Regulatory | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Utica Shale

Ohio Regulatory Hurdles Still Delaying NGL Storage Key to Petchem Development

A closely watched project that would be Appalachia’s first to store natural gas liquids (NGL) in underground salt caverns has again been delayed, as it works through a regulatory process that is taking longer than expected in Ohio, where regulators are said to be somewhat unaccustomed to the permit applications.

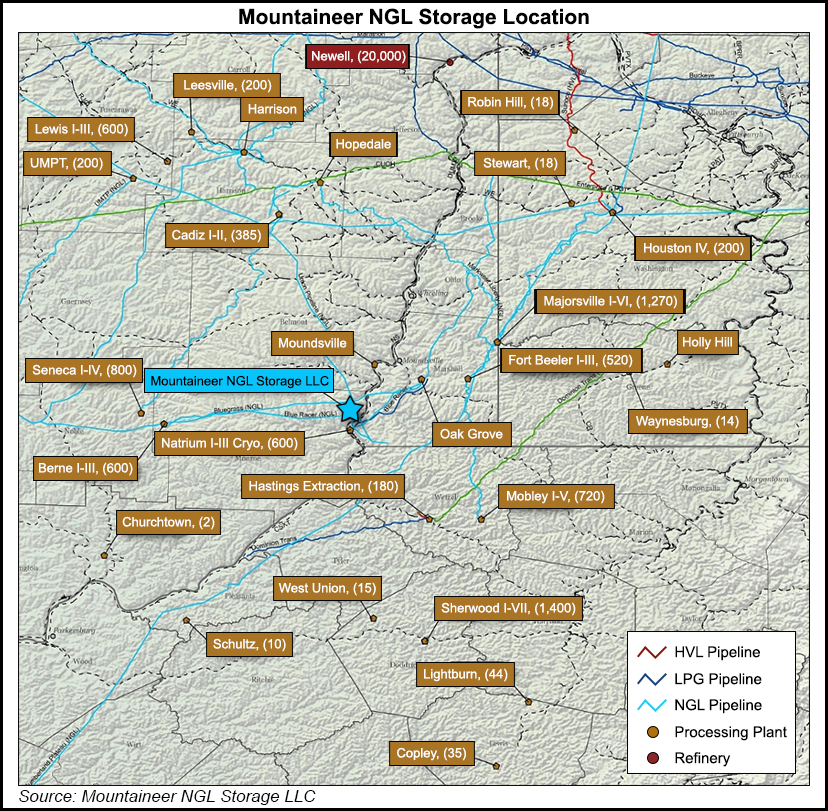

Mountaineer NGL Storage LLC was announced in 2016 with backing from a Goldman, Sachs & Co. investment fund. The company received requests for more than three times its initial planned capacity during a nonbinding open season to store ethane, butane and propane at a site along the Ohio River in Monroe County.

Part of the project was initially expected to be in-service early this year, but startup was pushed to 4Q2018. Mountaineer’s parent, Denver-based Energy Storage Ventures LLC, confirmed that it is now targeting 2019 instead.

“What we’re hearing in the conversations we’ve had with Mountaineer is that they’re having a troubling time moving forward with permits to drill these salt storage wells,” said Thomas Stewart, an Ohio Oil and Gas Association board member. “And we’re concerned about that, we want [regulators] to get it right, but they need to move more expeditiously on the project.”

ESV President David Hooker said regulatory approvals are in fact taking longer than expected. “Ohio does not have regulations specifically designed for NGL storage within one state agency,” he said. “There are regulations governing the construction and operations of this type of underground storage facility, just within the purview of several state agencies that appear to be collaborating on our permits.” Those agencies include Ohio’s Department of Natural Resources (ODNR), Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Transportation.

Mountaineer’s plans call for storage capacity of up to 3.5 million bbl, which could be expanded. Hooker said the company plans to build in two phases. Four caverns in the Salina salt formation, each with capacity of 500,000 bbl, are slated to come online in the first phase sometime next year. The other two or three caverns would enter service later.

Hooker said there are “serious” contract discussions going on with several third parties interested in storing NGLs at the facility, but nothing has been executed yet. In addition to the operational timing concerns of potential customers, Hooker noted that when it comes to contracts, there are the typical “value and capital considerations” of the stored products.

“The issue of storing liquid products is a new concept for this regulatory agency in the state of Ohio, and I think we all recognize that,” Stewart said of ODNR, which oversees oil and gas development and mining in the state. “They’re concerned about migration in a salt cavern; I think they should be concerned about that. But they’ve got to solve the problem is our point. Solve the problem, and let these people move forward.

“The project is needed. If we want the ethane industry, the plastic industry, and all these other projects to move forward, make it happen.”

The Storage Imperative

Additional NGL storage in the Appalachian Basin is seen as key to breathing more life into the region’s petrochemical industry. A unit of Royal Dutch Shell plc is currently building a multi-billion dollar ethane cracker in Western Pennsylvania that’s expected to come online next decade. Four other similar facilities have been proposed for the region, including one by Thailand’s state-owned PTT Global Chemical pcl, which could be close to moving forward in Belmont County, OH.

Proponents of an NGL storage hub want to link up Appalachian shale formations with a network of pipelines, equipment and underground storage. The hub, supporters say, could ease supply and demand imbalances and help create more regional buyers and sellers of the commodities, similar to the one that exists in Mont Belvieu, TX, which sits on a shallower salt dome used to store products.

To be sure, gas storage is nothing new in Ohio or elsewhere in the basin, which has long been a staging ground to move volumes to the Northeast. Salt solution mining has also occurred for decades in the state, and there are currently shallower mined hard rock facilities that store refined products and NGLs in the state and across the basin.

An NGL salt storage cavern, however, is different. It requires a massive brine pond that matches a facility’s capacity. The brine is used to inject and withdraw hydrocarbons to balance pressure deep underground, said West Virginia University’s (WVU) Brian Anderson, who directs the Energy Institute. He played an instrumental role in publishing a study last year that identified a number of limestone, sandstone and salt formations that might be ideal for underground NGL storage in Appalachia.

“That is an additional component of a solution-mined system that is not existing at these other storage locations” in the state, Anderson said of the complexities that come with operating a salt storage cavern.

Hooker also attributed the regulatory delays to Enterprise Products Partners LP’s Todhunter facility in southwest Ohio, a shallower hard rock storage facility that was shut down beginning in 2012 over mechanical integrity issues after a propane leak there. He also said the regulatory woes of the unrelated Rover Pipeline in the state have inadvertently delayed approvals for his company’s project. Hooker added, however, that “impermeable” salt caverns are the “safest most effective means of bulk hydrocarbon storage” that have been in use for decades.

Mountaineer, he said, has spent more than $5 million on technical validation for a test well, core samples, seismic and rock mechanics tests, among other things. Management declined to discuss what regulatory approvals it is still waiting for. Hooker said “we either have, or there is a clear line of sight, on substantially all of our permits. However, we are still working on a couple critical permits with sensitive discussions ongoing with certain Ohio regulatory agencies.”

ODNR, essentially the lead permitting agency, declined to discuss why the process is taking so long. Spokesman Steve Irwin said only that Mountaineer’s application for a Class III solution mining well is pending, with the review of its technical aspects ongoing, and no timeline for completion.

Migration Concerns

“When they undertake those kinds of operations, they’re concerned about the brine being contained, or whether it’s migrating somewhere,” Stewart said of state regulators. “There have been issues up in the Northeast with migration of brine into unsuspected places and a salt solution that’s caused problems in drilling wells somewhere else down the road.”

At about 6,700 feet underground, the Salina is roughly 800 feet below the Marcellus Shale and 900 feet above the Utica Shale. While penetrating various zones during oil and gas well drilling presents normal technical issues, Stewart said producers might also be concerned about migration in the region, which is a hotbed for Utica activity. He stressed, though, that Mountaineer has an economic interest in making its caverns structurally sound and preventing migration. Hooker noted that Mountaineer has designed a state-of-the-art facility, with tests that have validated the salt and confirmed safe cavern operations.

The regulatory delays come as momentum continues to build for petrochemical growth in the basin. Lawmakers from the region have backed federal loan guarantees for underground facilities and urged further study into their feasibility, introducing legislation to help support such initiatives. Both the public and private sectors have also been working closely together on ways to generate more economic growth from the region’s oil and gas boom. Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia have also formed a tri-state coalition to better promote the region’s shale resources.

All of those efforts have stressed the importance of getting more NGL storage installed and operational in the region.

Anderson said the novelty of storing larger quantities of NGLs in different formations shouldn’t cause broader regulatory delays if developers advance similar facilities in other states. Appalachia Development Group LLC, for example, is trying to raise more than $3 billion for a storage hub in West Virginia.

Regulatory requirements in each state, he said, would not be boilerplate. Instead, Anderson said the process “would really be a one-on-one transaction between the permitting agencies in the state and the private sector entity.” Timelines, he added, would likely depend on the specifics of each project.

Last year, Anderson was involved in a Tri-State Shale Coalition meeting at WVU that brought Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia regulators together with those from the Texas Railroad Commission and the Kansas Department of Health and Environment to give the Appalachian agencies a head start on the best practices for regulating more NGL storage.

“They’re not entirely cold on this, we’re at least trying to help get them informed of what’s done in other states that deal with this on a regular basis,” Anderson added of the Appalachian regulatory agencies.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |