Shale Daily | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Breakeven Oil Prices Underscoring Lower 48’s Impact on Market

The oil price needed to profitably drill wells has tracked with prices for long-dated oil futures out to five years, with Lower 48 output appearing to play an outsized role in anchoring prices, according to the Federal Reserve Board of Dallas, aka the Dallas Fed.

Senior research economist Michael D. Plante and associate economist Kunal Patel co-authored a paper about the correlation in prices.

The relevance between price movements “has only grown over the past decade with the emergence of shale oil in the United States,” they noted, as unconventional production has a shorter lead time between drilling and production relative to offshore and conventional exploration projects.

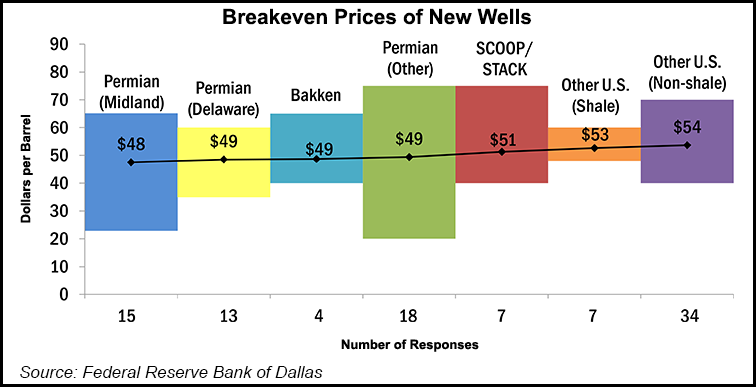

The Dallas Fed Energy Survey, which gauges outlooks for producers and oilfield service executives, every quarter asks respondents what their breakeven oil price is. Over the past year, executives have said the price has fallen by an average of around 4%, or $2.00 to about $50/bbl.

However, the “$50 top-line figure” masks differences in producers and in the rocks they are developing. The Midland and Delaware sub-basins of the Permian Basin “routinely” have lower breakeven prices on average than other locations.

Operators also have variability in their costs. Within the Permian, individual responses in the 1Q2019 survey ranged from $23/bbl to $70. In addition, there often is a wide variation in responses across and within areas.

The Dallas Fed does not define “profitable” in its surveys because a “human element” could factor into the variation. “More important is the reality that some areas are ”sweet’ spots, with lower costs and wells that are more productive,” the researchers said.

More concrete evidence on pricing often is reflected in model-based breakeven prices created by energy consultants, who vary assumptions about drilling costs and production. However, even the model-based breakevens can have variability within and across areas.

For example, one analyst’s breakeven in the West Texas Permian recently ranged from $46/bbl in Loving County to $87 in Reagan County. The broad variance related to the “quality of the rock, with wells in Loving County typically producing at higher rates and lower costs relative to Reagan County.”

There appears to be a “very close and interesting connection between average breakeven prices and the long-dated West Texas Intermediate futures contract. This is true not only for the Dallas Fed Energy Survey, but also for the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s energy survey.”

If the oil market were “perfectly competitive,” long-dated futures prices would equal the marginal costs of supply, ie, the cost of producing one additional unit needed to meet long-run demand.

“In reality, while it is true that most producers in the oil market are price takers — they produce a small amount of oil relative to global supply and their product has minimal differentiation — the oil market is not perfectly competitive,” researchers noted.

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, for example, may add or withhold output because it operates with spare capacity. There also may be political forces that pressure prices. However, there is “ample reason” to suggest the long-dated futures prices will have a close connection with the marginal cost of supply.

Increasing Lower 48 output, likely to be a major source of incremental supply for years, has affected the marginal cost of supply and provides a “plausible link” between the Dallas Fed survey’s breakeven prices and long-dated futures prices. Larger quantities of oil produced in the Lower 48 have proven to be “economical to produce at much lower prices than would have been possible before.”

Oil cost curves over the past decade have moved from being steep to a long, flat line of between $50/bbl and $60, credited to the abundance of Lower 48 resources and lower costs to produce.

“In other words, shale production means there is a much larger amount of supply that can be called into action given a much smaller price increase than in the past,” the researchers said.

Market participants may differ on how much oil is available at a given price, but “they are all aware of the overall trends. These represent strong forces that should keep long-dated futures prices from rising too high or falling too low.”

Given the current market prices, Lower 48 production should continue to expand this year and likely will be a “major driver” over the next five years, according to analysts that include conclusions by the global energy watchdog, the International Energy Agency.

“This does not rule out the possibility of major oil price movements, but it does point to a strong tendency that oil prices will be range-bound in the near future,” Plante and Patel said.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |