NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | E&P | NGI All News Access

Mexico Faces Uncertainty Over Natural Gas Supplies For Industry as Pemex Output ‘Tanks’

Amid delays in the construction of key pipelines, the near absence of storage facilities and a slump in the production of state-owned Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex), Mexico appears to be on the brink of a severe shortage of natural gas.

In order to avoid what are known, as “critical alerts”, Sistrangas, Mexico’s main natural gas transmission network, must have a minimum load of 7 Bcf/d and a maximum of 7.7 Bcf/d, according to its operator, the Centro Nacional de Control de Gas Natural (Cenagas).

But at 5 a.m. on Monday, the minimum load was just over 6.8 Bcf, according to an official document seen by NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index. The document indicated that the figures showed a high risk of a critical alert.

On the previous Wednesday, Oct. 17, the Sistrangas load was even lower than the minimum target load, at 6.579 Bcf/d. Of the total figure, pipeline imports amounted to 3.133 Bcf. The remaining 1.675 Bcf was injected by Pemex, either as dry gas direct from the wells or from the company’s gas processing centers.

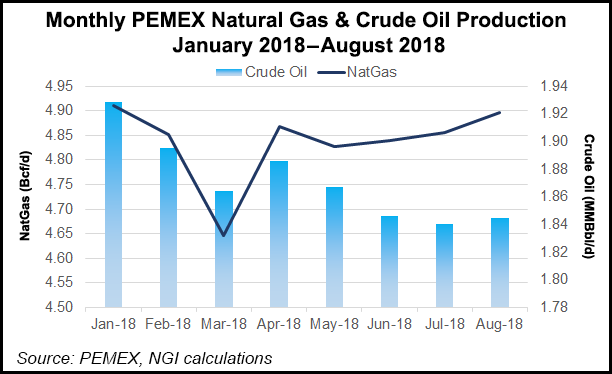

The figures show that the biggest problem is that “Pemex production is tanking,” a ministry source told NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index. In August of this year, Pemex produced 3.849 Bcf/d of natural gas, down by 7.7% from 4.170 Bcf/d a year earlier.

Where risks of a critical alert emerge, Cenagas resorts to short-term system balancing using the storage of the liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals at Altamira, Tamaulipas, on the Gulf Coast and Manzanillo, Colima, on the Pacific.

Cenagas has chosen four depleted oil and gas reservoirs for a tender to build a strategic underground gas facility with at least 10 Bcf of storage, the first of a total of 45 Bcf proposed by 2016 in an Energy ministry document published early this year.

The tender was to be launched in September but no announcement on it has been made.

Arturo Carranza, of the National Institute of Public Administration, points out that any pain over a shortage of gas will not be spread evenly in geographic terms. The nation’s northern industrial capital of Monterrey is well supplied with transport infrastructure and is the nearest nodal point from the gas fields in Texas.

“By contrast, for example, Guadalajara in the west is likely to draw a very short straw if and when the shortages become acute,” Carranza said. “And, of course, southern and southeastern Mexico have problems of their own.”

Pedro Joaquin Coldwell, the Energy Secretary, addressed the problems of the south this past weekend. Speaking at a chemical industry forum, he admitted that gas would be in short supply in the south through the end of the year and into early 2019.

By then the $1.3 billion Sur de Texas-Tuxpan underwater pipeline, which stretches nearly 500 miles through the Gulf of Mexico from Brownsville, in South Texas to the Tuxpan port in Veracruz state, Mexico, is due for completion. The pipeline has a capacity of 2.6 Bcf/d.

At more or less the same time, a $38 million contract is to be completed to reverse the direction of a Pemex compressor station at Cempoala, Veracruz, that was originally built in 2007 to inject gas from south to north.

At that time, of course, the bulk of Mexico’s consumption of gas came from the oil and gas fields of Pemex in the southeast, from where it had to be transported to the industrial center and north of the nation.

Now, with Pemex production sharply declining, and imports from the United States booming, the very opposite is true.

On Tuesday, the newspaper Reforma reported that industries in southeastern Mexico have been told by Pemex that it will not be able to provide gas to its clients for most of November. The alternative, Reforma added, was to buy LNG at about four times the price. Cenagas would make the arrangements, it said.

However, late Tuesday afternoon, Pemex announced there will be no shortage of natural gas in southeastern Mexico, confirming the delivery for November of 100 Bcf/d for its southeastern Mexico customers through first-hand sales.

To add to the uncertainty over natural gas supplies, the future management of Cenagas is unclear. Cenagas is a state company, as are Pemex and the Comision Federal de Electricidad, the CFE power utility.

The Pemex and the CFE are tightly controlled by the government, and their chiefs are frequently reshuffled at the whim of the nation’s president. Cenagas is a much less political institution.

Already, the identities of the future heads of Pemex and the CFE under the upcoming administration of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, which begins Dec. 1, have been clearly identified for many weeks.

David Madero, the current head of Cenagas, may well be clearing his desk to prepare for a successor, but there has been no official announcement.

And that suggests that he might be retained under the new government. “Madero is an excellent public servant with great technical expertise,” said Arturo Carranza. What is more, he added, in reference to the obvious political ambitions of many former state company chiefs, “he has no political ax to grind.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |