Utica Shale | Marcellus | NGI All News Access

ACP, MVP Confronting Latest Legal Challenges

More legal fronts opened last week for the Atlantic Coast (ACP) and Mountain Valley (MVP) pipelines in what’s become a saga for the Appalachian shale gas takeaway projects that continue to face rising costs and delays.

ACP has again stopped work after the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit on Friday stayed the implementation of key federal authorizations that have already been reworked in response to ceaseless legal challenges by environmental groups led by the Sierra Club. Meanwhile, Virginia officials filed a lawsuit against MVP for alleged environmental violations that occurred during construction in various counties in recent months.

The Fourth Circuit stopped the implementation of ACP’s re-issued biological opinion and modified incidental take statement (ITS). The move could further delay full service on the system beyond the mid-2020 guidance, according to analysts at ClearView Energy Partners LLC.

Work on the pipeline was temporarily stopped earlier this year when the Fourth Circuit first vacated the ITS issued under the Endangered Species Act. The permit is required for activities that could harm threatened wildlife.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) later revised the biological opinion and modified the ITS in response. But the Sierra Club argued that the agency pushed the process too quickly for political reasons, compounding risks for the Indiana Bat, the Clubshell Mussel, the Rusty Patched Bumble Bee and the Madison Cave Isopod. The court agreed to stay the reissued authorizations pending appeal.

“We believe FWS thoroughly addressed the issues raised by the court and the petitioners in this case when it reauthorized the project’s biological opinion and ITS in September,” ACP spokesman Aaron Ruby said. “In developing this project over the last four years, we have taken extraordinary care to protect the sensitive species at issue in this case. We will vigorously defend the agency’s reauthorizations and the measures we’ve taken to protect the species in oral arguments before the court early next year.”

Ruby said the company has temporarily halted construction until it receives clarification from the court on its request to narrow the order to areas where the species are located, which could prevent work from stopping for a prolonged period over the entire route.

“The issues in this case involve a much narrower scope of the project — only four species and roughly 100 miles in West Virginia and Virginia. We will have more clarity on the scope of the court’s stay and its impact on the project when the court responds to our motion,” he said.

Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring and the state Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) filed the state’s lawsuit against MVP. It alleges that MVP violated environmental laws and the Section 401 Water Quality Certification issued by the state under the federal Clean Water Act. Seeking the “maximum allowable civil penalties” and a court order to force the project into compliance, the state noted that many of the violations occurred during heavy rainfall this year.

Responding to public complaints, DEQ inspectors identified the violations from May through October in Craig, Franklin, Giles, Montgomery and Roanoke counties. More than 300 violations, mainly related to improper erosion control and stormwater management, were discovered.

Parts of the Appalachian Basin have seen heavy rainfall this year, and land issues have been widely documented as a result. At one point in June, the DEQ and MVP coordinated to temporarily stop construction so soil erosion and sediment control issues that led to standard notices of violation could be addressed.

“The unusually wet conditions and periods of record rainfall this year in Virginia have presented construction challenges, and the MVP project team has worked diligently to ensure appropriate soil erosion and sediment controls were implemented and restored where necessary along the route,” MVP project spokeswoman Natalie Cox said.

The lawsuit was filed in the Circuit Court of Henrico County. It alleges 10 violations, including unpermitted discharges, failure to maintain and repair erosion control structures and failure to maintain access roads.

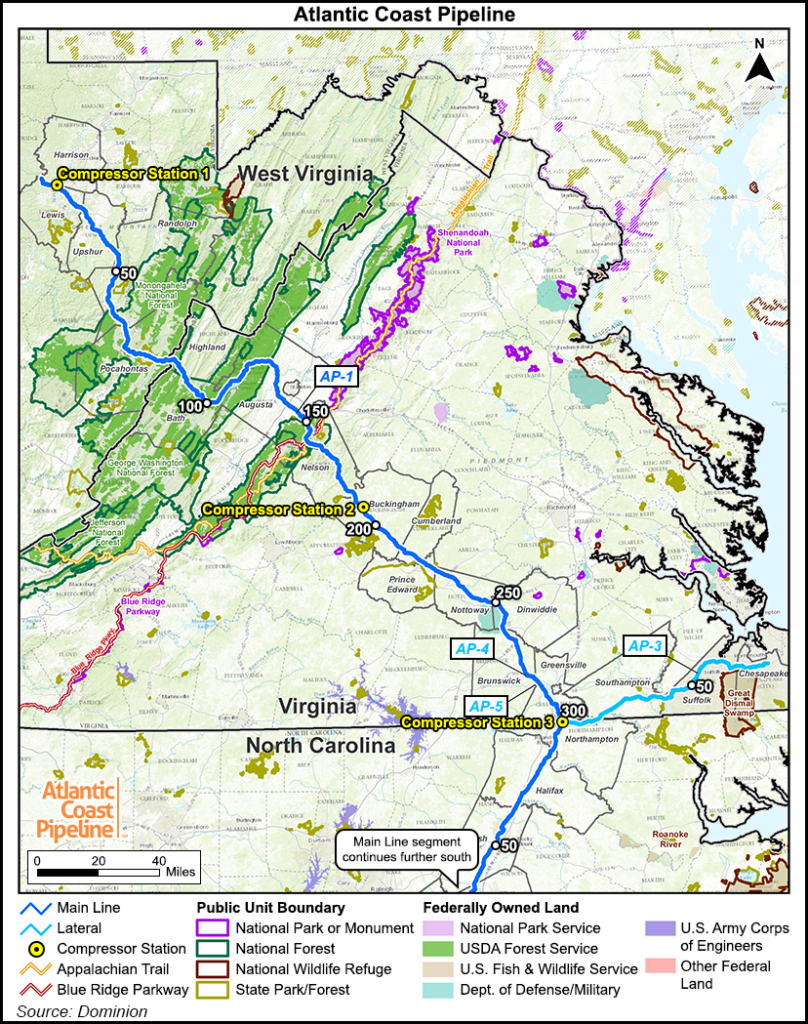

The 300-mile, 2 Bcf/d MVP would move Appalachian natural gas to markets in the Southeast and Mid-Atlantic via an interconnect with the Transcontinental Gas Pipe Line in southwestern Virginia. The 600-mile ACP would follow a similar path to move 1.5 Bcf/d of Appalachian natural gas from West Virginia, through Virginia and North Carolina to Southeast markets.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |