Infrastructure | Markets | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Regulatory

Oyster Creek Nuke Retires; Gas Demand Set to Grow as Wave of Retirements Planned by 2023

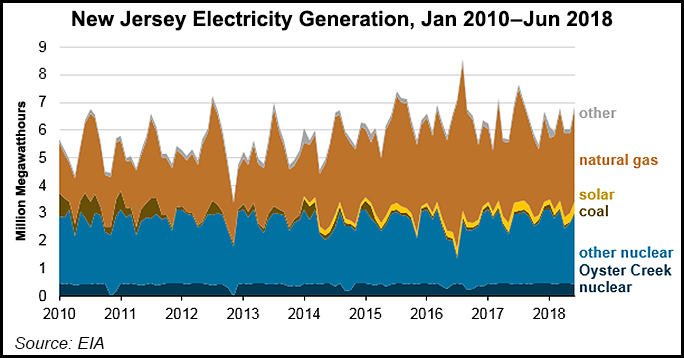

When the Oyster Creek nuclear reactor shutters its doors for the last time on Monday, it will be the first of nine nuclear facilities set to retire in the next five years, setting the stage for U.S. natural gas demand to grow by as much as 1.64 Bcf/d.

The 625-MW Oyster Creek reactor joins the Pilgrim, Three Mile Island, Duane Arnold, Davis Besse, Indian Point, Beaver Valley, Palisades and Perry nuclear plants that are set to retire by 2022, together taking more than 9,000 MW of generation off the grid.

“Economic factors have played a significant role in decisions to continue operating or to retire nuclear power plants, as increased competition from natural gas and renewables has made it increasingly difficult for nuclear generators to compete in electricity markets,” the Energy Information Administration (EIA) said.

Indeed, natural gas prices have declined dramatically since onshore shale development spurred a new wave of gas production, falling to a sub-$3 average so far in 2018, down from an average $8.90 a decade ago. EIA expects additional unplanned retirements will reduce total U.S. nuclear generating capacity from 99 GW in 2017 to 79 GW by 2050.

With the wave of nuclear generation expected to retire in the next five years, natural gas is expected to capture much, but certainly not all, of that market share. The Oyster Creek unit operated at a 99% utilization rate (or 620 MWh/day on average) in 2017, “which makes sense for a nuclear plant, as they generally run at the base of baseload generation,” according to Genscape Inc. natural gas analyst Joe Bernardi.

Assuming a 1:1 replacement of the lost nuclear capacity with natural gas, the 620 MWh/d should correspond to no more than 114 MMcf/d of new gas demand. “The actual number will be less than that due to the 1:1 replacement assumption not being what will really happen,” Bernardi said.

Oyster Creek, which went into service in December 1969, was the oldest commercially operated nuclear power plant in the United States. Given its aging infrastructure, the decision to close the unit was made in 2010 as owner Exelon Corp. faced estimated costs of more than $800 million to install cooling towers to meet new environmental standards. There were also concerns about local water safety.

New Jersey Sierra Club Director Jeff Tittel applauded Oyster Creek’s closure, saying the facility was “a disaster waiting to happen” and the closure was “long overdue.”

The plant’s originally scheduled 2020 retirement was moved up a year to align with its fuel and maintenance cycle. Despite the nuclear plant’s official shutdown on Monday, the facility’s decommissioning phase that follows is a lengthy six-step process that could continue for 60 years, meaning parts of the plant itself could remain in place until 2075.

“The decommissioning and dismantling of this plant should be done as soon as possible,” Tittel said, noting that the plant itself “is falling apart” and located on a site vulnerable to sea level rise. “It’s important that the plant is finally closing, but we need to be sure it’s done right.”

Two other nuclear facilities are expected to be retired in 2019 — Exelon’s 837-MW Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania and Entergy Corp.’s 688-MW Pilgrim in Massachusetts.

While electric grid operator PJM has said none of the planned nuclear retirements pose any threat to fuel security in its region, a recent period of unexpected strong demand highlighted the fragility of the Independent System Operator New England (ISO-NE).

Gas Replacing Most Lost Nuke Capacity in New England

On Sept. 3, Labor Day, real-time power prices in the region spiked to more than $2,400/MWh as demand was much stronger than expected and as ISO-NE had some 1,766 MW offline. In order to maintain reliability, the grid operator resorted to two emergency procedures.

While the procedures didn’t require mandatory load shedding and rolling blackouts, they did halt maintenance activities and depleted 30-minute reserves. New England also asked market participants to reduce energy consumption and arranged for the purchase of emergency capacity and energy from neighboring regions.

“Labor Day weekend and other public holidays often bring lower demand profiles but can be tricky, and the script can flip every once in a while,” said Morningstar Commodities Research associate Dan Grunwald. “In this case, the holiday brought additional heat and demand that caught the region off guard.”

The ISO initially projected a peak load of 20,420 MW, while actual demand climbed as high as 22,956 MW, a significant 2,400 MW miss. While that level was still well under the demand extremes the region can experience in both summer and winter, New England can experience considerable differences between overnight baseload demand levels and the daytime peak, resulting in real-time prices ranging from minus $20/MWh to more than $80/MWh.

“Although this is by no means rare in a power market with an efficient pricing system, it is not a comforting sign when the ISO has to resort to emergency procedures at demand levels well below maximums,” Grunwald said.

Meanwhile, the 1,766 MW in outages was still generally low compared with historical levels, but ISO-NE still had to call on the higher-cost portion of its generation stack to meet demand. Outages all summer only fell below 1,000 MW a few times, “so the extra 766 MW shows the current sensitivity of the stack to shifts,” Morningstar said.

One notable outage was the Pilgrim facility, which was also out due to transmission line issues during the bomb cyclone last winter. The fact that Pilgrim was once again offline when ISO-NE needed it most is not entirely surprising, given Entergy’s deal in August to hand the plant over for retirement by next June, Morningstar said. This circumstance highlights the risk that as baseload units retire, ISO-NE “shifts more often into a reliability situation” that results in the need to implement emergency procedures.

“As Pilgrim retires next summer and other older baseload coal and natural gas plants exit the stack in the next couple of years, the ISO-NE will have fewer resources to stave off the need to resort to emergency procedures. Keeping these older plants going is not necessarily the answer either as with age comes less reliability, regardless,” Grunwald said.

The main replacement capacity coming online so far this year and projects slated for next year are more efficient gas plants. All told, an additional 1,579 MW in gas generation has come online so far this year and another 1,126 MW is set to be in operation by the time Pilgrim is set to retire next June.

“There is plenty of fossil fuel capacity coming online in New England, but it almost all relies on a single fuel source that is already constrained,” Grunwald said. This may be why there is a mix of combined cycle and combustion plants being built instead of just combined cycle.

The added possibility of supply interruptions limits the added efficiencies of building combined cycle plants, and it may be more practical to build plants that provide the flexibility to ramp up and down faster, he said.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |