E&P | Markets | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Permian Associated Natural Gas in Early 2020s Could Supply U.S. Demand, Says Bernstein

U.S. natural gas markets are no longer self-correcting as supply surges from onshore unconventional oil-associated wells, particularly the Permian Basin, while demand is maxing out even with exports, according to an analysis by Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. LLC.

Gas price moves are sluggish, and “long periods of low gas prices” are likely if oil prices are constructive to U.S. growth, said Bernstein analyst Jean Ann Salisbury and her colleagues. “We are gas bears and believe that we have seen the end of $3.00/MMBtu gas prices for at least seven years.”

The thesis has three legs. First, demand only can grow as fast as gas exports and it is seen flattening after 2020, despite liquefied natural gas (LNG) export growth and pipelined gas to Mexico.

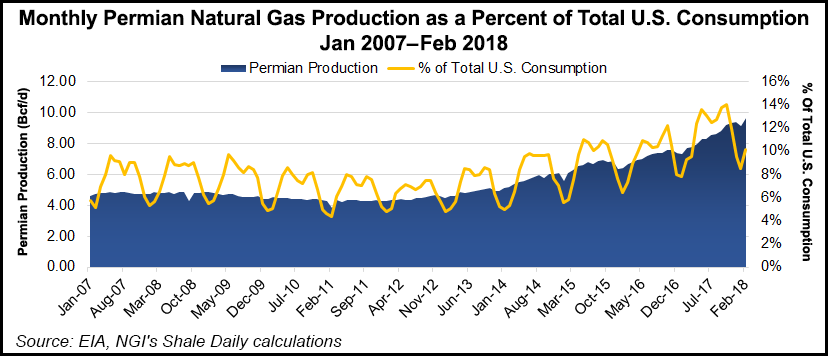

No. 2, associated gas is making up an increasingly larger share of supply, enough to take care of domestic demand for years. The mighty Permian has upended the markets as more efficient oil wells means more “free” gas.

From 2021-2025, associated gas from the Permian alone could meet most domestic demand, “leaving little room for gas-driven basins like the Marcellus or Haynesville,” according to Bernstein.

The third leg of the thesis, the “sunk cost curse,” could spread to Appalachia as more pipeline capacity comes online and exploration and production (E&P) companies fulfill midstream take-or-pay contracts, no matter the price.

The buildout of pipelines in Appalachia may lead Marcellus/Utica players with midstream contracts to produce at price levels that could be “well below the full-cycle cost.” Midstream costs in many basins are running around 50-80 cents for a commodity that’s “worth under $3.00/MMBtu,” Salisbury noted.

“Over the past five years, we have seen that this ”curse’ acts as a weight on gas prices, with many marginal operators producing at less than their fully loaded return price.”

Many onshore E&Ps have renegotiated their midstream contracts in the Barnett, Haynesville and in the Midcontinent plays. However, with limited pipeline capacity, issues have not yet arisen in Appalachia. However, as more capacity comes online, Appalachia E&Ps could face marginal prices for their gas.

The sunk cost thesis is in part based on Bernstein’s medium-term gas outlook for prices to average $2.50/Mcf through 2020 and $2.25 beyond 2020.

E&Ps in high-cost, flat-to-declining basins, such as the Barnett, Fayetteville and Haynesville “are correctly treating the $1.00/Mcf of gathering and local transport costs as sunk,” according to analysts.

That effectively lowers the cost curve of the marginal players “to levels that are competitive with higher quality basins,” which require “full-cycle investments for new gathering and takeaway “and are punished by transport differentials,” such as the Marcellus and Utica.

Meanwhile, significant domestic gas demand was expected to 2020, driven by two things: Mexico’s rising consumption and LNG exports. However, all of the current LNG export capacity in final investment decision stages is scheduled to be online by 2020, and little new capacity is expected before 2025.

The global LNG market now should be over-supplied until 2020, and the expected ramp in exports from Qatar and Mozambique should fill most of the gap through 2025, according to Bernstein.

“This leaves less than 1 Bcf/d of demand for U.S. LNG” after 2020, Salisbury said. “Post 2025, there will likely be more start-ups, but that is unlikely to help for awhile.”

Mexico’s gas potential also is not as big as expected. The country is an 8 Bcf/d market, “and the U.S. is already filling 4.5 Bcf/d of this demand,” Salisbury said. “So, while it may grow, the overall market can only grow so fast, and most of the ”gasification’ is slated to occur by 2020 and then slow down.”

The massive pipeline infrastructure build underway to the Mexico border, estimated at 14 Bcf/d of capacity, “represents far more capacity than imports by Mexico will need, meaning that these pipes will be, on average, 60% full.”

Through 2020, gas demand in Mexico is forecast to grow by 2.5 Bcf/d, and through 2025, demand is estimated at 1.4 Bcf/d, with “no immediate path to much more than this, as gas will represent more than 50% of the power stack at that point.”

The Bernstein thesis isn’t set in stone, as there are threats from lower oil prices and Permian degradation.

“First, we believe that in the low $40s, U.S. oil production would be flat,” Salisbury said. “Gas prices would need to move to $4.00/MMBtu to replace this supply from gas basins. Second, if the average Permian well gets worse, it will open up the space for the gas basins and increase prices.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |