NGI Mexico GPI | Markets | NGI All News Access

NGI’s Top Five Mexico Natural Gas Trends in 2018

2018 was a momentous year for Mexico’s energy sector, and could very well define hydrocarbon production and distribution in the country for the foreseeable future. Although there is much to pick from, NGI’s Mexico GPI has narrowed down the major Mexican natural gas trends for 2018 to five:

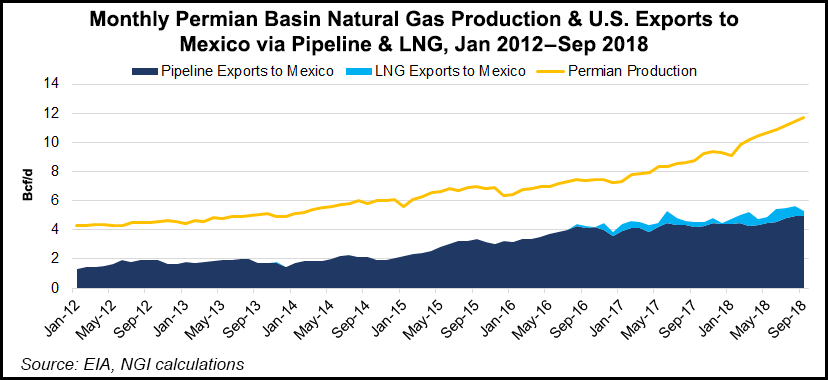

Natural gas imports from the U.S. kept growing in Mexico throughout 2018, reaching record levels in August. Pipeline imports averaged 5.1 Bcf/d during that month, the Energy Information Agency (EIA) said, up from 4.5 Bcf/d in August 2017. Piped gas accounted for 60% of those imports, up from 58% in the year-ago month, with liquefied natural gas (LNG) making up the remainder.

“Dry natural gas production in Mexico has fallen 38% since 2012 because of declining reserves, a low price environment, and limited exploration and production of new wells,” EIA said, citing that Mexico’s dry gas output fell 7% year-on-year in October to average 2.4 Bcf/d. The October figure was down 21% from two years ago, when production averaged 3.0 Bcf/d.

In 2010, Mexico imported only 0.8 Bcf/d from the U.S., according to analysts at Raymond James. Raymond James sees this figure jump to 6.2 Bcf/d in 2020.

“I’ve seen estimates all over the board,” said NGI’s Patrick Rau, director of Strategy & Research. “Some are calling for peak exports to reach 6.4 Bcf/d by 2020, others 7.6 Bcf/d by 2023. It all depends on by when delayed pipeline projects come on in Mexico, and when domestic Mexican natural gas production starts to increase, which would crowd out some of those U.S. exports.”

Soaring oil and associated gas production in the Permian Basin in Texas overwhelmed takeaway capacity and pressured prices in the region in 2018, reaching unprecedented territory in November when some day-ahead deals traded below zero. It marked the first time NGI has ever recorded negative spot natural gas prices in the United States.

The need to get the gas to market is urgent, and Mexico benefits from cheap and plentiful gas.

New pipelines are crucial to getting this gas into the Mexican market. Significant cross-border transport infrastructure was brought online in 2018, including Enbridge Inc.’s Valley Crossing pipeline, Howard Energy Partners and Grupo Clisa’s Nueva Era pipeline system, Fermaca’s El Encino-La Laguna pipeline, and TransCanada’s El Encino-Topolobampo pipeline.

The Sur de Texas-Tuxpan marine pipeline is scheduled to enter service in early 2019, according to developers TransCanada and Infraestructura Energética Nova (IEnova). However, the undersea pipe will only operate at 60% of its 2.6 Bcf/d capacity over the near-term, due to the indefinite suspension of work on sections of TransCanada’s Tuxpan-Tula and Tula-Villa de Reyes pipelines extending into central Mexico. Also facing delays is Carso Energy’s 472 MMcf/d Samalayuca-Sasabe pipeline, which will transport gas from Waha to Northwestern Mexico.

Of welcome news to natural gas trade was the tentative signing at the end of November of the United States-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) trade agreement. The agreement, which still requires approval by the U.S. Congress, allows for tax-free transport of raw and refined products across borders.

In late August, 2018, Mexico said it would tender its first storage project at a depleted natural gas reservoir in Veracruz state. The Centro Nacional de Control del Gas Natural (Cenagas) published the preliminary bid documents for the tender, which will offer a service contract to build and operate a 10 Bcf storage facility at the Jaf field in central Mexico. To date, a timeline for the auction has yet to be established.

Mexico’s natural gas storage policy, published in early 2018, mandates that Cenagas develop 45 Bcf of strategic inventories on Mexico’s largest pipeline system, the Sistrangas. The Jaf tender is the first of these strategic projects, which would be reserved for supply emergencies.

Mexico currently lacks underground gas storage facilities, relying instead on tankers at LNG terminals for short-term balancing. In August of 2018, New Fortress Energy (NFE) won a tender to develop, build and operate Mexico’s fourth LNG import facility in the port of Pichilingue in the state of Baja California Sur.

Since being sworn into office on Dec. 1, López Obrador has cancelled oil and gas rounds for three years; pledged to build a new $8 billion refinery as part of a plan to stop fuel imports from the United States; railed against the energy reform in general; given state oil firm Petróleos Mexicanos additional capital while slashing the budget of regulators that oversee the sector; and proclaimed that the country will boost oil production by 40% and natural gas production by 50% in his six years in office in a bid for energy self sufficiency.

“This repeated mantra on energy independence, it may sound very good and hit all the right nationalistic notes, but it really isn’t realistic in the short term,” Duncan Wood of the Wilson Center told NGI’s Mexico GPI. “Mexico is dependent on imported fuels and natural gas, and it will take a long time to change this. And on natural gas — without fracking, which López Obrador has said will not occur — I don’t see it possible.”

One change that might occur is lower natural gas needs for power generation. Mexican combined-cycle gas turbine (CCGT) projects were expected to add 2.3 GW of generation capacity in 2018, a further 3.6 GW in 2019, and a total of 28.1 GW over the next 15 years, the Energy Ministry (Sener) said in its 2018-2032 Prodesen power sector outlook. But the new president has called for a change in electric power plans.

“There is no way that Mexico can substitute out U.S. natural gas in the short term,” Wood said. “But I do expect we will at least see some switching over from gas to fuel oil in power generation. He [López Obrador] even wants to bring back some old capacity and use fuel oil in it. So he might have the opportunity to reduce some current demand for U.S. natural gas.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |