E&P | Infrastructure | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Appalachian E&Ps Cutting Back Amid Flush Natural Gas Market, Shifting Expectations

The tenacious natural gas production growth that has characterized the Appalachian Basin over the last decade finally appears to be slowing as an epic pipeline buildout nears its conclusion, demand ebbs and operators realign their visions for the future.

As 2019 gets into full swing, it promises to be another year of natural gas oversupply. And while demand looks positive with liquefied natural gas (LNG) export capacity ramping-up, gas-fired power increasing and Mexican exports growing, it won’t be enough anytime soon to stoke significant production spikes in the nation’s largest gas-producing region. Volumes are still expected to grow, albeit at a more modest pace than they have in the past.

“The way I think about it is how much are [producers] going to grow,” said analyst Justin Shiver of East Daley Capital Advisors Inc. in an interview with NGI. “It’s not are they’re going to decline, or stay flat, it’s more of a question of how much are they going to grow production.”

Pipeline Boom Ending

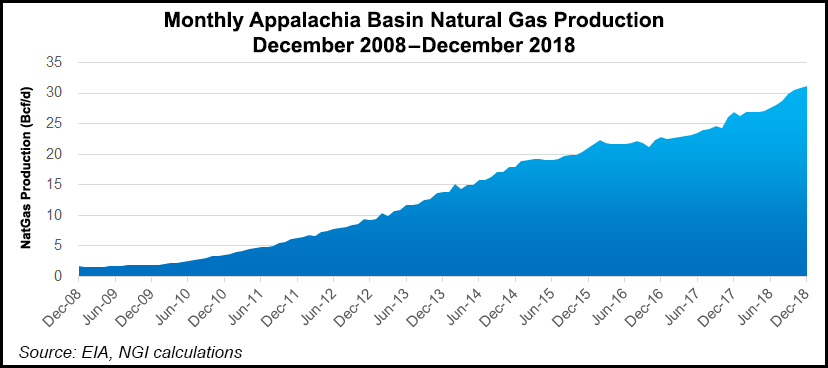

Over the last 10 years, Appalachian gas production has captivated the market. The basin was transformed from a has-been marginal field to one that now accounts for more than one-quarter of all gas produced in the United States. By 2015, production from the Marcellus and Utica shales reached about 20 Bcf/d. It continued growing as a frenzied stretch of pipeline construction raged on.

Over the last 15 months, the buildout culminated in roughly 10 Bcf/d of Northeast takeaway capacity coming online. Major projects such as the Rover Pipeline, Atlantic Sunrise expansion and Nexus Gas Transmission system entered service. The new conduits helped to unleash another 7 Bcf/d of production in that time, pushing Appalachian volumes to their current level of 31 Bcf/d, according to a recent analysis by Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. LLC.

The only other major greenfield pipeline projects slated to come online in Appalachia between this year and next are the Mountain Valley Pipeline and the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. The costs for those projects have soared amidst regulatory and legal challenges that have thrust their eventual completions into question.

“Overall, we believe there will be slight growth in the Marcellus/Utica this year, but that we will remain well below capacity out, suggesting differentials should stay narrow and Marcellus/Utica players should enjoy high realizations,” the Bernstein analysts said.

All the new pipelines have finally lifted local prices for Appalachian operators, many of which have no other levers to pull as pure-play producers. Firm transportation commitments, gathering and processing contracts and incremental demand are also expected to keep production rising modestly this year, analysts said. But they agreed growth rates won’t be as robust.

Cutting Back

Shiver noted that as recently as mid-2018, many of Appalachia’s leading operators were on average calling for annual production growth of about 17% in the years ahead. Reality has started to sink in, however, and those visions are crashing back to earth.

“That amount of growth is unsustainable. You’ve seen a lot of those guys already pull back on the guidance, and I think you’re going to see more of that moving forward, definitely,” Shiver said. “I think it’s still going to grow. But you can’t grow at a 15% or 20% [rate] when the market is already reaching a point of oversupply.”

Indeed, in a recent interview with NGI, EQT Corp. CEO Robert McNally, who runs the nation’s largest gas producer, said it would be “foolish” for his company to grow at those kinds of rates as it’s done in the past. EQT announced a plan earlier in January to cut spending, keep production flat this year, and grow longer-term volumes in the single-digits.

“It’s time for the companies to start acting like grown-up companies, generating returns for shareholders and not just consuming capital, not growth just for growth’s sake,” McNally said of his peers. “I’m pleased with the direction we’re headed, and I think that many in the industry are following that same path.”

Other Appalachian operators such as Antero Resources Corp., Gulfport Energy Corp. and Chesapeake Energy Corp. have announced that they’ll cut spending and activity levels this year. They’ve joined peers in other basins that have reacted to market swings and the free falling oil prices of late last year by reining in activity. Leading oilfield service companies Halliburton Co. and Schlumberger Ltd. have already warned as earnings season gets underway that skittish exploration and production companies may delay a broader recovery.

Meanwhile, fickle investors in search of higher returns have kept the pressure on executive management teams across the country. Antero, Gulfport and EQT, for example, have all faced restive shareholders demanding more value

“We continue to see this importance in the market of returning capital to investors with share buybacks, dividends, paying off debt,” said BTU Analytics LLC’s Matt Hoza, who oversees energy analysis for the firm. “There’s this emphasis on capital discipline, which can eat into your capex budget or your drilling and completion budget.”

While analysts still see room for growth, producers are slowly easing off the pedal as the market becomes saturated with natural gas.

“In our opinion, we haven’t seen the structural demand growth to keep pace with this production growth that we have right now,” Hoza told NGI. “The biggest driver that we’ve seen on the demand side is LNG export growth.”

Five LNG export facilities are expected to ramp up this year. NGI estimates the new facilities will increase nameplate send-out capacity to more than 9.5 Bcf/d from the roughly 4.0 Bcf/d currently in service. Even still, Hoza and Shiver both agreed that the second wave of LNG facilities expected to be built and brought online over the next five years are what’s really needed to cut into the wall of natural gas.

Power burn is also expected to grow. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) recently said gas and renewables would again account for most of the country’s power generation capacity additions in 2019. But Hoza said that at a certain point gas-on-gas demand — or more efficient plants that generate electricity with less gas — erode some of those gains.

“From a demand perspective, in our view LNG and exports to Mexico are going to be the biggest demand drivers going forward over the next five years, with LNG really taking the top spot.”

Weak Outlook

These days, however, Appalachia has more to deal with. Associated gas production in the booming Permian Basin is expected to continue rising, while resurgent volumes from the Rockies, in places like the Powder River Basin, and a recharged Haynesville Shale in East Texas are anticipated to eat away at the Northeast’s market share.

The outlook for gas prices also looks weaker, especially after the volatility of winter and the demand that comes with it fades. The EIA recently lowered its 2019 gas price forecast. Henry Hub prices are expected to average just $2.89/MMBtu, or 26 cents below the 2018 average of $3.15/MMBtu, according to the latest Short-Term Energy Outlook (STEO).

The STEO shows year/year production increasing by about 7 Bcf/d nationwide to 90.2 Bcf/d this year and by just 2 Bcf/d between 2019 and 2020. Compare that to growth of about 8.5 Bcf/d from 2017 to 2018. One reference case in the EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook shows gas production growth slowing to less than 1% per year after 2020.

“Northeast production is going to feel it too,” Hoza said. BTU currently forecasts about 1 Bcf/d of growth in Appalachia between December 2018 and December 2019.

As dry gas production slows, wet gas volumes in Appalachia could continue increasing as they did last year when stronger oil prices incentivized a deeper focus on natural gas liquids (NGL). The shift came after operators spent years developing drier acreage following the 2014 commodities downturn.

While oil prices fell precipitously as 2018 came to an end, they’ve since clawed their way back and the crude outlook has improved. The Mariner East 2 liquids pipeline also recently entered partial service in Appalachia and hedge books have yet to fall off, analysts noted.

A case in point is Antero, one of the nation’s largest NGL producers. The company was emboldened by better prices last year to direct operations entirely to liquids-rich locations in the Marcellus of West Virginia and scrapped plans for drier acreage in Ohio. The company is sticking with that plan this year and has forecasted a 26% increase in liquids production.

In any event, as the Northeast pipeline buildout has slowly wound down, operators have become more familiar with their unconventional targets and as the industry focuses on downstream opportunities, some of the buzz seems lost as other plays grab headlines.

“Appalachia has been left out a little bit,” Shiver said. “I don’t know if it’s warranted. I think there’s just less [mergers and acquisitions], less new projects being proposed in the area — you had a giant wave of projects planned that came to fruition. And now it’s this play that everyone sees as debottlenecked. Everything’s good; It’ll take them a couple years to fill this capacity.”

The basin is simply more established, Shiver added. But Thomas Murphy, director of the Marcellus Center for Outreach and Research at Pennsylvania State University, said that shouldn’t deceive anyone as industry activity in the region is still strong heading into 2019.

“The reality is, there has been greatly enhanced efficiency in the process, fewer rigs does not necessarily equate to less productivity,” he said. “We continue to see year-on-year increases in the volume of natural gas that’s being produced in the Marcellus and Utica.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |