Infrastructure | Markets | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Grid-Scale Storage to Wrest Share from Natural Gas in 2020s, Says Raymond James

U.S. natural gas markets have little to fear from battery storage projects for now, but don’t overlook the threat to gas-fired peaking power plants as grid-scale storage is mainstreamed within a few years, according to Raymond James & Associates Inc.

In a note to clients on Monday, analyst Pavel Molchanov said the impact to gas markets from batteries has remained below the radar because storage technology adoption has been slow.

“Beyond the early 2020s, as the cost structure of storage systems declines to levels that make them cost-competitive with gas peakers, there is the likelihood of an exponential increase in storage deployment,” Molchanov said. This will have the effect of reducing the need for gas peakers, putting at risk a sizable portion of the estimated 6 Bcf/d that peakers currently consume.”

Coal suffered a big blow from low-cost and plentiful natural gas. However, the Raymond James team last summer noted that gas has been losing market share on competition from inexpensive wind and solar. And grid-scale power storage is a looming threat.

“Whereas gas has historically played a synergistic role in supporting nonhydro renewables via peaking power plants, that role may eventually become (gulp)…obsolete,” said Molchanov.

Even though power storage is a 2020-plus story, “we have to wonder whether our long-term Henry Hub forecast of $2.75/Mcf is perhaps too optimistic.”

The biggest component of U.S. gas demand is power generation after all. Without its gas demand, the gas glut “would be massively worse,” he said.

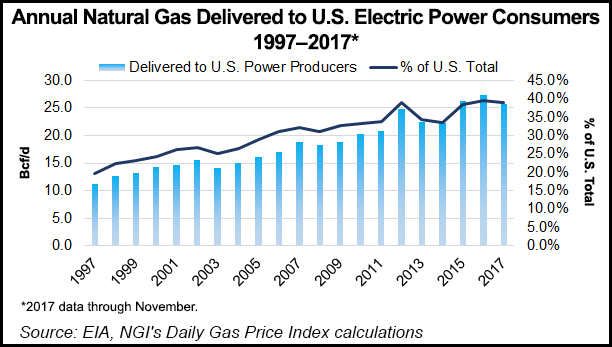

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) export projects and huge petrochemical expansions are taking lots of headline space, but power generation still represents the single biggest component of U.S. gas demand, around 35% of the total share.

“For some perspective, pipeline exports to Mexico and LNG exports combined are currently less than 10%,” said the Raymond James analyst. “As such, it is hard to overestimate the importance of gas share gains in the electricity mix for balancing the gas market.”

For the past decade, power generation added 6.4 Bcfd of gas demand, up 34% or 3% a year. The period from 2007-2012 accounted for nearly all of the uplift: 6.2 Bcf/d.

“During 2012-2017, on the other hand, the increase was a mere 0.2 Bcf/d,” Molchanov noted.

Some weather-related volatility always plays into the coal-versus-gas switching, and the number of coal retirements also varies every year. However, a main reason for the lack of recent share gains by gas has been the surge in nonhydro renewables, mainly wind and solar, he said.

Renewables gained 4.8% of the electricity share from 2012-2017, versus 2.9% during 2007-2012.

That indicates there is “substantially less room for gas to grow,” said Molchanov. As coal’s share continues to decline, Raymond James analyst anticipate that on average two-thirds of the share will be captured by wind/solar and one-third by gas.

“We would also underscore that the growth in wind/solar is entirely newbuild-driven — and therefore fairly predictable — whereas gas is influenced by the pace of newbuilds as well as (in the short run) fuel-switching.”

A rough estimate has about 25% of power sector’s current gas usage specifically for peaking purposes, which equates to around 6 Bcf/d.

“Grid-scale power storage represents a direct threat to peakers, though costs will need to come down by 30%-plus,” said Molchanov. Peakers now play the main role in balancing the grid, “but storage is emerging as a viable substitute” for grid-scale multi-MW storage, not residential products.

Because of the broad range of storage technologies, none in wide use yet, it’s difficult to be precise about economics, he said. However, there is data on the best known technology, lithium-ion batteries.

“Storage systems incorporating these batteries currently have, on average, an all-in (fully installed) cost of $1,200-1,400/KW. Annual cost reductions in recent years have been in the double digits, and conservatively assuming 10% per year, by 2023 the average cost structure should come down to $600-700/KW.”

By then, storage may be “clearly cost-advantaged as compared to combined-cycle gas plants, whose capital cost is generally stable in the range of $900 to $1,000/KW,” Molchanov said.

Very few existing gas peakers would be at risk by 2020, but by 2030, up to half could be, and the pace of newbuilds likely will slow.

As the history of solar has illustrated, “once a new technology reaches the threshold of cost-competitiveness, its scale-up can dramatically accelerate.”

The Raymond James team isn’t arguing that 50 GW of storage would be added over the next seven years, and there are many questions about the pace of the additions. However, the broader point is valid, said Molchanov.

“The silver lining for gas is that policy support for storage remains modest, at least for the time being,” he said. U.S. policy support “is more of a hodge-podge, which reflects the nature of domestic power sector regulation, handled mainly by states rather than Washington.”

For storage, there’s been less of a policy push, which is one reason why technology adoption has been slow. Storage has never qualified for the federal Investment Tax Credit, a subsidy that reduces upfront costs for renewables like solar by 30%.

“To be clear,” said Molchanov, “it is not that policymakers have an ideological aversion to supporting storage; rather, the hurdle seems to be that this issue is too technical or esoteric even for environmentally minded politicians.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |