NGI Archives | NGI All News Access | NGI Mexico GPI

Mexico E&P Bid Rounds, Farm-Outs Still on Table, Says López Obrador Adviser

The suspension of oil and gas bid rounds by Mexico’s next government will hopefully only last a few months, according to one of President-Elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s (AMLO) top energy advisers.

Speaking Wednesday at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, Fluvio RuÃz Alarcón also said the next administration will respect the 107 contracts awarded through bid rounds so far under current President Enrique Peña Nieto.

The rounds have been conducted under the framework of a 2013 constitutional reform that opened up the energy industry, formerly a state monopoly, to competition from the private sector.

López Obrador caused a stir recently when he said that the rounds would be suspended, pending a review by his transition team of the awarded contracts for irregularities.

The rounds have been “transparent from my point of view,” said RuÃz, who is a petroleum engineer and former Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) board member. “I don’t think we’re going to find any corruption acts.”

The main purpose of the review, RuÃz said, is to study the different contract models used, in order to determine which ones will be optimal for future bidding processes.

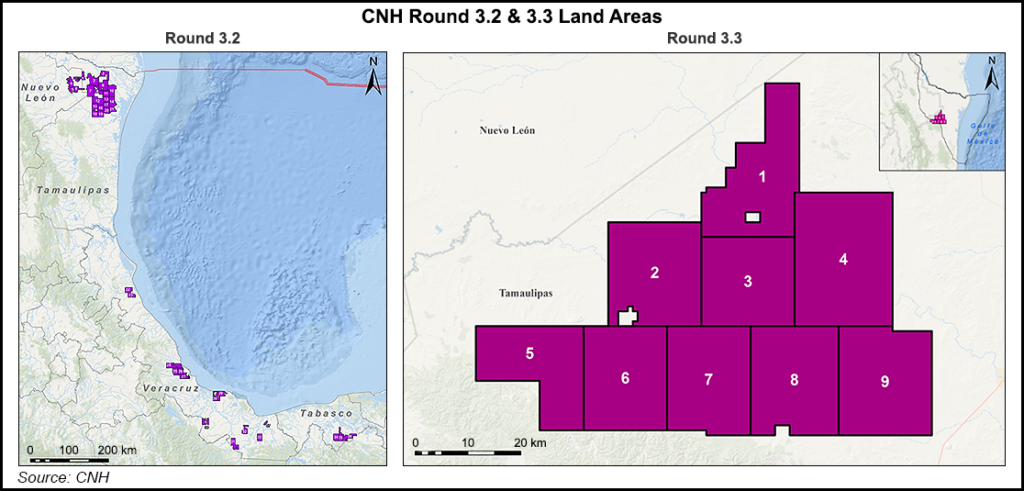

Rounds 3.2 and 3.3 for onshore acreage, plus a farm-out tender for stakes in Pemex acreage, are officially scheduled for February 2018, although López Obrador is expected to follow through on his pledge to postpone them after he takes office on December 1.

Asked how long he expects the rounds to be delayed, RuÃz could not give a precise date, but said he hoped they would resume by the end of 2019.

Prior to the 2013 reform, private sector firms could only participate in Pemex projects via service contracts, a mechanism that would continue under López Obrador. The president-elect announced recently that his administration will launch a drilling services tender in early December for fields in the southeast part of the country.

RuÃz reiterated his own previous assertion that Pemex will take advantage of its newfound ability, under the reform, to farm-out ownership stakes in exploration and production (E&P) blocks to private sector firms. The difference is that the new government will seek legislative changes to give Pemex more autonomy in selecting its partners.

“That’s why we [want] to postpone the farm-outs. Not because we don’t like [them],” RuÃz said. “It’s exactly the opposite. We are convinced that it’s one of the most important tools that Pemex received from the energy reform.” RuÃz said that the farm-outs would allow Pemex to share geological and financial risk, particularly in high-risk plays such as those in deepwater.

“We think that Pemex should become a real company,” RuÃz said. “Now we are in the middle, sometimes as a company, sometimes as a public entity.”

Asked if there is a model internationally on which he thinks Pemex should be based, RuÃz cited Norway’s Equinor ASA, formerly known as Statoil, and Brazil’s Petróleo Brasileiro (Petrobras).

The governments of Norway and Brazil hold ownership stakes of 67% and 64%, respectively, in Equinor and Petrobras. Shares of both firms trade on the New York Stock Exchange. Pemex, meanwhile, remains 100% state-owned.

Multiple news outlets have reported that RuÃz is López Obrador’s top pick to lead Pemex Exploración y Producción, the company’s E&P subsidiary.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |