Few Clear Signals for Mexico’s Fledgling Natural Gas Market as AMLO Prepares to Take Office

Following the decisive and historic victory of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador in the July 1 presidential election, Mexico’s natural gas sector is in wait-and-see mode as the dust settles from the campaign and the new administration prepares to take office.

The months of campaigning before the election were full of rhetoric but short on specifics, leaving many in the energy industry guessing as to exactly what policies the next administration would implement. Lopez Obrador, popularly known by his initials AMLO, won the presidency with more than 50% of the vote. He also appears headed to a supermajority in the Congress, which would give him a broad mandate for his six-year term that begins Dec. 1.

“Everyone is trying to read the tea leaves at this stage, and given the archaic five-month transition period in Mexico, there will remain a tremendous amount of speculation as to policy approaches to be taken leading up to AMLO taking over in December,” IPD Latin America’s John Padilla told NGI’s Mexico GPI.

“The encouraging sign has been the very focused effort to calm markets starting the night of elections, and in each of the orchestrated statements and interviews that he and cabinet members have made since.”

In the days and weeks after the polls closed, Lopez Obrador and his top energy adviser, Rocio Nahle, have each signaled that they do not intend to reverse the 2013-2014 energy reform implemented by the outgoing president, Enrique Peña Nieto.

During the campaign, however, AMLO was a vocal critic of the reform. He pledged, among other things, to review the exploration and production (E&P) contracts awarded in Mexico’s nine upstream licensing rounds to date. The review would check for irregularities in the contracts, part of a broader anti-corruption plank in the platform of Lopez Obrador’s party, Movimiento Regeneracion Nacional (Morena).

In the past few days, Mexican regulators have decided to postpone three ongoing upstream tenders — two onshore licensing rounds and a farmout auction by state oil company Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) — until after the December inauguration, partly to allow more time for the contract reviews.

However, little was said during the campaign about the natural gas sector, which is transitioning to a competitive wholesale market. While it’s still in the early stages, the emerging market has caught the attention of marketers and producers north of the border.

Gas ”Invisibility’

In part, the relative absence of natural gas from the campaign can be chalked up to its “invisibility” for most Mexican consumers, a majority of whom burn liquefied petroleum gas at home, according to Houston-based George Baker, who directs Mexico Energy Intelligence. Power plants and industrial users account for the bulk of Mexico’s natural gas demand, transacting in a market that most voters would not directly take part in.

Nor does gas have the same symbolic and historical weight as oil does in Mexican politics and nationalism.

“Mexico has a national oil narrative, but it doesn’t have a natural gas narrative, so it’s sort of off the radar,” Baker told NGI’s Mexico GPI.

The gas pipeline and local distribution businesses in Mexico have been open to private investment since the mid-1990s. In fact, the ongoing private sector-led buildout of Mexico’s pipeline network began around 2012, before the passage of the present reform, which required a constitutional amendment.

The current administration expects the ongoing liberalization will allow Mexico to develop a dynamic and transparent wholesale gas market for the first time in the history of its energy sector.

Regulators last year issued open access rules for pipelines and implemented a capacity reservation regime separating marketing and transport activities. Price reporting requirements for marketers have also allowed the government to publish proto-indexes showing monthly prices for gas transactions within Mexico. A storage policy published earlier this year mandates the construction of 45 Bcf of strategic underground gas inventories by 2026.

However, the liberalization process is still in its early days. Most, if not all, transactions in the Mexican gas market are priced to indexes in the United States, namely Henry Hub and the Houston Ship Channel. The market has yet to reach a level of liquidity that would allow for the development of local indexes. And while most pipelines in Mexico have launched electronic bulletin boards, a fully functioning secondary market for idle transport capacity has yet to emerge.

Moreover, it is not entirely clear which direction the Mexican gas market is headed in, industry experts said.

“Since Carlos Salinas de Gortari’s privatizations in the 1990s, there has remained a question in Mexico as to how dynamic of markets does the political class and vested interests want,” Padilla said. “Foreign investment is one thing, but the jury remains out on dynamic and liberalized markets.”

As part of the reform, Mexican regulators have applied asymmetric regulations to Pemex to break up its monopoly over the gas marketing business. These measures include an ongoing contract release program to force the state company to relinquish up to 70% of its 3.56 Bcf/d marketing portfolio.

The first phase of the program wrapped up last year, with Pemex ceding 30% of its portfolio to other marketers. Regulators are preparing a second and final phase and currently expect to it to launch in August, a spokesperson for the Comision Reguladora de Energia (CRE) told NGI’s Mexico GPI.

As Pemex’s control over the gas market is dismantled, Mexico’s other state energy giant, power utility Comision Federal de Electricidad (CFE), has emerged as a dominant player. Through its two fuel marketing affiliates, the state company now serves a natural gas client portfolio of around 2.4 Bcf/d. Most are power plants, but they also include some third-party private clients.

State actors thus continue to dominate the gas market. Private shippers hold rights to only 16% of the capacity on the Sistrangas, Mexico’s main pipeline transmission network. The remainder is in the hands of Pemex or CFE and the independent power producers under contract with the utility.

CFE and Pemex hold most of the capacity on the cross-border pipelines into Mexico. The state utility is also the anchor client behind the current buildout of gas transport infrastructure.

Without any specific proposals, it is unclear how AMLO’s administration would steer the development of this fledgling market.

A policy document issued by the AMLO campaign before the election included a pledge to end the asymmetric regulations placed on Pemex. The president-elect has also indicated that he wants the national oil company and the CFE to retain prominent roles in the energy sector.

“It is clear that AMLO believes that both Pemex and the CFE should remain relevant in their respective markets,” Rice University’s Adrian Duhalt told NGI’s Mexico GPI. He is a postdoctoral fellow in Mexico energy studies at Rice’s Baker Institute.

“The CFE’s position in gas commercialization may affect liquidity in the market, but that is probably a price that the AMLO administration could be willing to pay so that the CFE can become a larger natural gas marketer in North America,” Duhalt added. However, “this is just speculation as we do not know that much about AMLO’s stance on gas markets.”

Future of Cenagas

In addition to opening up the marketing segment, the reforms created the Centro Nacional de Control del Gas Natural (Cenagas) to take control of Pemex’s national gas pipeline network in 2016. That system, along with six private pipelines, now forms the 6,256-mile Sistrangas network, which spans the Federal District and 20 of Mexico’s 31 states.

Cenagas acts as the technical operator of the Sistrangas. It also owns and operates the isolated Naco Hermosillo system in Sonora state and administers capacity release auctions for cross-border pipelines on behalf of Pemex and CFE.

Shippers reserved 97% of the 6.13 Bcf/d available on the Sistrangas during an assignation process in 1H2017. That process included an open season during April, in which 24 companies took 2.23 Bcf/d.

The one-year contracts took effect on July 1, 2017, the same day that the capacity reservation regime kicked in. Cenagas has since allowed shippers to renew those contracts and has said it plans to hold a new open season before year’s end.

The operator currently has 43 firm capacity contracts and 24 interruptible service contracts in force. It is also collaborating with Kinder Morgan Inc. to develop Mexico’s first gas trading hub in Monterrey, preparing a project tender to build the first strategic underground storage facility, and coordinating with the private sector on various interconnections and other midstream projects.

The incoming AMLO administration has the power to designate a new director of Cenagas, which is currently led by David Madero. Cenagas also has a six-person board of directors, presided over by the energy minister but with two independent members, that determines its “strategic vision.”

Whether this would put the operator, a relatively young institution, at risk of interference or political meddling is unclear at this stage, but seems unlikely, according to experts.

“Weakening the role of the Cenagas will be detrimental for the security of supply, and that’s something the AMLO administration must take into account,” Duhalt said.

Added Padilla, “Cenagas is probably not one of the most vulnerable entities at this stage given the natural gas balance realities Mexico faces.”

Import Dependency

AMLO’s campaign sketched out plans to reduce the Mexican power grid’s reliance on natural gas by constructing hydroelectric plants. It has also indicated it would continue or even ramp up the current oil-to-gas substitution drive in the power sector, converting older diesel- and fuel oil-fired power plants to natural gas.

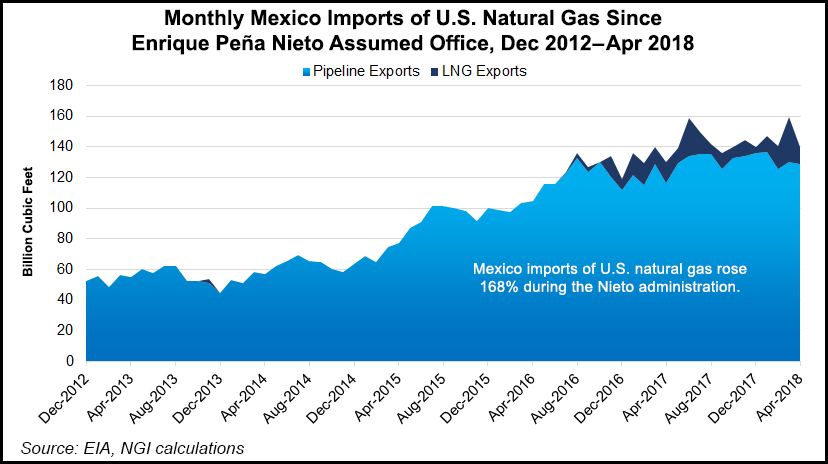

How these proposals will translate to concrete policies remains to be seen. AMLO and his advisers have also said they want to reduce Mexico’s dependence on imported natural gas by reversing domestic production declines.

In a general sense, the latter proposal lines up with the goals of the outgoing administration. The current government has awarded private and foreign E&Ps license to develop blocks in Mexico’s main onshore gas-producing areas, namely the Burgos Basin in the northeast.

To date, very few of these projects have started producing, and Pemex’s dwindling output remains the main source of domestic gas in Mexico.

“Mexico’s massive natural gas deficit will not be eliminated in the foreseeable future and certainly not during the next six years,” Padilla said. “If you want to prioritize domestic natural gas production, you are going to have to create incentives or subsidies in Mexico’s northern non-associated natural gas regions and/or open up bigger onshore blocks, which doesn’t seem to be the focus at least for now.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |