Shale Daily | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI Mexico GPI | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Mexico’s Energy Reform Still Showing Signs of Life

Mark Twain’s famous quip, that “The report of my death was an exaggeration,” could well apply to Mexico’s energy reform.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador is believed by many to have buried the reform with his description of it as a “vile ruse” schemed up by the “neo-liberals” who have ruled the Mexican economy for more than two decades. However, the reform, for now, is very much alive.

“The legal framework of the energy reform has been untouched,” consultant Guillermo Suarez, of Mexico City-based GSF Energy Consultants told NGI’s Shale Daily. “The new government has offered no alternative.”

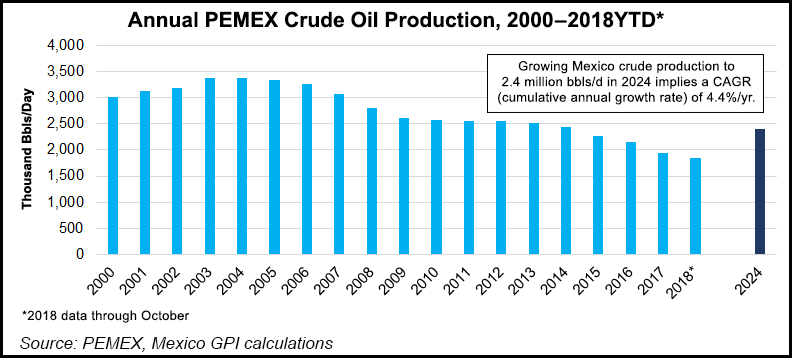

Even though upstream auctions have been put on hold for three years, the government can readily resume them. The new government has ambitious targets to reach 2.4 million b/d of oil production by 2024, from 1.8 million b/d today. There also are plans to boost natural gas production by 50% in the same period to reach 5.7 Bcf/d by the end of 2024.

López Obrador has said he will respect all existing contracts, that there will be no nationalizations and that he would refer any disputes be taken before international tribunals. There is simply too much private sector investment already committed for any drastic change to take place, according to several analysts and industry sources.

Although the president recently announced deep budget cuts for government entities that oversee the energy industry, the regulators remain independent with their roles intact. Legislation introduced earlier this year by López Obrador’s Morena political coalition, which sought to fold the Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH) and Comisión Reguladora de EnergÃa (CRE) into energy ministry Sener, was withdrawn after an outcry from prominent industry voices.

“There’s no question of canceling existing contracts,” said editor David Shields of EnergÃa a debate magazine. “But that could come later, perhaps in three years or so if production from the [energy reform] contracts fails to reach expectations.”

The fact is the reform has been easy to criticize, and López Obrador’s opposition to it has gained the president political clout. While the reform opened up the energy sector to international oil and gas companies, corruption was rampant at state oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) under the previous government of Enrique Peña Nieto.

“I’ve had several conversations with government officials and contractors lately and they all said this was the worst corruption they had ever seen in Mexico. Shameful,” tweeted David Luhnow, Latin America editor for The Wall Street Journal.

Meanwhile, the reform wasn’t given time to be successful. “The Mexican political system, with its six-year, no re-election presidencies is a barrier to social and economic progress,” Mexico Energy Intelligence’s George Baker told NGI’s Shale Daily.

Finally, the Peña Nieto government was too ambitious in its production aims. The country’s current oil output is 40% below the 3 million b/d promised for 2018 by Peña Nieto three years ago. López Obrador blames the energy reform for these declines in oil and gas production, although most analysts agree that in order to reverse falling production he will need the help of the private sector.

“I think that as the realization dawns on him [López Obrador] that there are very limited resources and that Pemex has very limited capacity, he’s going to recognize that the private sector is an essential partner,” the Wilson Center’s Duncan Wood told NGI’s Shale Daily earlier this year.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |