Shale Daily | Infrastructure | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Permian Basin

Severe ‘Takeaway Capacity Disorder’ Striking Permian, Says RBN Chief

The plethora of natural gas and oil supply clogging the Permian Basin has caused “severe cases of TCD, takeaway capacity disorder” that is going to take more than a few months to cure, according to RBN Energy LLC’s Rusty Braziel.

“For those of you not familiar with this affliction, it’s caused by too much of a good thing — more production volume than pipeline capacity to get those barrels, or those cubic feet to market,” Braziel told a standing-room-only audience last month at RBN’s inaugural PermiCon event in Houston. “The symptom of the disease is always the same: wide price discounts compared to major hub locations like Cushing and Henry.”

The cure is always the same too, he said. The feverish buildup of oil, natural gas and natural gas liquids (NGL) could use a shot in the arm from more infrastructure.

“The good news is that the recovery rate is almost 100%,” Braziel said. “Build the infrastructure and the market corrects itself.”

Symptoms could linger, though, and are likely to incapacitate operators working in the massive play off and on for years.

“The larger issue is selecting the right treatment,” i.e. the necessary pipeline, gathering system and processing plant, Braziel said. “Get it right, and you are cured. Get it wrong? Well, you don’t want to get it wrong.”

Permian gas production over the summer popped by about 8%, a gain of nearly 700 MMcf/d, with crude output topping 3.5 million b/d. In addition, record NGL volumes are flowing to the massive fractionation complex at Mont Belvieu near Houston.

“This market is moving so fast that if you blink, you’ll miss something important,” Braziel said.

Still, producers are finding much to like with the mostly healthy basin, with estimated half-cycle breakevens of $30-40/bbl. Productivity gains since 2014 have tripled, with the work of three rigs dropping to one.

The “dark side” to all the healthy productivity is maxed out infrastructure, Braziel said. Overcapacity hit the region in 2013 and in 2014, and “clearly, we are there again.”

Gas constraints came into focus beginning in 2016 as gas-heavy wells were developed in the Delaware sub-basin, led by Apache Corp.’s Alpine High project. By early this year, routes from the Waha hub in West Texas were nearly tapped out. Then price differentials blew out.

“And we have not seen the worst of the capacity constraints,” Braziel said.

One thing causing symptoms to linger is a lack of demand, with gas exports the only market that is growing, via pipeline to Mexico and from liquefied natural gas exports overseas.

For NGLs and oil, exports also are the means to an end, with most incremental Permian output headed to Gulf Coast export docks.

An estimated seven greenfield gas pipelines on the drawing board would add an incremental 14 Bcf/d. All but one of the proposed projects is to move supply to Houston or to Corpus Christi in South Texas.

Even if only five of the seven pipes are finished, producers then would be “talking about that bane of midstream infrastructure…overbuild,” Braziel said.

He expounded further on the dearth of Permian takeaway in a blog post this week. Some producers are dealing with constraints by reducing well completions and increasing flared gas.

Still, with close to 490 oil rigs working today in the Permian, a lot of associated gas has to find a home.

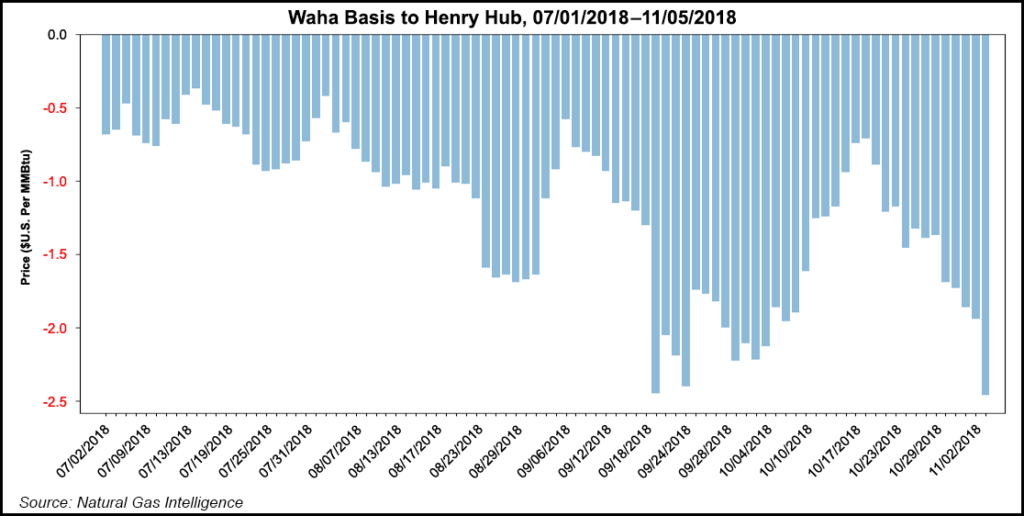

Since January 2017, average Waha basis has decreased from about minus 20 cents/MMBtu to average $1.50/MMBtu under Henry Hub for October 2018, Braziel said.

“But averages pale in comparison to the daily basis volatility, where October reeled between $2.20/MMBtu below Henry early in the month to only 70 cents/MMBtu by mid-month, then back to $1.70/MMBtu by the end of the month…” It fell to $1.94 Henry on Nov. 2.

Meanwhile, the front of the Waha forward basis curve “has collapsed from only about 50 cents/MMBtu below Henry a year ago, to about $1.60/MMBtu today. Only the anticipation of new pipeline capacity out of the basin in 2019 pulls Waha basis back into that 50 cent/MMBtu level by 2021,” Braziel said.

Gas exports to Mexico have climbed above 5 Bcf/d recently, but most of the supply hasn’t been from the Permian but rather from South Texas, Braziel said. Flows on the 3.1 Bcf/d of capacity from the Permian to Mexico “have languished, with volumes now just above 0.4 Bcf/d.”

Capacity to the border exists, but demand south of the border has held utilization to about 15%.

Utilization should improve, but “exports from the Waha market will struggle to get much above 1.4 Bcf/d (45% capacity utilization) between 2019 and 2023,” Braziel said.

A year from now things may look better for those seeking to move their gas out of the Permian.

Kinder Morgan Inc. is partnering in two massive Permian-to-Texas coast projects. The first, now underway, is Gulf Coast Express, which is set to ramp in the second half of 2019, providing about 2 Bcf/d of capacity.

That pipeline, however, won’t resolve the bottlenecks for too long, and constraints “will come back with a vengeance,” according to Braziel.

With Permian gas production continuing to increase, pipelines could reach maximum capacity again in 2020. Another Kinder partnership, Permian Highway Pipeline, also set to deliver about 2 Bcf/d, is tentatively set for completion in late 2020. While another gas pipeline project could come online “in the 2020-21 period, there will still be more Permian production than takeaway capacity by 2023, if not sooner.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |