Regulatory | LNG | NGI All News Access

LNG Canada Export License Extended, But Still No Sure Thing

An extra five-year lease on life has been given to the last big liquefied natural gas (LNG) export project still standing on the northern Pacific coast of British Columbia (BC), the LNG Canada group led by Royal Dutch Shell plc.

The National Energy Board (NEB) granted a reprieve, until 2027, from the 2022 deadline set by the original export license for exports to start by Shell and Asian partners Korea Gas Corp., PetroChina Corp. and Mitsubishi Corp.

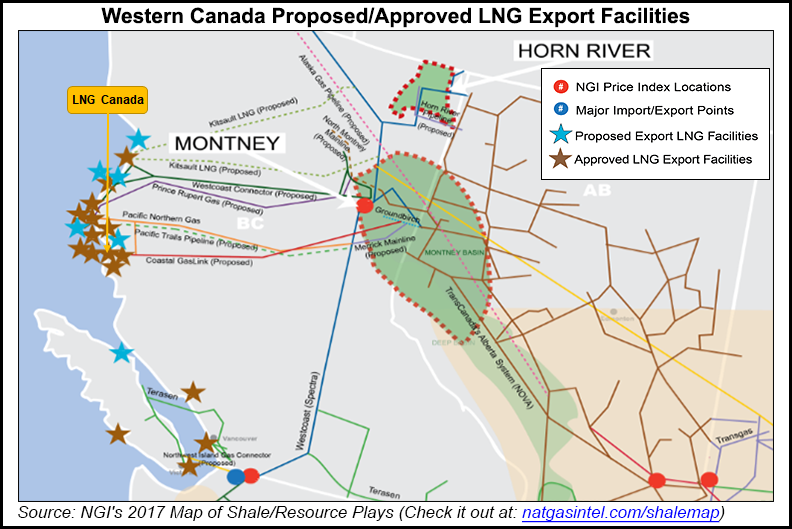

The reprieve also keeps alive the TransCanada Corp. pipeline project Coastal GasLink. LNG Canada commissioned the line in 2012 to relay supplies from Montney Shale gas fields in northeastern BC west 650 kilometers (390 miles) to Kitimat.

Negotiations continue with prospective construction contractors for the terminal. The site would be developed in stages to load overseas tankers with up to 3.7 Bcf/d allowed by a 40-year NEB export license.

TransCanada has estimated a C$4 billion ($3.2 billion) price tag for Coastal GasLink. The line would use jumbo pipe 48 inches in diameter that would start deliveries at 1.7 Bcf/d and be capable of up to 5 Bcf/d by adding as many as eight compressors.

With engineering and contractor bidding still underway, LNG Canada has only disclosed a forecast eventual investment range of C$25-40 billion ($20-32 billion) for all stages in the entire facilities network from wells to tanker docks.

Armed with provincial environmental, route and construction approvals, as well as the federal gas export license, LNG Canada predicted that building the proposed supply network would take five years. Shell’s current schedule calls for a final investment decision and a potential start on the work in 2018.

The date remains only a target.

“Exports might at the earliest commence in summer 2023, though potentially later,” said Shell’s application for the license deadline postponement.

In fact, Shell CEO Ben van Beurden in July gave no signal that LNG Canada was a sure thing.

“We are clearly not at a point that this was considered to be competitive enough when the industry started to change on us,” van Beurden said two months ago during a 2Q2017 conference call. “First of all, do we think we have a project with a breakeven price that is very resilient? This needs to be a project that can of course survive also under downcycles.”

The Canadian export project “has many sorts of fundamental advantages in terms of its feed gas position that is somewhat more stranded than anywhere else in North America and proximity to premium markets etc., but the key thing of course is, do we have the confidence that the capital will come out, where we think we can get it too, having sort of witnessed cost escalation cycles in Canada. That, of course, is big our mind.”

In the granting the deadline reprieve the NEB said, “All of these LNG ventures are competing for a limited global market and face numerous development and construction challenges.” As a result, it said, “Not all LNG export licenses issued by the board will be used or used to the full allowance.”

The decision accepted the project sponsors’ explanation for requesting the deadline extension that “the market for LNG has experienced significant changes” since the export license was originally granted nearly five years ago.

“Global macro-economic factors have influenced a significant increase in natural gas production capacity that has outpaced demand growth in major and emerging LNG import markets,” the application said. “These factors have resulted in persistently low natural gas prices and increased competition among global LNG export projects.”

The Shell reality check was also echoed by an early summer NEB review of overseas gas market conditions that foreshadowed August and September cancellations of two mammoth Asian-sponsored BC projects, Pacific NorthWest LNG and Aurora LNG.

Side effects included leaving a second TransCanada BC project, Prince Rupert Gas Transmission, without a customer and looking for a replacement unsuccessfully to date.

On the changed overseas market of sales and price competition, the board staff report acknowledged Canadian projects face an uphill battle against rivals in the United States. American LNG exporters do not have to build from scratch entire facilities networks from remote wells to northern tanker docks, the NEB noted.

“Canadian LNG projects would generally be greenfield sites and incur higher costs than U.S. projects built on existing LNG import terminal sites,” said the NEB market review. “Most proposed Canadian LNG projects would rely on inland supply sources in northeast British Columbia and Alberta. This would require major new long haul pipelines or expansions of existing systems to transport natural gas to coastal liquefaction facilities — a major additional project expense that also requires regulatory approvals.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |