E&P | Infrastructure | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Regulatory

New York’s NatGas Producers Sent Packing in Shift to ‘Clean Energy’ Economy

*Part three of four. This series examines the effects New York state’s energy policies are having on Appalachian natural gas producers, consumers and the Northeast. It explores the political, operational and economic issues related to the state government’s position on natural gas. Part three looks at what New York’s energy policy has meant for the state economy, local gas producers and the broader industry.

When the oil and natural gas industry was working through one of the worst commodity downturns in decades three years ago, everything came crashing down in New York.

“It’s progressively got worse the last three years. I haven’t been able to take a paycheck out of my company just to keep the doors open. It’s terrible,” said Chautauqua Energy Inc. President Ernest Rammelt, who owns the small exploration and production company in Western New York. “If I hadn’t been in the business 40-some odd years, it would be worse. I’d like to get out now, but you can’t find anyone to buy your reserves.”

In 2014 the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) under former Commissioner Joseph Martens moved forward with a ban on high-volume hydraulic fracturing (fracking). The decision came after nearly seven years of regulatory review and a critical report of the extraction process. The decision was finalized in 2015.

The process started in 2008 under then-Gov. David Paterson, a Democrat who directed the DEC to supplement the state’s 1992 generic environmental impact statement to address fracking. But the industry blames current Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who Rammelt and others believe is pursuing a political agenda that discounts the benefits of natural gas and strongly caters to his liberal Democratic supporters in New York City and college towns like Ithaca.

“All of the sudden, the door was shut,” said Brad Gill, executive director of the Independent Oil and Gas Association of New York (IOGANY). Chesapeake Energy Corp., XTO Energy Inc. and Royal Dutch Shell plc were but a few of the heavyweights to abandon the state after New York’s decision to ban fracking.

“We were left with smaller independents, who cannot make economic sense of drilling the Medina, many of whom have left the state, some of whom have gone bankrupt and others that were thinking of coming to New York, but decided not to because of the hostile legislative and regulatory environment here,” Gill said.

The Cuomo administration did not respond to questions from NGI’s Shale Daily regarding the state’s energy policies.

Rammelt, who also serves as IOGANY’s president, has other businesses in machinery, farming and commercial real estate in New York. But Chautauqua Energy fled. It left behind assets in the Medina formation, which has long driven gas production in the state, to pursue shallow oil assets in northwest Pennsylvania. The company currently operates wells there and has a staff that has dwindled in size over the years from 15 to three people.

The industry continues to battle the state over DEC’s decision to reject water quality certifications for New York-based National Fuel Gas Co.’s Northern Access expansion project and the Constitution Pipeline. Project supporters argue that DEC’s decisions have caused workforce reductions and a loss of income across the supply chain.

Combined, the pipelines would cost more than $1 billion to construct. The companies have estimated that both projects could create nearly 3,000 jobs during construction and hundreds to maintain them after that.

“If these kinds of projects don’t go forward, it impacts the midstream companies, the gatherer, the long-haul company and the producers,” said East Daley Capital’s Justin Carlson, managing director.

But if the effects of New York’s policies on the industry are somewhat clear, what is not are the broader effects on the Upstate’s economy. Many were counting on shale development to spur growth in parts of the state that haven’t seen enough of it.

Upstate Vs. Downstate

The definitions of Upstate and Downstate New York can stoke passionate debates. Generally, though, where the New York City subways stop, Upstate begins. All those areas to the north and west of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority comprise Upstate.

The mere mention of Cuomo’s name at IOGANY’s recent summer meeting in Clymer, NY, brought boos and hisses, but the governor enjoys support throughout the region. Still, other parts of New York share the sentiment of some in the energy industry.

“We are still struggling from the de-industrialization of America,” said Unshackle Upstate Executive Director Greg Biryla, who oversees a coalition of business and trade organizations from the region. “We haven’t finished the job of replacing our manufacturing sector with other industry. Upstate New York is just very different when it comes to those challenges of taxes, regulations, mandates — they’re just felt that much more.”

There are bright spots for the region’s economy, but Biryla’s argument recalls the slow bleed of Eastman Kodak Co.’s workforce in Rochester over the years, and the thousands of jobs eliminated in Buffalo by the now defunct Bethlehem Steel Corp. in the 1980s.

Allowing high-volume hydraulic fracking“would have been the single best rejuvenation of that economy that could have occurred — more so than any state investment or program,” Biryla said.

To be sure, Cuomo has focused intently on the Upstate, investing more than $25 billion to revitalize the region, according to the administration. Under Cuomo’s Reforming the Energy Vision program, renewable energy generation would increase to 50% by 2030. After the United States withdrew from the Paris Agreement, Cuomo announced a plan to grow the state’s emerging “clean” energy economy and prepare the workforce with a $1.5 billion investment for renewable projects.

Under Cuomo, the state’s economy has added more than one million private sector jobs and experienced employment growth in 67 of the last 79 months, the New York State Department of Labor said in August.

However, Biryla and some of his colleagues claim that growth has been disparate. New York City, he said, is a “world unto itself” that has consistently demonstrated the ability to defy both micro and macroeconomic trends.

According to the Brookings Institute Metro Monitor, which tracks the economic performance of the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas, places like Rochester and Buffalo rank among some of the lowest. Job growth has been sluggish in the Buffalo, Binghamton and Rochester areas in the last two years. Ithaca area employment has trended upward during the same time, as it has in the state capital Albany.

Cornell University and Ithaca College, considered bastions of anti-fossil fuel sentiment, have generated strong private sector employment. While the private sector has grown in Albany, state government also factors heavily into its economic well-being.

“It comes as a shock to me in the sense that every politician in every party talks about the need to bring back manufacturing,” Biryla said. “The one constant is that manufacturing uses a lot of energy and by stifling development of these natural gas pipelines, we are limiting the ability to get affordable natural gas and affordable energy to manufacturers.”

New York residential customers paid 40% more than the national average for electricity last year, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration and NGI calculations. Commercial users paid nearly as much, or 39.5% more. Industrial electricity customers and residential natural gas consumers, however, pay roughly 10% less than the national average.

Biryla believes more natural gas could help stem Upstate population, tax and business loss, as do other business leaders who have argued for more inclusive energy policies.

No Medina Revival

A local gunsmith drilled one of the country’s first commercial natural gas wells in Western New York’s Chautauqua County in 1821. The Hart well reached a depth of 27 feet into shale that outcropped in the area. Sixty-two years later, gas from sandstone reservoirs in the Medina formation was discovered. By the mid-20th century, demand outpaced New York supply.

“The Medina will never come back unless the price gets up to $4.00 or $5.00/Mcf,” Rammelt said.

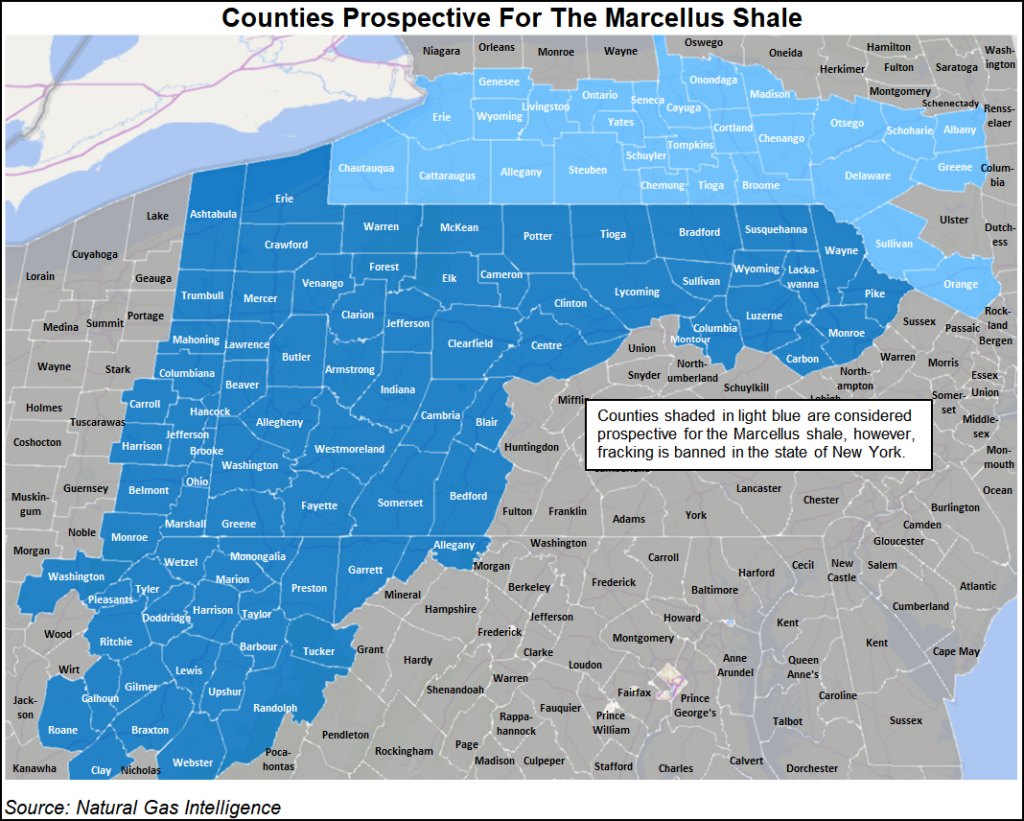

New York’s producers had long hoped to tap into what was once stranded natural gas in the Marcellus Shale. IOGANY’s Gill met with Cuomo in May 2012 and liked what he heard. Later that summer, a five-county pilot program was floated by the state in which 150 unconventional wells would be permitted by 2014 in the Southern Tier’s Broome, Chemung, Chenango, Tioga and Steuben counties — localities that supported drilling.

The hope for an industry revival was dashed two years later by the fracking ban. “It’s very disappointing. New York, for decades, has been comprised of conventional operators,” Gill said. “The light at the end of the tunnel was back in the early 2000s, when the unconventional plays came about and we had the prospect of exploring for Marcellus in New York.”

Political science professor Robert Shum of the College at Brockport in Upstate said the industry itself has been part of the problem.

From the natural gas industry’s point of view, “it’s easy to point fingers at Cuomo and say, ”he’s being a political opportunist; he’s just pandering to the extreme environmental left,’” Shum said. “I think the industry tendency might be to overstate it and not ask hard questions of itself in terms of why it has not been able to mobilize support for its projects and do things like they have in other states where they rallied local communities.”

Shum said there was a serious opportunity for operators to conduct horizontal drilling in the Southern Tier. At the time, however, the debate over its advantages and disadvantages was not as “vibrant” or “substantive” as it was in other states, which he said is partly to blame on the industry.

“The main thing is to go back to fracking,” he said. “Cuomo didn’t make promises in terms of putting a ban on fracking. He said we need to study it more. The gas industry lost because they couldn’t mobilize; maybe they underestimated the environmentalists.”

Gill and others still hope that President Trump might intervene to get pipeline projects in the state going again. But since the fracking ban, Gill has warned the industry to “take your opponent seriously” and to be funded for the battles ahead.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |