Regulatory | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Natural Gas Serves Both Short, Long Term Climate Goals, Says Shell Exec

Debating whether natural gas is a bridge fuel or a destination fuel misses the point and distracts from the changes that need to take place right now to achieve the required decarbonization of the world’s energy system, according to Royal Dutch Shell plc Executive Vice President De la Rey Venter.

Venter, head of Integrated Gas Ventures for the supermajor, said current debates surrounding natural gas and its role in tackling climate change too often focus on the long-term goal at the expense of recognizing the value of near-term progress in tackling the immense challenges inherent to such an unprecedented energy transition.

“We, the big ”we,’ want to radically transform the global energy system so that it transitions to becoming a net zero greenhouse gas emissions energy system over the next 50 years starting now,” Venter said during a keynote speech last Monday at the North American Gas Forum, hosted by Energy Dialogues LLC.

“We want to deliver on the aims of the Paris agreement,” Venter said, referring to the United Nations accord reached in late 2015. “This is a must-win battle for our planet, not a nice-to-have. We believe it must happen, and we believe it is actually possible. That is what we want, and we are by and large united on this long-term goal. So why then is it so hard to act as if we are aligned?”

Venter alluded to the “plethora” of divisive arguments that have taken place recently focused on labeling one energy source good and another bad, arguments that often focus on the goals but not the realities of how to achieve them. The discussion must shift to unpacking what it will take to ultimately decarbonize each sector of the energy system, the costs, the practical challenges and the uncertainties, the executive said.

“But we must also drive for progress in every sector of the energy system over the very near-term,” Venter said. “This is often downplayed in the narrative, and it is so wrong. Because the uncomfortable truth is that what will happen to our planet in the end is not a function of what we achieve by 2070, but it is a function of how much greenhouse gas we will have pumped cumulatively into the atmosphere between the start of the industrial revolution and when we eventually achieve a net zero emissions energy system.

“And therefore, what happens tomorrow, what happens next year and over the next decade, matters greatly.”

Venter didn’t mince words about the scope of the challenge ahead, projecting that the world will need about five times as much power production over the next 50 years as has been added over the past 140 years.

“We are not having more meaningful, reflective and informed dialogues on what it will really, really take in practice to get there, and to get there around the world, not just in Norway, or in the Netherlands, or California,” he said. “Because we need to be level-headed on the scale of this ambition.”

The world will need to reach a point where “gross emissions actually start to fall despite us adding over the course of this century as much new energy system capacity as has been created since the start of the modern era, and we cannot create that endpoint soon enough, which is an important consideration when you think about the ways in which gas can help deliver this energy transition.”

Looking at the power sector, Venter described a future where renewables become “the dominant force in power generation” but where gas plays a major role in managing cyclical swings in demand for both electricity and heat.

Natural gas also has an opportunity in emerging economies, he said, describing an “optimal future power system” featuring “lots of renewable energy distributed all over the grid and…just the right amount of gas-fired power close to the main centers of demand, balancing the grid, providing grid resilience and handling the big cyclical swings.”

Particularly for urban centers, gas-fired power has advantages because of its low upfront capital requirements and smaller physical footprint compared to some other forms of energy, he said.

But near-term changes matter just as much as figuring out what the long-term sustainable solutions will be, according to Venter.

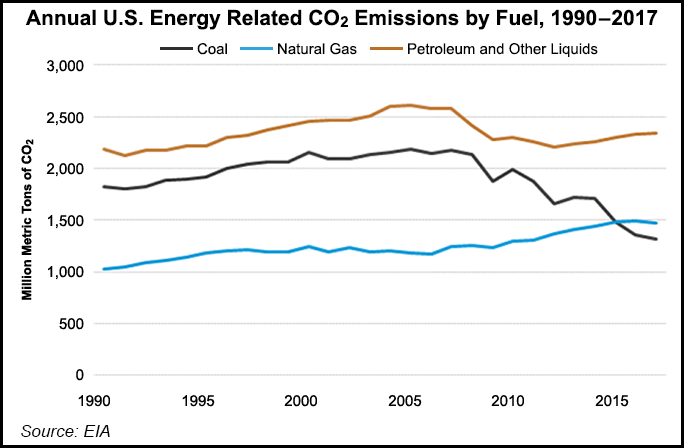

“The single biggest opportunity for our planet to bend the emissions trajectory downward over the next decade or two is the large-scale replacement of coal in the power sector with renewables and gas. This needs to happen now. In the very near-term,” he said. “…It really does not matter whether in 2070 the share of gas in the power mix is X percent or Y percent, what matters is that deep decarbonization happens in the power sector, that this journey is accelerated in the here and now and that we use every tool at our disposal to make this happen.”

Outside of the power sector, there are some segments of the global energy system that “can and should be electrified” to reduce carbon emissions, such as passenger mobility. But others, such as heavy industry and heavy-duty transport, including marine and aviation, will not be so easy to decarbonize. Once again, here natural gas has a “powerful role” to play, according to Venter.

In the shipping industry, transitioning to using liquefied natural gas could “immediately vastly reduce” emissions, and the same principle could apply for trucks, buses, heavy engines and industrial complexes.

Whether ships or trucks are eventually powered by zero-emissions hydrogen or some other source doesn’t matter in the here and now.

“These options are not available at an affordable cost for us today, or in the foreseeable future, and by the time different options” become available “the engines we buy today will have had their economic lives, and we will replace these machines with the best available and affordable thing at that time,” Venter said. “So what then do we really gain from a debate over whether gas is a destination fuel in 2070 or a bridge to the future? I personally think we don’t gain much at all.”

Citing Shell’s commitments to crack down on methane emissions, Venter said this is a “first order issue” for the natural gas industry as it establishes its role in tackling climate change.

“Rightly, methane is getting a lot of scrutiny, and whether methane’s global warming potential should be evaluated over 20 years or 100 years is not the point,” he said. “The point is…that gas must remain in the pipe or in the tank until it gets to the burner tip, that we need to get very, very good at finding and fixing methane leaks, and that the world deserves to know, with accuracy, how much methane escapes from the natural gas value chain.

“Every responsible participant in the natural gas industry…should work towards making this happen in the fastest, most cost-effective and most pragmatic way.”

Echoing others in the industry, Venter said carbon pricing can’t come soon enough.

“But it needs to be meaningful, and it needs to be global,” he said. “We will never get to where we need to be…without a price on carbon. Period. It needs to happen…It would be great if the U.S. was to lead on that.”

Venter’s comments come after Shell CEO Ben van Beurden recently made a forceful case about the future of natural gas in a decarbonizing world.

The portfolio will continue to evolve, van Beurden said at the recent Oil and Money Conference in London, and alternative energies are to become a “bigger part of what we do. But that pace of change will be linked to the pace of change in society. We do plan to be at the forefront of change in our industry, but we cannot and will not seek to dislocate ourselves from the people who buy our products.”

Shell’s core business “for the foreseeable future” is “very much in oil and gas, and particularly in natural gas…Oil is going to be needed by this world for a long time to come, and gas even more so.”

Those comments echoed the sentiments expressed by BP plc Group CEO Bob Dudley at the same conference.

“I think we are standing at a fork in the road, and we need to decide which way to go,” Dudley said. “We could go the way of people who want to drive a wedge between the energy industry and investors — between oil and money, if you like. They push for potentially confusing disclosures, raise the specter of a systemic risk to the financial system from stranded assets and campaign for divestment, all in an effort to squeeze oil and gas out of the fuel mix.”

The people pushing for change “are driven by good intentions, but my concern is that their suggested recommendations could lead to bad outcomes, particularly for some of the most vulnerable people in the world.”

Venter’s comments also came the same day that FERC Commissioner Cheryl LaFleur described a “complicated relationship” between natural gas and climate change that has created new challenges for the agency’s pipeline certification process.

“The facts haven’t become any more complex, but the ways that they’ve been looked at seem to be more complex,” LaFleur said. While natural gas has helped curb carbon emissions, “on the other hand, as events have moved on, more people are pointing out that natural gas itself has its own greenhouse gas implications” that are “smaller than coal but potentially less than carbon-free ways to make electricity.

“…For the people who are in the gas industry, getting ahead of this issue is really important, because I don’t think it’s going anywhere.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |