Pemex’s Revolving Door at Director General Expected to Keep Turning

Mexico’s state-owned oil and natural gas company, Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex), recently appointed Carlos Trevino as its third director general of the six-year administration of President Enrique Pena Nieto.

The question is, how long will he last?

“No longer than Dec. 1 of next year when the next Mexican president names his team for the new administration,” said editor David Shields, who publishes the Energia a Debate magazine. “Anything else would be a huge shock.”

Eyebrows may have been raised in the energy industry when Trevino was appointed, but such short-termism is not unusual at Pemex, where chiefs usually have no previous experience in the oil business. In some cases, the appointees have no business experience whatsoever.

Pemex’s labor union, however, has a very different approach to leadership. Carlos Romero Deschamps recently won unanimous election as general secretary of the Sindicato de Trabajadores Petroleros de la República Mexicana. Romero’s term begins next year and continues until the end of 2024, by which time he will have held the post for 31 years.

Romero’s salary as union leader is about $2,000 a month, at least officially. He and his family have several of the trappings of considerable wealth, not to say ostentation. His son drives a Ferrari special edition, while his daughter has amused her Facebook friends with stories of her travels by private jet, along with her pet dogs, to explore designer stores in European capitals.

Romero himself has a luxurious mansion in Cancun that he describes as a “shack.” Other “shacks” are believed to be located in New York and McAllen, TX, on the border with Mexico.

Accusations of corruption, leveled in the media, have had zero impact on the union boss. As a member of Mexico’s senate, he has immunity from criminal prosecution.

Union members may believe their leader is well worth his apparent wealth. With average wages of about $1,000 a month and generous perks, they are among the best paid of Mexico’s blue-collar workers.

Their position of relative privilege derives from the history of Pemex, which was founded in 1938 from a strike by oil workers of U.S. and British companies that were nationalized by President Lazaro Cardenas.

The nationalization sparked mass jubilation in a nation whose economy was still depressed in the wake of the Mexican Revolution and its subsequent turmoil.

Cardenas and his style of leadership, as well as the one-party system, endured until the end of last century, when Vicente Fox became the first opposition leader to become president of Mexico under what are regarded as the nation’s first free and fair elections.

However, Fox and his successor, Felipe Calderon, were unable to release the Pemex stranglehold of the energy sector. That came later, in 2013-2014, with Pena Nieto’s energy reform.

Pena Nieto, ironically, is a member of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) that ruled for most of last century and defended the state energy monopoly until it took power again in 2012. Now the reform is taking giant steps, although much of the old system remains entrenched with Pemex.

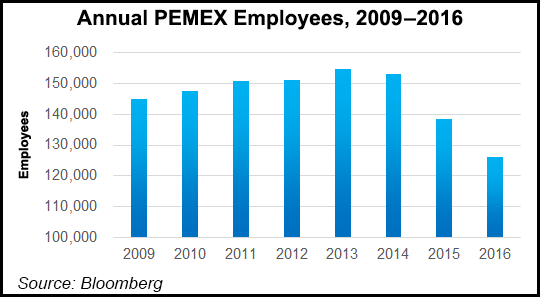

While quarterly losses run into billions of dollars, the workforce is immensely bloated. Even with a 10% reduction between 2012 and 2016, the number of blue- and white-collar workers is about 130,000, including 10,000 doctors and nurses in the Pemex medical services. Productivity levels are about half of those in the majors.

For example, Pemex produced 3.3 million boe in 2015 with a workforce of 46,300, an average of 71.7 b/d. Royal Dutch Shell plc’s upstream division produced 134.2 b/d per worker.

One possible suggestion to the various ills of Pemex has been suggested by Jesus Reyes Heroles, who is a former Mexico energy secretary, ambassador to the United States and Pemex director-general.

Reyes Heroles proposes a sink-or-swim approach. Pemex, he said, should be withdrawn from the federal budget. That would inevitably require a radical restructuring and, almost certainly, an initial public offering (IPO) or some other form of massive capital injection.

The approach has proven to be successful in Brazil, where energy reform took a highly successful “big bang” approach in the form of a $70 billion IPO on Wall Street for Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. (Petrobras) in 2010.

Today, Petrobras continues to shed units by the same means. Last week it raised $1.5 billion from an offering for a fuel distribution unit.

A Mexican big bang, however, was ruled out right from the start of the Pena Nieto administration. The government strongly denied — especially to its followers within the PRI and with moderate left-wing parties — that the reform would amount to the privatization of Pemex, a national icon.

The dilemma posed by Reyes Heroles remains, but Houston-based George Baker, of the consultancy Energia.com, has suggested one possible solution: a “legacy” version of Pemex for domestic purposes and a new Pemex, based in Mexico but financed by Wall Street.

In operational terms, a revamped Pemex would operate throughout the world and in the deepwater of Mexico. Such a move would mirror most of the largest state-owned operators in the world, which have the support of private capital. Many of those operators already operate in Mexico, or are seeking to do so.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 |