Regulatory | NGI All News Access

Column: Where Does Mexico’s Natural Gas Storage Go From Here?

Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following column as part of a regular series on understanding this process, written by Eduardo Prud’homme. This is the sixth in the series.

Prud’homme was central to the development of Cenagas, the nation’s natural gas pipeline operator, an entity formed in 2015 as part of the energy reform process. He began his career at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), worked for 14 years at the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), rising to be chief economist, and from July 2015 through February served as the ISO Chief Officer for Cenagas, where he oversaw the technical, commercial and economic management of the nascent Natural Gas Integrated System (Sistrangas).

The opinions and positions expressed by Prud’homme do not necessarily reflect the views of NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index.

Mexico’s lack of large-scale natural gas storage capacity puts the gas system, and economic activity as a whole, at risk. Cenagas, the independent operator of national pipeline system Sistrangas, only has at its disposal line packing to alleviate daily imbalances.

Even if supply options were diversified, and domestic production increased, the stochastic nature of consumption means gas flow is never secure. Natural gas shortages can lead to failures in the electric power system and have serious impacts on economic activity.

Moreover, the natural decline of Mexico’s hydrocarbon deposits and growing natural gas demand has led over time to the increased need for imported gas via pipelines from the United States and shipments of liquified natural gas (LNG) at Altamira, Manzanillo and Rosarito.

The mere fact that the majority of demand is handled by external agents means geopolitical, climatic or international trade dispute events can impact the availability of gas. Regardless of good trade relationships, having strategic storage also is an insurance policy against the low probability of import problems.

In March 2018, the Energy Ministry (Sener) published its Public Policy on Natural Gas Storage outlining how Mexico would secure strategic reserves to supply natural gas in the case of emergencies. The development of storage infrastructure would contribute not only to the country’s energy security but also to improving operating conditions and strengthening the new natural gas market.

The fact that the seasonality of gas demand in Mexico is opposite to that experienced in the United States opened up interesting opportunities for arbitrage enhanced by storage.

With this in mind, Sener assigned Cenagas several roles to:

The Sener policy was the first attempt at a commercial activity — storage — that had been largely non-existent because of legal restrictions and the lack of market openness before 2014.

Throughout 2018, Sener took concrete steps to implement its policy. This included establishing guidelines regarding the way in which the state would give operator rights to the depleted deposits. The issue is not simple. On the one hand, a deposit will always have traces of hydrocarbons, over which the state has exclusive rights. On the other hand, landowners in Mexico have rights over subsoil.

To resolve this legal contradiction, Sener designed a license scheme, with the participation of the Institute of Administration and Appraisals of National Assets (INDAABIN), the National Hydrocarbons Commission (CNH), the CRE and Cenagas. The idea was that once an exhausted field was declared suitable for storage, CNH would withdraw the field from being considered for auction, and Cenagas would get the green light to tender the field. The winning company would not own the property, but instead provide a storage service while its CRE permit was in effect (terms could be extended for 30 years).

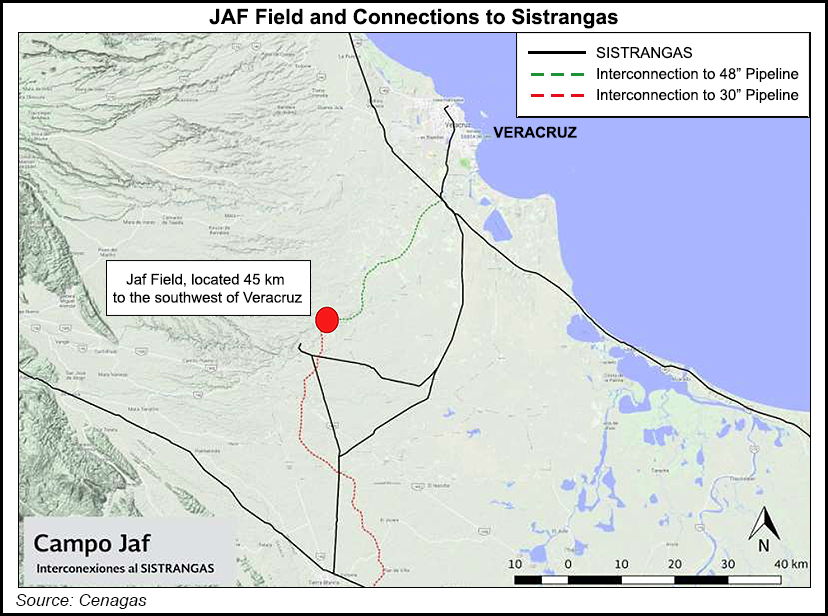

In coordination with the CNH, four depleted fields were declared as economically non-viable for exploration and production, and thus permissible for use as storage sites of natural gas or other hydrocarbons. These fields were Jaf (Veracruz), Brasil (Tamaulipas), Saramako (Tabasco) and Acuyo (Chiapas). Relevant information on these fields can be found, in Spanish, by clicking here.

Cenagas conducted a nomination process to solicit information from international companies with storage experience. The field that won out was Jaf, in part because it was best suited among the four to store about 10 Bcf of working gas. Preliminary bid documents for Jaf were drawn up last September.

That’s where it stands now. The question for the new government of Mexico is whether to continue with the storage policy. And if so, is Jaf the right option for the country’s first storage project?

One key aspect is who pays for it. The previous ministry suggested Sistrangas users, along with shippers on the open access transport systems. The logic was that in an integrated system interconnected with other transport pipelines, improving the conditions of energy security benefits the whole and so everyone should chip in. Sistrangas users would see an additional charge in their Cenagas rates, and Cenagas would receive transfers collected by the other pipes. Cenagas would then pay for the service to the company in charge of the storage field.

The problem with this is that power generation from gas would see an increase in costs, and so in the end storage policy will lead to a slight increase in electricity rates, ceteris paribus, and this runs contrary to the campaign promises of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

However, the new government has also expressed its concern over the security of energy supply. It also seeks to improve Petroleos Mexicanos’ refining and petrochemicals sectors. Achieving this requires improving energy security. Gas storage is crucial to this. If the public storage policy is discarded, it will be very difficult to reduce vulnerability in the national energy system.

One private initiative with important potential is Mirage Energy Corp.’s project at the depleted Brasil field close to the border. It will be interesting to see if the new government grants rights to the field. Storage technically is an activity open to private enterprise under the energy reform.

Regardless, strengthening the gas system must be a priority for Sener. Natural gas storage projects will be supported by different agents of the market as long as the ministry can show that the country as a whole wins, even with higher costs, when energy security is improved.

The new government might also propose ways to mitigate these costs. One option is to decrease storage goals to less than 10 Bcf in a first stage, and/or lower the target of 45 Bcf or move the time horizon beyond 2026. Perhaps other technologies could also provide lower cost solutions.

The new government could consult users and other market participants to define whether it’s better to bet on projects of lower risk and smaller scale. LNG terminals already exist as storage options and salt dome storage facilities are less complex legally than depleted reservoirs. If priority is given to the formation of operational inventories, more thought might be given to strategic storage options through this and future governments.

Perhaps having multiple storage points distributed throughout the country would help legitimize having all shippers pay for storage. Storage at LNG facilities at Altamira could support the Gulf zone, LNG at Manzanillo the BajÃo and the West, along with salt dome facilities in Shalapa (Southeast) and Chihuahua (the North and the Pacific).

Together, orchestrated by Cenagas, this could significantly improve the quality of gas transportation and help to banish the ghost of shortages.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |