources, and any production failures at the state oil company are due to the “neo-liberal” policies of previous governments.

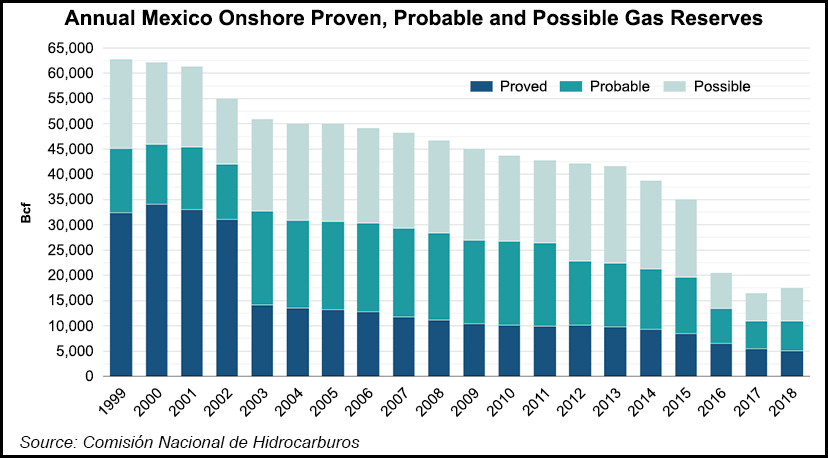

Regardless of how you look at it, the start of production at Ixachi its excellent news. Its volumes and geographic location have the potential to significantly compensate for the decline in domestic natural gas production in Mexico, while at the same time boosting flows into the gas-deprived southeast.

It’s already started. Since January of this year, two exploratory wells at Ixachi gas have pumped gas into the Playuela injection point, where it connects to the 48-inch trunk national pipeline running parallel to the Gulf of Mexico.

But it’s not quite so simple. The pressure differential in the current flow configuration of the national pipeline system Sistrangas means that the gas injected at Playuela is transported to the north, specifically to the Cempoala compression plant. Cempoala has been the point of confluence for gas from the southeast and north, where it has traditionally been redirected to the center of the country.

If the Texas-Tuxpan marine pipeline comes into operation this summer as scheduled, imported gas will be injected into the Sistrangas at the Montegrande interconnection enabling the Cempoala compression station — which is undergoing a reconfiguration — sufficient volume to begin sending gas to the southeast where it is sorely needed.

Playuela gas will then be sent to Juan Díaz Covarrubias. From there, possible destinations will be the Coatzacoalcos area via a 36-inch pipeline, and the Mendoza-Venta de Carpio corridor via a 30-inch pipeline that connects to the center of the country. Commercially, the routes from Playuela are destined mainly for Sistrangas zones 5 and 7. The new operative configuration and the prospective volumes of Ixachi will open access to zone 8, and change the relative volume compositions between destination zones 5 and 7.

Trade routes do not necessarily coincide with physical flows of gas. An unplanned volume increase causes a system capacity change too. The first question to be answered by the new Mexican energy authorities, who have been highly critical of the energy reforms of the previous government, is: should this new production be decoupled from the capacity created? That is, should Pemex sell the gas delivered at the pipeline system injection point, or will it sell it at the extraction points of its customers?

If decoupling is decided on, should the new transport capacity originating in Playuela be assigned? Should an open season happen? Will there be a reassignment of primary or secondary injection points at Playuela?

Do marketers, including Pemex, who buy the gas produced at Ixachi, get priority on the capacity? To whom will Pemex sell the incremental gas produced? Will Pemex’s production be marketed by its own marketing company?

Another question is infrastructure. Although Ixachi creates new capacity originating in Playuela, an increase in volumes simply can’t get everywhere it’s needed. Additionally, if the most optimistic scenarios do bear out, 700 MMcf/d simply is too great a quantity for the current pipeline at Playuela. So, who will pay for the new transportation infrastructure? Who will receive the benefits of such an investment?

There are no easy answers to the questions posed. But with the answers to them, the government of Mexico will tacitly disclose its vision for the natural gas industry.

Interestingly, this same battery of questions is also applicable to the Montegrande interconnection, the reconfiguration of the Cempoala compression station, and even proposed floating storage and regasification units.

In the Montegrande example, the anchor customer and therefore owner of the capacity on the Texas-Tuxpan pipeline is state power company CFE. However, CFE’s contractual rights are confined to the marine pipeline, and they do not have circulation priority through the Sistrangas. The private pipeline is not part of the integrated system and, operated independently, downstream priorities inevitably prevail over upstream ones.

For example, in the international interconnection of Ciudad Camargo at the end of the NET Mexico pipeline system, the way in which Cenagas assigned capacity on the Sistrangas in the first open season opened up competition between marketers by allowing for effective open access across the entire route. This occurred despite the fact that the anchor customer of NET Mex was a subsidiary of Pemex.

The enormous 2.6 Bcf/d capacity of the marine pipeline, the bottleneck created by the interruption of work on the adjoining Tuxpan-Tula pipeline, and the shortage that at times is critical in the southeast of Mexico, open up room for marketers and users who seek more reliable supply.

A possible solution is a segmentation of the incremental capacity so that a priority is given to CFE to partially continue its transit through the Sistrangas. For the remaining capacity, a coordinated or sequential way of allocating capacity resulting from the new flow must be defined. Ideally, such allocation would occur in an impartial manner based on economic and technical merits and that will serve to alleviate CFE’s financial obligations. In any scenario, the questions posed earlier are equally valid.

In the case of Cempoala, the reconfiguration and additional volumes open up previously nonexistent routes. The gas that passed through Cempoala was destined for zones 5 and 7, but it was not feasible to have zones 8 and 9 as destinations. Again, capacity will need to be assigned, and the hope is that the process is transparent, open to all and not biased in favor of state companies.

The backhaul concept could also be used for the routes that previously went from the south to the center of the country and that today will be flow to the south. This way the maximum daily assignments could be respected, but in reverse.

The key point here is that assigning incremental capacity to Pemex and CFE without an open season would be a strong message to the market that the new administration wants to strengthen its champions at the expense of users of the system.

In the end, it’s a debate about whether the energy system favors state companies over users of natural gas, about whether energy sovereignty trumps energy efficiency.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |