Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Understanding LNG’s Complex Role in Mexico’s Natural Gas Market

Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following column as part of a regular series on understanding this process, written by Eduardo Prud’homme. This is the second in the series.

Prud’homme was central to the development of Cenagas, the nation’s natural gas pipeline operator, an entity formed in 2015 as part of the energy reform process. He began his career at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), worked for 14 years at the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), rising to be chief economist, and from July 2015 through February served as the ISO Chief Officer for Cenagas, where he oversaw the technical, commercial and economic management of the nascent Natural Gas Integrated System (Sistrangas).

The opinions and positions expressed by Prud’homme do not necessarily reflect the views of NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index.

Starting with the first liquefied natural gas (LNG) cargo at Altamira, an LNG import facility near Tampico, Tamaulipas, on the northeast coast in August 2006, the supply has taken on a strategic role in Mexico’s energy security.

In an effort to underpin natural gas for power generation in Mexico, state power company Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE) anchored the development of the LNG infrastructure and drew up supply contracts at Altamira. Shortly thereafter, the Manzanillo LNG import terminal on Mexico’s Pacific Coast was built, enabling power plants in the area to switch from fuel oil to natural gas-fueled power generation.

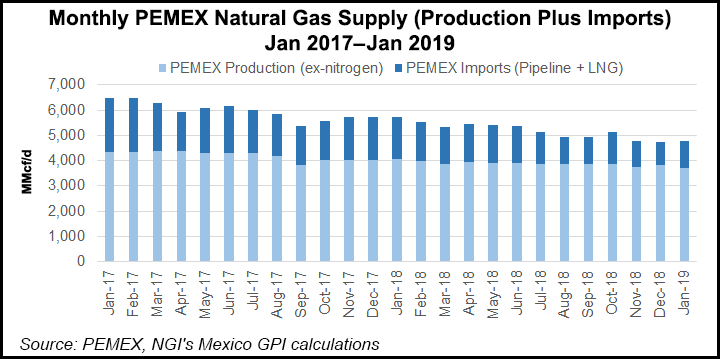

With the Altamira and Manzanillo regasification facilities, LNG imports to both the Gulf and Pacific Coasts of Mexico became an everyday occurrence. By 2011, the dramatic decrease in Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) production caused natural gas shortages across Mexico and a series of “critical alerts” were declared. The only viable solution to the shortage was to use regasified LNG as an auxiliary source to ensure consistent supply across the entire natural gas system.

The Altamira LNG import facility’s location on the Sistrangas network, Mexico’s main pipeline system, also made regas injections a powerful tool to improve system pressure conditions in the event of disturbances in gas production along the Gulf Coast.

However, the price differential between the U.S. pricing hub, Henry Hub, and LNG was significant. Consequently, for the Mexican market there were now two types of gas available: a cheap option produced by Pemex or imported from the United States by pipeline, and another more expensive LNG option. Both were needed to maintain supply.

To rectify the situation, regulators defined a way to allocate the cost of the expensive regasified LNG. A “Balancing Adjustment” was created to distribute the cost of the LNG used when production was insufficient — operated by Pemex, regulated by the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE) and aided by CFE as the largest gas importer into Mexico.

The foundation of the Balancing Adjustment was to distribute the cost of LNG among all natural gas users at an additional charge. Each quarter, the amount of Balancing Adjustment was reviewed by the CRE. The CFE, in addition to making purchases to meet its power-generation demand, now had to consider LNG needed to balance the system for other natural gas end-users.

To ensure commercial viability, Pemex managed the collection and payment system for the additional LNG. However, when national pipeline operator Cenagas was created through the energy reform, Cenagas replaced Pemex as the administrator of the Balancing Adjustment. Between January 2016 and June 2017, Cenagas solicited CFE for the volumes necessary to maintain enough gas flowing in the pipeline network. Cenagas then passed this cost for the LNG balancing on to users through its transportation costs.

However, deregulation of the natural gas market meant that in July 2017 the transportation of gas by pipelines changed to a system that allowed marketers to reserve capacity on the pipeline system, effectively opening access in the Sistrangas network. With this historic change to energy policy in Mexico, the commercialization of gas was now free of price regulation. The central purpose of the new policy was to achieve vertical disintegration in the natural gas market, promoting entry of new marketers and competition that could drive down prices across the country.

In the new system, each user took responsibility in sourcing transport capacity and securing contracts for the supply of natural gas. With a shift to a free market, operative discipline could be enforced, which would lead to adequate balance. Maintaining a policy of socialization of costs was inconsistent and impractical, and so the Balancing Adjustment system was scrapped, but the challenge of covering the cost of LNG balancing reemerged.

There were issues. Who would voluntarily choose the expensive regasified LNG over cheaper options? If the capacity route that was assigned in the open season did not provide access to the supply of economic preference, what was the alternative?

As for the marketers, including Pemex, their commercial strategy would have a tremendous impact on their reputation. Would marketers prefer to reduce the gas on offer to their users? Would they take a risk position to mitigate the effect of the LNG price on their customers? Or would they simply transfer the extra cost of LNG to their customers?

At the same time, three major operational complications conspired to strain the Sistrangas system. Natural gas production in the southeast of Mexico was declining; LNG had limited effects in getting supply to certain regions of the country; and insufficient measurement systems on the pipelines could not effectively identify in a timely manner the shippers who extracted more gas than they injected.

In this context, late 2017 and 2018 heralded in a complex transition period as the market adjusted to balancing a pipeline system with multiple users, insufficient supply and inadequate measurement systems. In the new open market, the costs of regasified LNG were spread across all marketers on the pipeline system, as an additional cost for transportation – and everyone paid the same value per MMBtu, whether they maintained operational discipline around consumption and amounts contracted or not.

End-users, marketers and Cenagas, as the manager of transport capacity of the Sistrangas system, were less than satisfied with delayed billing for expensive LNG balancing, and a new mode of business was required. A set of new natural gas balancing terms and conditions were instituted focusing on Cenagas’ cost recovery for the LNG needed to balance the system.

In the past, marketers shipping natural gas on the Sistrangas system that required LNG balancing could pay back the additional gas they were not contracted to use through injecting the same amount of gas, instead of paying cash for the regasified LNG. This in-kind payback scheme left Cenagas footing the bill for the expensive regasified LNG.

Now, each marketing company will be responsible for the regasified LNG they require. If the company takes more gas from the pipelines than they injected, they will pay for the LNG. However, if they withdraw the same amount of natural gas as they delivered into the system they are not charged a gas balancing fee.

Providing incentive for operational discipline, marketers that are aware that their customers need more natural gas for which they have contracted capacity can buy the regasified LNG directly instead of having to purchase it through CFE.

Meanwhile, there are a number of major strategic infrastructure projects coming online this year, which will alleviate some of the need for LNG in the market. For example, power generation plants that today are served with LNG from Altamira can receive gas from the Sur de Texas-Tuxpan pipeline, slated to come online in the coming months. It is believed that if power generation plants in the Tuxpan area can be served by the marine pipeline, the need to inject regasified LNG from Altamira into the Sistrangas would simply disappear.

In the same vein, if the works on the Cempoala Compression Station conclude before this summer, industrial users in the southeast of the country would have access to imported Texas gas via pipeline.

On the other coast, electricity generation in the port of Manzanillo will be able to source Waha gas from West Texas through a chain of new pipelines, some of which are set to be completed later this year. On the Pacific Coast, assuming the planned pipelines come into operation this year, the quantities of LNG delivered in Manzanillo to be used for balancing gas will certainly be lower than previous years.

With burgeoning production of inexpensive natural gas just north of the border and the entry into full operation of the pipelines tendered by CFE, LNG will likely take on a purely strategic reserve role to be used in times of duress. Nonetheless, meeting growing demand in Mexico with new pipe is not a purely arithmetical issue. There are technical considerations to establishing conditions so that the molecule arrives at a destination with adequate pressure and speed. The geographies of each injection point and each consumption center are also relevant, not just the availability or flexibility to modulate quantities offered or demanded.

Moreover, increased demand from Pemex for natural gas at petrochemical complexes and for injection to boost oil production in the southeast could lead to increased demand that would again require additional LNG.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |