Regulatory | Mexico | NGI All News Access | NGI Mexico GPI | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Monopoly to Dynamic Market ‘Rarely a Smooth Transition,’ Analyst Says of Mexico Energy Reform

A critical assessment of Mexico’s new hydrocarbons industry framework has highlighted milestones and areas for improvement four years into the country’s historic energy reforms.

“Moving from monopolies to a more dynamic market is rarely a smooth transition,” according to the report, “Mexico’s New Hydrocarbons Model: A Critical Assessment Four Years Later” by John Padilla, managing director of energy consultancy IPD Latin America, and Duncan Wood, director of the Mexico Institute at the Wilson Center in Washington, DC.

The full report also explores challenges for Mexican regulators, as well as state oil company Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex).

“In this sense, the reform itself marks a huge step forward,” said the report. “The broad political consensus required for constitutional reform was indeed an impressive achievement that allowed a paradigm shift for Mexico. However, the reform implementation has exposed numerous legal and regulatory issues that need to be addressed.”

The report is based on questions put to participants at forums organized earlier this year in Mexico City, involving a broad swath of industry stakeholders. Based on feedback from those forums, the authors highlighted several strengths of the new hydrocarbons industry model, including the relative speed at which the reforms have been carried out, the institutional framework that emerged, and the interest the changes have elicited from domestic and international investors.

These strengths are particularly apparent in the upstream licensing rounds held over the last three years, according to the report. To date, authorities have awarded 107 exploration and production (E&P) contracts to 73 companies from 20 different countries. These contracts are for onshore areas, as well as offshore acreage in Mexico’s shallow and deepwater basins.

The government has held nine auctions so far, with two more tenders — for onshore conventional and unconventional blocks — penciled in for September.

The growing market power of state-run electricity company Comision Federal de Electricidad (CFE) stands out as a challenge for the natural gas sector in particular.

“The reform has allowed CFE to emerge as a highly dominant and monopolistic natural gas player,” according to the report. Energy regulator Comision Reguladora de Energia “has yet to fully develop and institute policies that will help accelerate greater competition.”

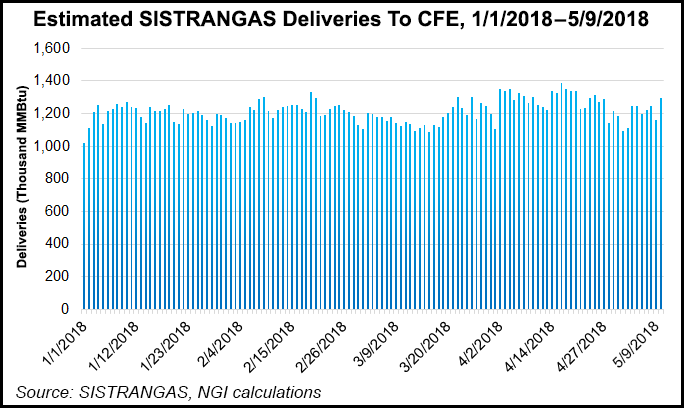

CFE, through its fuel marketing affiliates, has a client portfolio of around 3 Bcf/d. The utility is also the anchor customer for a network of private pipelines being built within Mexico, mainly to supply gas-fired power plants operated by CFE or its independent power producers.

One solution, the authors said, would to be implement asymmetric regulations for CFE, similar to what regulators have done with Pemex.

As part of the reforms, the state oil company’s downstream subsidiary, Pemex Transformacion Industrial (Pemex TRI), is required to relinquish up to 70% of its gas marketing portfolio. Phase 1 of the contract release program wrapped up last year, while a second and final phase is set to begin later this year.

“A fundamental question the Mexican model demands, given how it handled its state-owned monopolies, is how do you create equal access and an even playing field when the monopolies controlled entire value chains,” Padilla told NGI’s Mexico GPI.

“Government officials attempted to do this with Pemex, but did not implement the same principles with the CFE. Those are imperfect questions to solve, but you do need to create a system where third parties are not sidelined from providing a competitive service for the wrong reasons.”

The report also highlights a need to strengthen the gas market’s newly minted independent system operator, the Centro Nacional de Control del Gas Natural (Cenagas). One of several new institutions created by the reforms, Cenagas operates the Sistrangas system, which integrates several privately owned pipelines with a national network formerly in the hands of Pemex.

The state-run agency administers transportation rights on the Sistrangas network and also runs capacity auctions for Mexico’s cross-border pipelines, on behalf of CFE and Pemex. The latter two state companies hold most of the firm transportation rights on Mexico’s import pipelines.

Cenagas “was created to take responsibility for natural gas transportation away from Pemex, and so it is important that this occurs as effectively and efficiently as possible,” Wood told NGI’s Mexico GPI.

“We have looked and cannot find a precedent for an institution such as Cenagas anywhere in the world,” he said. “So first, we are calling for a more complete and nuanced definition of its role: Is it an infrastructure promotion agency, or is it an agency that intervenes in markets? Second, we know that the infrastructure needs of Mexico are huge, so we envision an agency that is better staffed and works hand in hand with operators and investors.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |