Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Provincial Scientists Say Nova Scotia Shale Gas Resources ‘Too Large’ to Dismiss

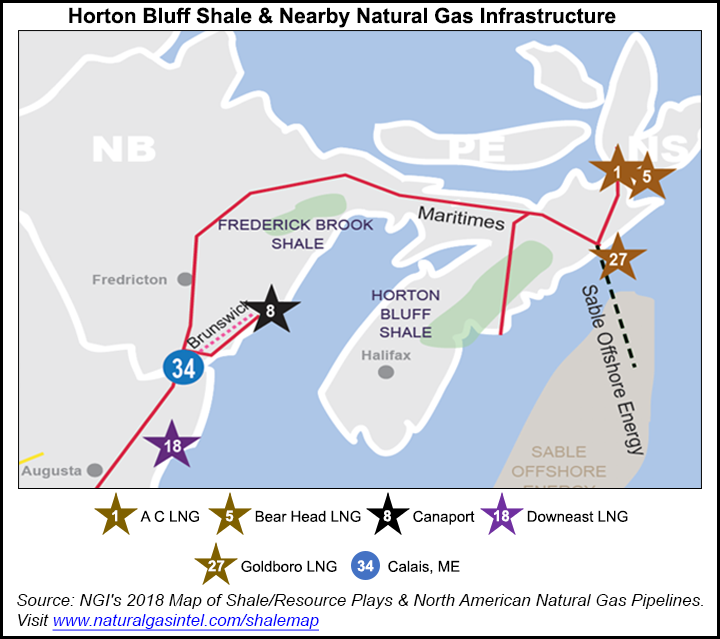

Shale deposits on land, declared off limits to industry in 2014, are rich enough to replace Atlantic Canada’s depleted offshore natural gas production network, says a fresh review by government scientists.

A new Nova Scotia Onshore Petroleum Atlas, by the province’s energy department, predicts banned horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking) could produce 4.3 Tcf of shale gas and 1.5 Tcf from coal seams.

At a realistic price range of US$3.00-9.00/Mcf, Nova Scotia’s recoverable onshore gas resources would eventually yield revenues of $24-73 billion, the latest appraisal said.

The estimates were released at the same time as the fading Sable Offshore Energy Project (SOEP) posted a project description for dismantling its 22 wells, seven production platforms and 204 miles of pipelines starting this year.

An approval decision is due soon from the National Energy Board (NEB) on the first in an anticipated series of switches by Canadian East Coast gas consumers to imports of shale supplies from the United States as replacements for SOEP.

The Dartmouth, NS-based Maritimes Energy Association voiced hope that the new land resources atlas will prompt at least a review of the provincial ban on fracking, saying the report shows shale gas is “too large of an opportunity to dismiss outright.”

The ban was enacted after a provincial inquiry encountered overwhelming popular, environmental, native and academic opposition to the advanced drilling technology – and the Liberal government has not forgotten the results.

While Nova Scotia Energy Minister Geoff MacLellan expressed willingness to hear pro-development views arising from the new atlas, he emphasized the fracking ban stands until the government can be convinced that majority public opinion has changed.

A fracking ban also remains in force with no sign of modification in New Brunswick, where earth sciences appraisals rate the shale gas endowment as a far greater 67 Tcf.

Environmental critics in both provinces remain unimpressed by the geological surveys and prospects of resource development. Release of the new resource atlas prompted immediate counter statements charging that fracking remains a threat to health, water and global efforts to address climate change.

A 2017 report by the Canadian Energy Research Institute, based in the country’s gas industry capital of Calgary, highlighted regulatory and political hurdles faced by shale developers outside provinces accustomed to large-scale production activity.

“The dilemma of unconventional oil and gas development in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia extends beyond the issue of potential adverse impacts on the environment and human health,” CERI reported.

“The possibility of future unconventional resource developments in the two provinces strongly depends on the level of trust the provincial residents have in all levels of government and the industry; clarifying major questions regarding acceptable levels of risk and ways of sharing risk and benefits; and a community involvement in the decision-making process.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |