Markets | Mexico | NGI All News Access | NGI Mexico GPI | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Regulatory

Corruption Still a Concern in Mexico Public, Private Sectors, Study Finds

Corruption is becoming “normalized” in Mexican society, a trend driven in part by the energy sector, according to new research.

“Mexico is a prime example of how corruption has expansive effects on a society and how it is subsequently normalized by society,” the Baker Institute for Public Policy’s Jose I. Rodriguez-Sanchez, postdoctoral research fellow in international trade, argued in an issue brief published earlier this month. “Cases of corruption in Mexico have increased in recent years in both the public and private sectors.”

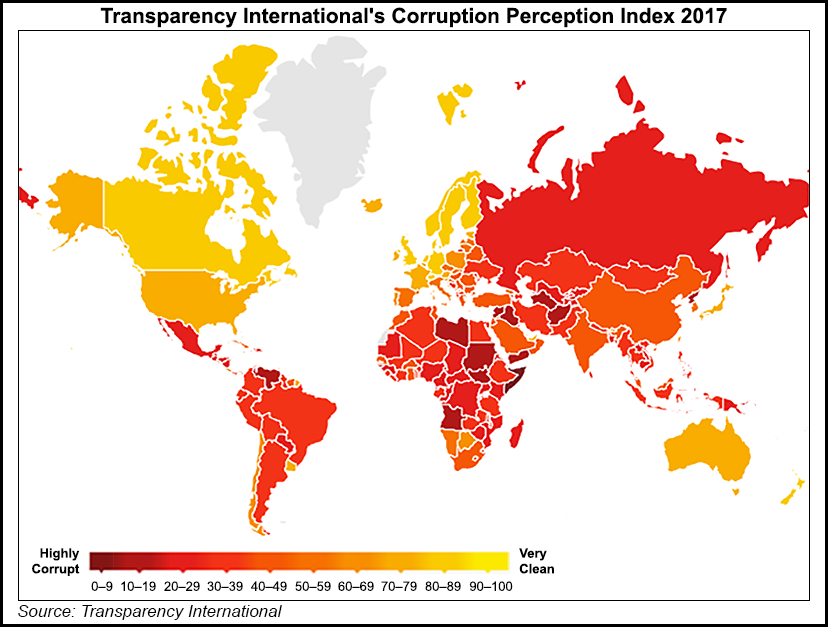

The country ranks near the bottom of multiple indexes that measure corruption, Rodriguez-Sanchez highlighted. What’s more, “According to the IMCO [Instituto Mexicano para la Competitividad], almost all corruption crimes go unpunished in Mexico. Between 1998 and 2012, only 1.75% of individuals accused of corruption faced charges in Mexico. From 2000 to 2013, 42 Mexican governors were accused of corrupt actions, but only five (11.9%) were ultimately convicted.”

National oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) has helped foment the trend, Rodriguez-Sanchez argued, citing that the state-owned firm “signed and paid contracts to private companies that were very problematic in exchange for $11.7 billion from 2003 to 2012. These firms overcharged Pemex for their work, and in some cases, the work was of poor quality or never completed.”

The suspicious contracts and subsequent inaction by Pemex, which has historically supplied around 30% of the government’s revenue, were first reported by Reuters in 2015.

Rampant corruption and violence were the central themes in Mexico’s 2018 presidential election, with the populist candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador sweeping to a landslide July 1 victory on a pledge to eradicate both.

However, a lack of detail on how he will do so have led some analysts to question the veracity of his rhetoric. What’s more, López Obrador’s Pemex-first energy platform centers largely on plans to obtain fuel self-sufficiency through a revamp of Pemex’s six existing oil refineries and the construction of a new one in his home state of Tabasco.

Refining projects undertaken by national oil companies in Latin America have become practically synonymous in recent years with delays, astronomical cost overruns, and major corruption scandals. The most prominent examples are the Abreu e Lima refinery commissioned by Brazilian state oil company Petróleo Brasileiro (Petrobras) and the Reficar project by Colombia’s Ecopetrol.

Media reports also alleged that former Pemex CEO Emilio Lozoya received a $10 million bribe from Brazilian construction giant Odebrecht, the same firm implicated in the Petrobras scandal, in exchange for a contract to carry out modernization works at Pemex’s Tula refinery. Mexico authorities never brought charges against Lozoya, reportedly due to pressure from the government of President Enrique Peña Nieto.

Whether the next government will take concrete steps to fight these types of cases, as well as the rapidly growing problem of fuel theft through the illegal tapping of pipelines by criminal organizations, remains to be seen.

Citing IMCO estimates, Rodriguez-Sanchez said that corruption costs Mexico anywhere from 2% to 10% of GDP annually.

“The common Mexican phrase ”El que no tranza, no avanza, or ”The one that does not cheat, does not succeed,’ must be extinguished from Mexican society,” he said.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |