Shale Daily | NGI All News Access | NGI Archives | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Pemex Gets Dinged by Rating Agencies Ahead of López Obrador Taking Office

Fitch Ratings has revised its outlook for the international issuer default ratings (IDR) of Mexico’s national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) to negative from stable, because of concerns about its direction once the new administration takes office Dec. 1.

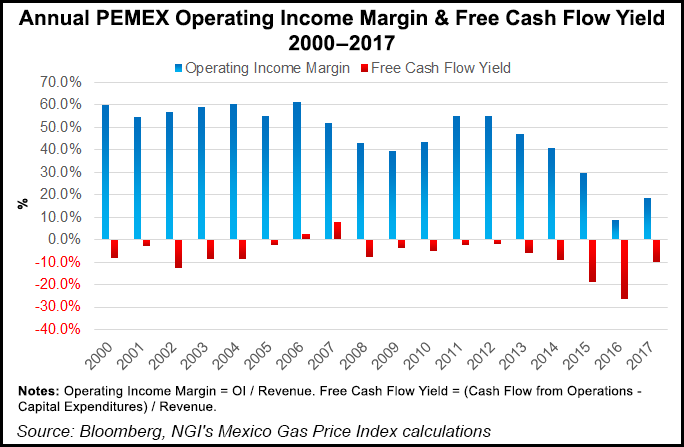

Analysts on Friday cited “increased uncertainty about Pemex’s future business strategy coupled with the company’s deteriorating Standalone Credit Profile (SCP), which could reach ”CCC’ from its current ”B-”.”

Fitch said if Pemex diverts capital expenditure (capex) from the upstream to the downstream segment, its SCP could continue to worsen.

The downgrade follows a warning last Thursday by Moody’s Investors Service regarding consequences if President-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador follows through on a recent pledge to end crude oil exports in order to boost domestic oil supply to local refineries.

“The new government’s energy plan, focused on fuel production self-sufficiency, sets it on a path to become a net crude importer by 2021, lacking enough of its own production to fulfill its increased refining demand,” Moody’s analysts said.

“The national oil company’s operating cash flow would decline and become more volatile under the new refining-focused business model, reducing its ability to pay taxes. Moreover, Pemex would be exposed to greater foreign exchange volatility, since its income from fuel sales would be in Mexican pesos, while 87% of its $104 billion debt as of June 2018 is in U.S. dollars (83%) or other hard currencies.”

López Obrador, who was elected July 1, has pledged multibillion dollar investments to boost utilization rates at the country’s six existing refineries, and to build one in the city of Dos Bocas, Tabasco state.

Better known by his initials AMLO, the president-elect has also criticized the 2013-14 energy reform that opened the formerly state-controlled energy sector to private investment. He said last week he plans to suspend exploration and production (E&P) bid rounds, a staple of the reform, until contracts awarded through previous rounds begin to show “results.”

Both López Obrador and his future energy secretary, RocÃo Nahle, publicly expressed their disagreement with the Fitch downgrade. Local press quoted the president-elect as saying that Fitch “should assume responsibility, because they endorsed the reform,” adding that, “not one barrel of oil has been extracted in four years.”

He also reiterated a previous assertion that the reform was a “complete failure.”

López Obrador blames the reform for the country’s declining hydrocarbon production and reserves, although output has fallen steadily since 2004.

Nahle, meanwhile, called the downgrade “absurd” in a radio interview, arguing that the new government’s proposals will “rescue” the oil industry and improve refinery utilization rates to between 90% and 100%, up from current levels of around 40%.

While López Obrador has expressed a reluctant willingness to work with international operators to reverse the trend of declining oil and gas output, he has made clear his view that the key to restoring production is to give Pemex a bigger E&P budget and more autonomy.

Local press also quoted him as saying that the government will “intervene” if the E&P contracts awarded through the reform don’t start producing soon.

Fitch analysts said they expect Pemex production and reserves “to continue declining over the medium term and to potentially stabilize after three to five years as current capex is insufficient to replenish reserves.”

The Fitch forecast directly contradicts López Obrador’s stated goal of bringing national crude output to 2.5 million b/d by 2024 from 1.8 million b/d currently.

“Fitch estimates Pemex will require an annual capex of around $15 billion to $18 billion to replenish reserves,” analysts said, citing that Pemex’s E&P budgets for 2017 and 2018 totaled $4.5 billion and $4.3 billion, respectively.

Pemex, which recently announced a $2 billion bond placement that was 5.9 times oversubscribed, is scheduled to announce its 3Q2018 earnings on Oct. 26.

“Fitch estimates production could decline 5% year/year the next two years and stabilize thereafter,” analysts said. “Potential increases in production from farm-outs, joint ventures and lower taxes could partially offset the production decline in the medium to long term.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |