Shale Daily | E&P | NGI All News Access

‘Tsunami’ of Crude Output Could See Gulf Coast Bottlenecks Emerge Without New Export Capacity

With U.S. crude oil exports hitting record highs earlier this year, and a tsunami of new production expected in the next couple of years, a massive bottleneck could emerge along the Gulf Coast as early as 2020, according to RBN Energy.

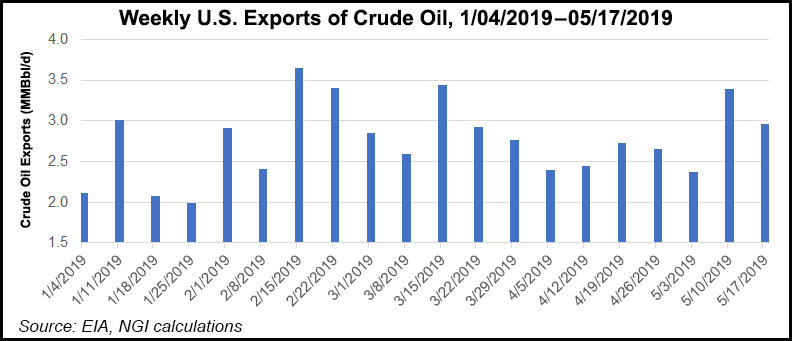

Crude exports reached an all-time high of 3.6 million b/d in February and have averaged just over 2.7 million b/d since the beginning of the year, with exports topping 3 million b/d in multiple weeks, RBN analyst John Zanner said Tuesday in Houston.

“The Gulf Coast is now the premiere market for crude,” Zanner told an audience of 600 or more at xPortCon, RBN’s first conference dedicated to U.S. oil, natural gas and natural gas liquids exports.

During the 16-month period from January 2018 to April, 548 different vessels made a total of 1,402 crude export shipments from Gulf Coast terminals, according to RBN. Of these shipments, 69% involved Aframax tankers, 21% Suezmax and 6% smaller Panamax (less than 500,000 bbl); 3% were loaded directly onto very large crude carriers (VLCC).

The overwhelming majority of shipments on Aframax tankers are because of the common practice of using these and Suez ships to make ship-to-ship (STS) transfers onto VLCCs in offshore Gulf of Mexico loading zones, according to RBN. The firm’s data shows that under half (46%) of the crude export vessels loaded at Gulf Coast ports were for STS transfers destined primarily to Asia.

The rapid export growth since the ban on crude exports was lifted in December 2015 has come as U.S. onshore production has grown exponentially in the last few years, rising to 12.1 million b/d in the most recent weekly data from the Energy Information Administration. That’s up from 8.8 million b/d at the end of 2016. With higher oil prices incentivizing additional drilling activity, a flood of production is set to hit the market in the next few years.

In RBN’s most recent base-case production forecast, which assumes a “fairly conservative” $55/bbl West Texas Intermediate (WTI) price, the firm expects U.S. crude output to increase by 600,000 b/d per year between now and 2024.

“Most of that production will be light crude, and those barrels will want to reach the Gulf Coast,” Zanner said. As the market moves into 2020 and beyond, export capacity along the Gulf Coast will need to increase in lock-step with projected growth to keep up with the wave of crude coming at it. “And that, we think, is where a potentially massive bottleneck could emerge.”

Several midstream companies are considering export terminals capable of sending exports to Asia and Europe, another large international market. One project by Enterprise Products Partners LP would be capable of loading VLCCs with up to 2 million bbl of capacity. Commodity trader Trafigura Group Pte Ltd. is proposing to build a deepwater port in South Texas near Corpus Christi to load supertankers. The Port of Corpus Christi and The Carlyle Group also have a terminal on the drawing board in Corpus, while Enbridge Inc., Kinder Morgan Inc. and Oiltanking GmbH are also partnering in a planned export project. Sentimental Midstream has also thrown its hat in the export ring.

Nevertheless, the permitting process for bringing these projects into fruition “is a nightmare” and the market may only be able to stomach one export terminal, Enterprise CEO Jim Teague said. Supply quality will be key in determining any terminal’s success, he said. “Anybody can build a terminal. It’s supply ability that makes a terminal successful. You have to give producers what they want.”

Enterprise owns the Gulf Coast’s busiest crude export terminal, Enterprise Hydrocarbons Terminal (EHT) in the Houston Ship Channel, which exported about 355,000 b/d from Jan. 1, 2018, to April 25. Enterprise sources the crude delivered to EHT by pipeline from the Permian Basin and Eagle Ford Shale in addition to moving domestic and Canadian supplies from Cushing hub in Oklahoma via the Seaway Pipeline.

Seaway was originally built to ship oil north to Cushing when it entered service in 1976 until 1982, when it became uneconomic to operate. It also shipped natural gas south for a time before oil flows resumed north in 1996. The pipeline was reversed in 2012, sending Cushing crude to the Gulf Coast.

A final investment decision on the VLCC project has not yet been reached, but Teague expressed cautious optimism that it would get built. “I think we’re going to do it. We’ve got $20 million in that application,” he said. “You build something out in the Gulf of Mexico, there’s not a lot of repurposing you can do once that project gets built.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |