NGI Mexico GPI | E&P | NGI All News Access

Mexican Energy Secretary Reminds Legislators of Fracking’s Long History in Country

Mexico has used hydraulic fracturing (fracking) for considerably more than half a century, and the technique is currently applied to about one in five conventional oil and gas wells, Energy Secretary Pedro Joaquin Coldwell said during a hearing on Thursday before the Chamber of Deputies, the nation’s lower legislative chamber.

President-Elect Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has indicated that his government, which takes over Dec. 1, would ban fracking from unconventional deposits, which the U.S. Energy Information Administration has estimated are among some of the richest in the world, including a south-of-the-border extension of the Eagle Ford Shale.

Lopez Obrador’s remarks were not addressed to the industry, but to the general public. As a result, there have been suggestions that he has been speaking only about high-volume hydraulic fracturing (HVHF), which combines more volumes of water, proppant and additives to unlock oil and gas from source rock deep beneath the surface. Joaquin Coldwell attempted to clarify the distinctions between the older methods of well stimulation and the newer technologies to show how it might benefit Mexico in the hugely lopsided trade of natural gas with the United States.

“People, when they talk about hydraulic fracturing, they seem to think that it’s something new,” Joaquin Coldwell told the chamber. “But the fact of the matter is that it’s been used in Mexico since 1960. Some 22% of our conventional fields have used one form or another of fracking.”

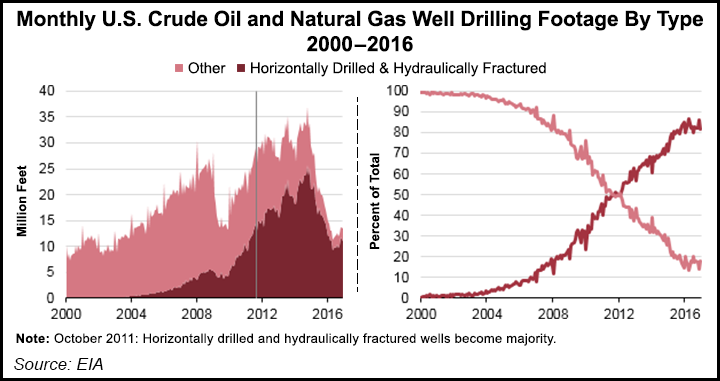

What’s new, he said, is that in recent years HVHF has become an ideal technique for producing gas in the United States. The technology sparked a gigantic economic revolution, he noted.

“I would lament the day that a generalized ban on fracking were to be imposed on our country,” he said. “That would be a very big mistake, and on that very day there will be a huge fiesta in Texas for the gift that we Mexicans will be giving by condemning us to import so much gas.

“More than 50% of our gas reserves are in non-conventional resources, and the only way to extract them is by hydraulic fracturing.”

Joaquin Coldwell’s intervention is the first of a top-flight political figure in an attempt to counter the anti-fracking lobby, dominated by environmentalists of varied interest groups that form Lopez Obrador’s Morena party, which won him a landslide victory in July’s presidential election.

Fracking, and its social media image of a blight on the planet, is not the only issue facing companies that aim to develop unconventional resources in Mexico. The first auction of nine onshore blocks scheduled for February in Round 3 of the 2013-2014 energy reform are in the northern Gulf state of Tamaulipas.

American travel advisories have consistently warned U.S. citizens to stay away from Tamaulipas because of the high levels of crime. At the very least, said editor and publisher David Shields of Energia a Debate magazine, high security costs will have to be factored into unconventional development in the region.

Additionally, land holding and mineral rights provide a much greater challenge than they do in the United States. Whatever happens, Shields has said, Mexico will have to provide generous incentives to lure companies to the nation’s onshore fields.

To be sure, the debate over fracking continues well beyond the shores of North America. Following setbacks, the British government granted approval for fracking to take place at a site in northwest England, where two wells are to be drilled by Cuadrilla Resources. That decision followed a Lopez Obrador-style fracking ban that lasted for seven years in the UK.

Meanwhile, unconventional resources may amount to four times Colombia’s total reserves. Ecopetrol, the Colombian state oil company, recently revealed its plans to focus on unconventional exploration in its most prolific region, Magdalena Medio, or “The Middle Mag” as oil workers call it.

The Cretaceous Luna and Tablazo formations in Colombia converge and are estimated to hold 30 billion boe. The debate over fracking is still raging.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |