Markets | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Energy Policy Uncertainty Said Weighing on Mexico Growth Prospects

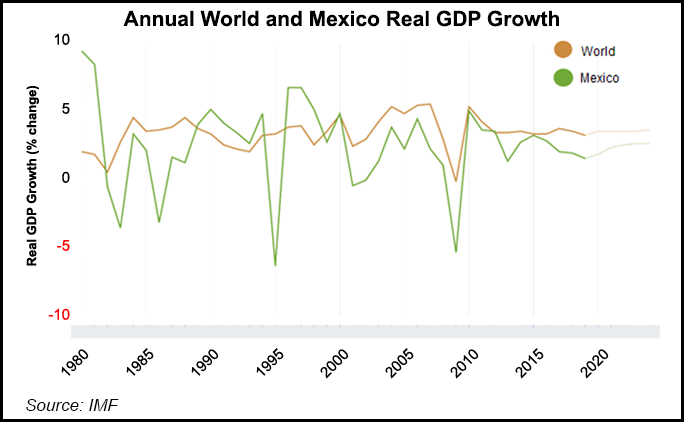

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Mexico unit of Spanish bank BBVA expressed concern this week about the impact of energy policy on Mexico’s economic prospects.

In the latest revision of its World Economic Outlook (WEO), the IMF lowered its 2019 and 2020 Mexico growth forecasts, citing “the incoming administration’s cancellation of a planned airport for the capital and backtracking on energy and education reforms.”

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who took office last December, has long criticized Mexico’s 2013 constitutional energy reform, which liberalized the formerly state-dominated energy sector.

The IMF is now predicting growth of 1.6% in 2019 and 1.9% in 2020, down from January forecasts of 2.1% and 2.2%, respectively.

The predictions for both years were down by nearly a full percentage point from last October, researchers said, explaining that, the changes, “in part, reflect shifts in perceptions about policy direction” in the country.

For the global economy, the IMF is projecting growth to slow to 3.3% in 2019 from 3.6% in 2018, before rising to 3.6% in 2020. The 2019 and 2020 global forecasts are down 0.4 percentage points and 0.1 percentage point, respectively, from January.

Energy policy, specifically as it relates to national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), also figured prominently in a report published Monday by BBVA Bancomer, a division of BBVA, on Mexico’s second quarter economic outlook.

Fitch Ratings in January downgraded Pemex bonds by two notches, one above a junk rating, citing questions over the viability of a planned $8 billion oil refinery in López Obrador’s home state of Tabasco, as well as Pemex’s onerous tax burden, debt load, and labor liability.

In February, López Obrador unveiled a roughly $5.5 billion “rescue” package for Pemex, followed by a March announcement from Deputy Finance Minister Arturo Herrera that the government would tap a rainy day fund for up to $7 billion to help Pemex service debt maturing in 2019.

Although the risk of further downgrades to Pemex’s credit rating has “diminished considerably,” BBVA cited several “worrying signals for the coming years” with regard to the 100% state-owned producer.

The worry signs include Pemex’s increased allocation of capital to the refining segment, which has generated annual losses of around 100 billion pesos ($5.3 billion); postponing from February to October a farm-out tender for operating stakes in seven Pemex-operated onshore areas; a three-year suspension by López Obrador of upstream bid rounds; and “strong pressure” on Pemex “to increase its investment over the coming years due to the relatively large amounts of financial debt that will mature in the 2020-2023 period,” researchers said.

Pemex’s financial debt stood at $106 billion as of end-2018. For these reasons, “it will not only be difficult to reverse the fall in oil production, but also to stabilize it.”

Pemex produced 1.7 million b/d of crude and 3.76 Bcf/d of natural gas in February. While both figures were up slightly from the previous month, they were down from the February 2018 amounts of 1.88 million b/d and 3.97 Bcf/d.

BBVA expects growth to slow to 1.4% in 2019 from 2% in 2018, driven mainly by an expected slowdown in exports from the manufacturing sector.

“The anchor of the economy this year will therefore be internal demand, driven by private consumption, and the gradual recovery of investment toward the second half of the year, in a context of less uncertainty,” the report said.

The IMF and BBVA assessments follow a downward revision in February by Mexico’s central bank Banxico of its 2019 and 2020 growth forecasts, citing a sharper than expected global economic slowdown and uncertainty over domestic policies.

Experts, including Banxico economist Carlo Alcaraz, have also warned that natural gas supply shortages driven by delayed infrastructure projects and declining gas output by Pemex could further inhibit economic growth.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |