E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Mexican Regulators Suggest Spin Off of Pemex’s Natural Gas Business

Mexico’s upstream regulator has urged the government to spin off a separate natural gas company from state oil company Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex), along the lines of Russia’s Gazprom, or BP Gas that emerged from the umbrella of the UK-based oil major.

The suggestion from the regulator, the Comision Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH), is contained in a policy document presented last week to an audience of business and academia leaders.

In addition to the spin-off, CNH suggested rejecting a ban on hydraulic fracturing (fracking) to exploit Mexico’s extensive, but almost entirely unexploited, shale deposits. Although no ban has been formally proposed, President-elect Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador recently stated that the country “will no longer use that method to extract petroleum” from shale.

CNH also suggested creating a Mexican “hub” to transport natural gas produced in the United States for export to Asia, which would create substantial cost savings by avoiding the Panama Canal. The suggestion, which came from the floor of the gathering, was warmly received by CNH President Juan Carlos Zepeda.

CNH Commissioner Hector Moreira, a former deputy energy secretary, said a natural gas spin-off from Pemex was vital to ensuring the nation’s energy security.

“If you ask Pemex executives why their priority is the production not of gas but of oil, they reply that the answer to the question is obvious: oil prices are much higher than those of gas, and so provide a much higher return on capital investment,” Moreira said. But that view begs the question of the importance of the importance of natural gas in a value chain that runs through power generation to petrochemicals and beyond, he added.

Mexico depends on U.S. exports to meet 84% of its growing demand for natural gas. Yet in per capita terms, Mexico’s potential for natural gas production is higher than that of the United States, according to Moreira, despite output that peaked at 7.03 Bcf/d in 2009. Current production is about 4.8 Bcf/d.

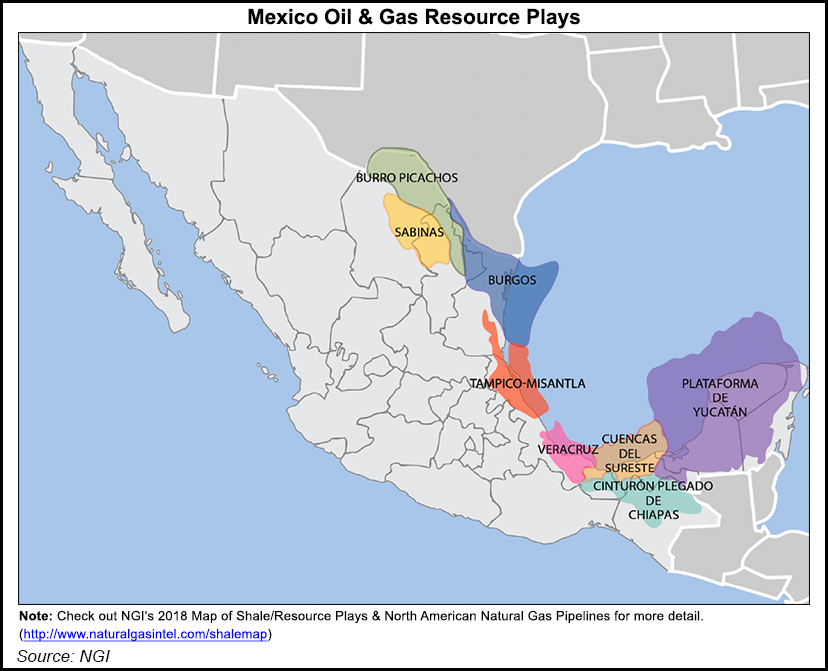

According to the EIA, Mexico’s unproved wet shale gas technically recoverable resources totaled 543 Tcf in 2013, compared to 567 Tcf in the United States. Major gas-specific development programs have been shelved or abandoned on land, offshore and in deepwater amid government-imposed spending cuts on Pemex in recent years, Moreira said.

The proposed Pemex spin-off would presumably require very substantial upstream spending in order to reverse the downward trend of recent years, especially since Lopez Obrador’s future government plans to increase the government’s budget on remedies for such social ills as poverty and crime. To raise money, an audience member suggested that the gas spin-off have an initial public offering.

Zepeda recently proposed a formula in which Pemex could have access to international capital markets. George Baker, publisher of Mexico Energy Intelligence, has proposed a formula that would conserve the current role of Pemex as a government agency administering its legacy projects while forming a unit that could be floated on stock markets and have alliances with foreign companies both at home and abroad.

Pemex, like Petroleos de Venezuela SA and Saudi Aramco, are fully state-owned. Other national state-owned oil companies have privately held minority shareholdings. However, a Mexican shale offensive would require much more than capital in the event of ban on fracking. Mexico already has problems such as inadequate infrastructure and restrictions on landholding and mineral rights that would make it very hard to compete with the U.S. shale industry.

If Lopez Obrador’s remark on fracking means a ban rather than simply adequate regulation of the technology, “we would have to cancel our plans for Mexico,” one leading foreign company that has been aiming to form part of a vanguard of a Mexican shale revolution told MGPI.

Zepeda and CNH Commissioner Alma America Porres argued that fracking is a well-established technology and that Mexico’s regulatory framework insists on the use of brackish or wastewater.

“Fracking has been used in Mexico for 50 years or so,” Porres said, though presumably she was not referring to the “high volume” fracturing used in the U.S. shale industry.

CNH was founded to both regulate the industry and formulate upstream policy, but that was a decade ago, well before the 2013-14 energy reform. Zepeda emphasized that CNH can only advise the government in terms of policy; it cannot overrule any policy decisions by Lopez Obrador as the nation’s president.

An audience member also suggested that Mexico serve as a hub for U.S. natural gas exports in the form of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to Asia. Zepeda gave the proposal an enthusiastic response.

“Our economic studies department has already suggested that exports of LNG from a liquefaction plant at a port on Mexico’s Pacific Coast would probably cost save about 30% in transportation costs than those of the Panama Canal,” he said.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |