Shale Daily | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Regulatory

California Bill Could Erode Plans for New Oil, Gas Drilling

Curtailing or outright banning new oil and natural gas drilling in California is bubbling up as a back-burner public policy issue in the state capital, with proposed legislation that could impose a 2,500-foot setback for drilling.

Assembly Bill 345, which has passed the House Natural Resources Committee, is being championed by environmental groups, but it is a concern for producers. Colorado voters rejected a similar initiative last November.

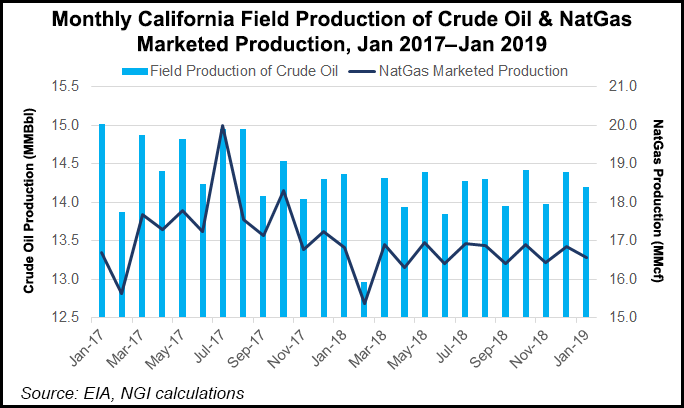

Between 2007 and 2017, California oil production declined 28%, continuing a trend going back to the mid-1980s, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

More than 99% of all drilling permits issued in the state since 2011 have been for existing, historically developed oil and gas fields, the Division of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR) reported.

“It should be noted that based in part on input from environmental advocates, we recently have created or strengthened regulations related to a number of oilfield activities, such as well stimulation, underground gas storage, idle wells and underground injection,” said DOGGR spokesman Don Drysdale.

The Western States Petroleum Association (WSPA) and the California Independent Producers Association (CIPA) have had discussions with Gov. Gavin Newsom and other state officials, but they do not anticipate him supporting an outright ban on new drilling.

WSPA spokesperson Kara Greene told NGI’s Shale Daily that many groups are on record with comments about the proposed setback rule. CIPA CEO Rock Zierman said there is no science supporting the proposal, “considering that California already has the strongest environmental protections in the world.” The proposal is “an end-run to stop production,” and would kill jobs and eliminate tax revenues.

Zierman said continued moves to stop the state’s oil production would be counter-productive, coming “under the strictest regulations on the planet, and that undermines climate goals, which can drive up consumer costs and increase dependence on foreign oil.”

“When you say ‘new’ fossil fuel development here, it is a bit of a misnomer,” Drysdale said. “There are parts of the state where longstanding oil operations are in close proximity to areas that have become heavily urbanized.” It is in these urban settings that residents are seeking setback requirements or an end to new drilling, he said.

A statistic cited before a new well stimulation permit law was enacted estimated that 20% of the drilling in the state involved unconventional drilling, but Drysdale said that given the current ratio of about 600 drilling permits among the state’s 72,000 producing wells, that estimate seemed “exceedingly high.”

“What we can say is that most of the wells being stimulated are new and would not be able to produce” from the targeted formations without unconventional drilling methods, Drysdale said.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |