NGI Mexico GPI | Infrastructure | NGI All News Access

Black Hole in Mexico’s Natural Gas Potential Said to ‘Threaten Nation’s Assets’

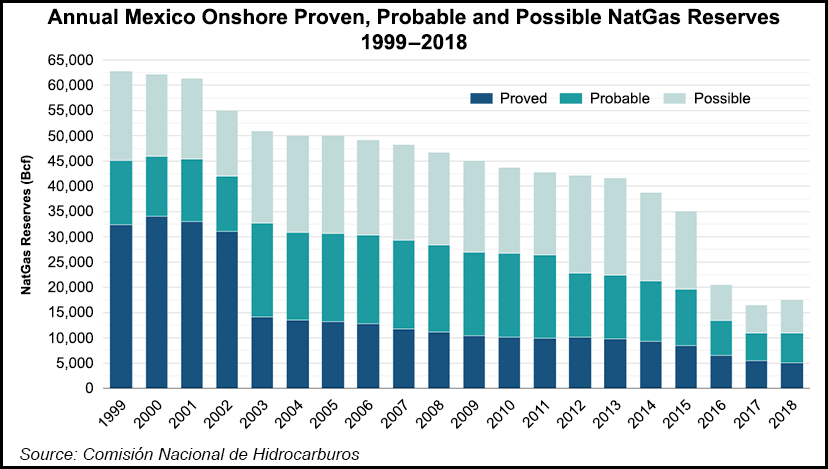

As Mexico’s proven natural gas and crude reserves fall ever rapidly, analysts point to a “black hole” that is tied and bound in the red tape of bureaucracy.

“Half of the prospective reserves have been slashed at the stroke of a pen,” wrote Pablo Zarate in a recent column for the daily El Economista. Zarate, the director of information for Pulso Energetico, a think tank that is supported by Amexhi, the Mexican association of upstream operators and investors, was referring to reserves that would imply the use of hydraulic fracturing (fracking).

Though Energy Minister Rocio Nahle said earlier this year that the government was aiming to permit the technique with strict caveats, since then there has been no clarification on the issue from President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who has frequently opposed fracking, though not necessarily all of its variants.

If fracking is to be banned, Zarate wrote, “it doesn’t take much imagination to understand that this would mean a tragedy in both economic and energy terms, that would condemn our nation to depend on others for gas and petroleum needs.”

The principal “collateral damage” generated by any such ban would be suffered by assets currently reported on the state oil company Petróleos Mexicanos’s (Pemex) balance sheet, Zarate wrote. “If Pemex cannot continue to stimulate wells in the Tampico-Misantla and Burgos basins [those regarded as having the greatest potential, particularly for gas], the value of the great majority of the assets there will simply vanish.”

Zarate added that Pemex “would then have to officially write down the value of the assets and reclassify the reserves in question as ‘contingent’.”

Contingent reserves have zero market value, he underlined.

The United States has shown that prospective reserves can massively add to the value of hydrocarbon assets, Ramses Pech, a partner in the Tabasco-based consultancy Caraiva y Asociados, told NGI’s Mexico GPI.

“The U.S. began in 2008 to develop formations with unconventional resources on the basis of prospective reserves. Now it is heading for 12 million b/d of crude and about more than 85 Bcf/d of gas.

“In Mexico, we have similar basins — the same in a couple of cases — but we don’t invest anything like enough. Worse still, we hardly allow anyone else to invest.”

According to the U.S. Energy Information Agency, Mexico’s unproved wet shale gas technically recoverable resources totaled 543 Tcf in 2013, compared to 567 Tcf in the United States.

Since about early in the current decade, Pech said, the potential of the nation’s shale and other unconventional resources have been recognized, but Pemex had neither the know-how, nor the money, required to exploit them.

“That is why it is so important to hold Rounds 3.2 and 3.3,” Pech said.

Round 3.2 of the series of upstream auctions launched by the 2013 energy reform sought bids for 37 blocks targeting conventional resources, mostly natural gas, in the Burgos Basin in northeastern Mexico. Round 3.3 would have placed on offer nine blocks targeting unconventional gas resources in the Burgos Basin as well, and would have been the first auction for unconventional acreage in Mexico’s history.

But the upstream regulator Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH) confirmed in December that it canceled onshore bid Rounds 3.2 and 3.3, and postponed for six months a farmout tender for stakes in acreage held by Pemex.

The nation’s proven reserves of hydrocarbons stands at 7.9 billion boe, sufficient for the production of 8.5 years, the CNH recently reported.

Mexico’s proven reserves of natural gas at the beginning of 2019 stood at 9.7 Tcf, down 3.7% from a year earlier, the CNH reported. The proven reserves of crude dropped by 6.2% to 6.1 billion bbl.

The CNH said the figures were largely based on those by Pemex and foreign contractors, including Germany’s Deutsche Erdoel; Mexico City-based Hokchi Energy, a subsidiary of Argentina’s Pan American Energy; Italy’s Eni SpA; and Petrolera Cardenas Mora, a Mexican subsidiary of Egypt’s Cheiron Holdings.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |