Regulatory | Mexico | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

López Obrador Likely to Bring Changes to Mexico Natural Gas Market

Although Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador has said relatively little about natural gas policy, he has made clear his opposition to the 2013 constitutional energy reform of his predecessor, Enrique Peña Nieto.

The reform, which broke up the vertical monopolies held by national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) and Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE) over the hydrocarbon and power segments, respectively, laid the groundwork for an open and competitive natural gas market.

While important progress has been made, Mexico’s natural gas market remains in an incipient stage. Some of the signposts to watch for in the coming months to gauge the progress of the market’s continued evolution under López Obrador include:

In 2017, Mexico’s Comisión Reguladora de EnergÃa (CRE) began publishing the IPGN monthly natural gas price index, a compilation of prices reported by natural gas marketers in the country.

The IPGN was intended as a temporary measure until the market attained enough liquidity and pricing transparency for third-party indices, and intra-day and day-ahead markets, to emerge.

As part of the effort to attain these goals, CFE — Mexico’s largest consumer and shipper of gas — is developing a real-time electronic trading platform called Activgas.

“ActivGas will stream live market prices on which users can trade, removing barriers and driving transparency and access to all,” according to a November presentation by Eugenio Herrera, the chief legal officer for CFEnergÃa, the gas trading arm of CFE.

“Through a dashboard, the market participants (i.e. the counterparties of CFEnergÃa) will know at all times (subject to market hours) at what price CFEnergÃa is willing to buy and sell natural gas, in different zones (i.e. in 7 out of 8 zones in which the country is divided for the natural gas market) or points at the border,” thereby setting the stage for a forward market.

Both López Obrador and CFE’s new CEO, Manuel Bartlett, have expressed opposition to the idea of CFE purchasing gas or electricity from non-state actors, throwing into question whether ActivGas will see the light of day.

Arguably the largest barrier to entry for private sector shippers in Mexico’s gas market is a lack of access to pipeline capacity, according to market participants.

Whether Cenagas continues to hold open seasons for pipeline capacity within Mexico, as well as auctions for cross-border pipeline capacity from the United States into Mexico, will be a strong indicator of the government’s stance toward a liberalized natural gas market.

Mexico’s Centro Nacional de Control de Gas Natural (Cenagas) in August published preliminary bidding terms for a tender that would award a service contract to build and operate a 10 Bcf underground natural gas storage facility at the depleted Jaf field in Veracruz state.

The tender is part of a larger goal by Cenagas for Mexico to add 45 Bcf of underground storage capacity, or five days’ worth of supply, by 2026.

“This policy, ambitious for Mexico, is in line with averages around the world,” Mexico City-based think tank Pulso Energético said in a September note, citing that many developed natural gas markets have upwards of 30 days’ worth of storage capacity.

The new administration has not indicated whether it will proceed with the tender.

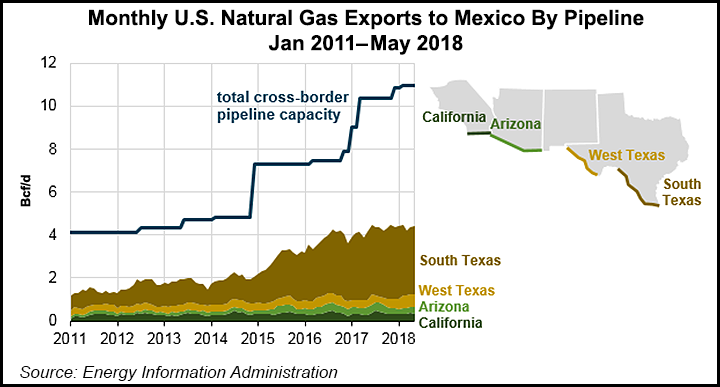

Natural gas production reported by national oil company Pemex, excluding nitrogen, averaged 3.76 Bcf/d in November 2018, down from 4.02 Bcf/d in the same month a year ago, and from a peak of 6.52 Bcf/d reached in 2009. As a result of the output decline, and of rising demand from the power sector, pipeline imports from the United States soared to record highs in 2018, and are expected to continue ramping up as new pipeline infrastructure comes online.

Pemex CEO Octavio Romero Oropeza has pledged a 50% increase in natural gas production to 5.7 Bcf/d by 2024, to be driven mainly by associated gas from shallow-water oilfields in Mexico’s Sureste basin that were allocated to the state oil company under the previous government’s 2013 constitutional energy reform.

Some critics have argued that the output goal is unrealistic, and that the government’s plan to “rescue” Pemex does not give sufficient priority to non-associated unconventional gas in basins such as the Burgos, Sabinas/Burro-Picachos, and Tampico-Misantla. President López Obrador also opposes hydraulic fracturing, and cancelled bid rounds 3.2 and 3.3, which had sought to award onshore gas blocks, mostly in the northern border state of Tamaulipas.

Although Mexico has added 4,639 kilometers (2,882 miles) of natural gas pipelines since 2012, several important projects still face delays, mostly due to local opposition. These include the final two stages of Fermaca’s colloquially named “Wahalajara” system, which will allow gas from the Waha hub in West Texas to reach the city of Guadalajara in Jalisco state; TransCanada’s Tuxpan-Tula and Tula-Villa de Reyes pipelines, which will allow the undersea Sur de Texas-Tuxpan pipeline to operate at full capacity; and Carso Energy’s 472 MMcf/d Samalayuca-Sasabe pipeline, which will transport gas from Waha to Northwestern Mexico.

These projects, along with the reconfiguration of the Cempoala compressor station in Veracruz state, will allow Mexico to substitute costly LNG imports with much cheaper pipeline gas from West and South Texas. They are also expected to help ease the acute gas supply shortages that have plagued southeastern Mexico in recent months.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |