Infrastructure | NGI All News Access

FID on $800 Million Natural Gas Complex in El Salvador Appears Near

A final investment decision (FID) is imminent on an $800 million natural gas project that aims to be the biggest-ever economic and social development initiative in the small Central American nation of El Salvador.

With its neighbors Guatemala and Honduras, El Salvador forms what is known as the Northern Triangle of Central America, arguably the most violent and poverty-ridden corner of the Western Hemisphere. The region has attracted attention in recent months for its “caravans” of migrants heading through Mexico to reach the U.S. border.

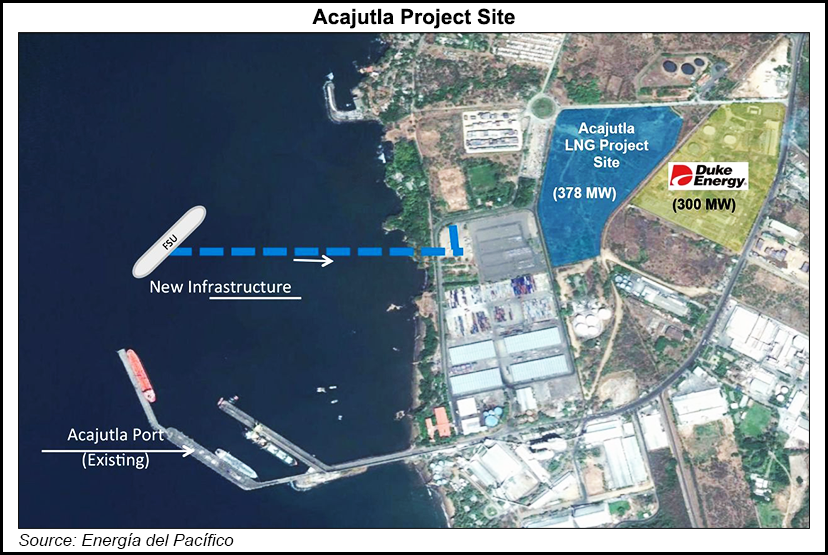

Alejandro Alle, executive director of EnergÃa del PacÃfico, Ltda. de C.V. (EDP), heads the natural gas project. It includes a 378 MW gas-fired power plant, the construction of a floating storage regasification unit, a pipeline to bring the gas to the power plant next to the Pacific Coast port of Acajutla, and a 45-kilometer, 230 kV tension transmission line to an injection point in the national grid.

“The whole project will take about three years to build,” Alle told NGI’s Mexico GPI by telephone from El Salvador.

EDP is 80% controlled by Chicago-based Invenergy LLC while the rest is held by El Salvador’s Quantum Energy S.A. de C.V.. Both companies are clean-fuel enterprises. Invenergy has already developed 21,700 MW of wind, solar, natural gas and storage projects, spanning a swathe of the globe that runs from Scotland to Mexico and Central America, though mainly throughout the United States.

Site work has already begun on the plant, which is being built by Finland’s Wärtsilä. Financial backing will come from the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation, the Washington, D.C.-based Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), Finland’s export agency, Finnvera, and the Germany-based development bank KfW.

Shell was picked in a 2015 tender to be the liquified natural gas (LNG) supplier to the Acajutla terminal and signed a sales-and-purchase accord in April. According to Alle, Acajutla will want about seven cargoes, each of about 500,000 tons of LNG, a year.

The nearest Pacific Basin LNG supplier to Acajutla is Peru, where it would take four or five days to arrive.

Currently, the only natural gas-fired power plant in Central America is the $1 billion Costa Norte plant of the Panama unit of AES Corp., where operations began early last year. Costa Norte is on the Atlantic side of the Panama Canal and is being supplied with LNG by France-based Engie from the Sabine Pass export terminal in the United States.

“The projects in El Salvador will not be competing in any way,” Roberto Dobles, a former Energy minister of Costa Rica told Mexico’s GPI from the Costa Rican capital of San José.

The two countries are, in any case, very different in economic terms, Dobles added. Largely because of the income generated by the Canal, Panama has three times the gross domestic product per head as that of El Salvador.

Alle says that, while the construction of the power plant, its associated facilities and the financial arrangements have to take priority for the moment, EDF hopes to sell LNG to locations up and down the Pacific Coast of the Northern Triangle. “That would certainly make sense,” said Dobles, assuming that the price is competitive with the “bunker fuel” that supplies most of industry in the region.

El Salvador, whose population of some 6.5 million is similar to that of the U.S. state of Missouri, has made efforts to diversify its energy matrix by breaking the dependence on imported oil, which still accounts for about 40% of consumption. Hydroelectricity has a 30% share while biomass and geothermal have 25%. Solar and wind power have made relatively little headway so far, but there are big plans for both.

Strains with the United States’ government have certainly emerged in recent months over the migration crisis and also by a Salvadoran government decision to break long-standing diplomatic relations with Taiwan and embrace Beijing.

But Dobles flatly rejects the view that the EDP project could be at risk if further tensions were to arise. “It’s a project that’s been underway for about six years or more, and it’s backed by the World Bank and OPIC. That’s all very solid,” he said.

Last weekend, Nayib Bukele was elected president of El Salvador. At the age of 37 he broke the duopoly of the parties of the former enemies of the civil war that ended in 1992. With a stagnant economy and no end to criminal violence, voters clearly backed an “outsider”.

The problem, Dobles said, is that Bukele’s coalition has only 11 seats in the nation’s Congress, while the political old guard of left and right have 60. “He’s something of a social media star,” added Dobles. “He needs to be.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |