Infrastructure | Markets | NGI All News Access | Regulatory

NatGas, Power Grids Coast-to-Coast Perform As Expected in Midst of Solar Eclipse

The “Great American Eclipse” happened as forecast Monday, and the nation’s natural gas and electricity grids didn’t even blink.

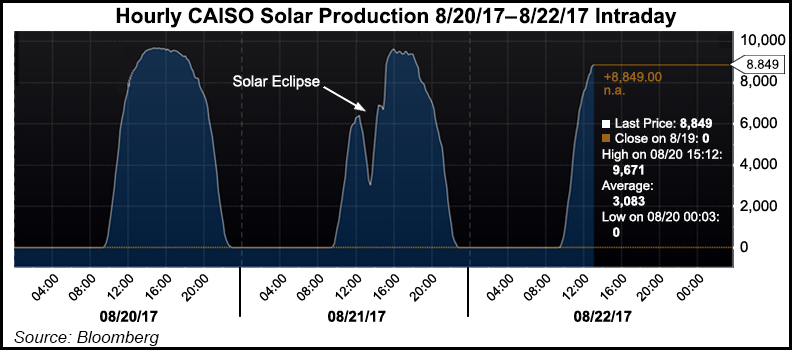

In California where the grid operator manages more solar power than anywhere in the country, supplies from the sun plummeted by more than 3,000 MW when the total eclipse first hit the West Coast and then just as quickly spiked upward an hour later, according to the California Independent System Operator’s (CAISO) real-time data. CAISO’s website tracks renewables 24/7.

With millions of Americans viewing the celestial show in a 70-mile swatch spanning from Oregon to South Carolina, scientists and grid operators who prepared for months in advance for the event now will be calculating and analyzing what it foreshadows for energy planners and astrophysicists alike. CAISO engineers began Tuesday to deconstruct the eclipse and expect to have some observations and numbers in a few days, a spokesperson told NGI.

CAISO had forecast a drop of 4,200 MW worth of utility-scale solar on its grid, but the actual drop was closer to 3,500 MW, the spokesperson said. Why it was less is one of the questions being analyzed, he said. “It is going to take a few days to actually crunch numbers; for now, we just have a few observations.”

One fact is clear: natural gas-fired generators and hydroelectric power filled the gap in California. Gas-fired capacity makes up more than half of the 70,000 MW available to CAISO.

Generally, operations on Monday “went very smooth; more smooth than what was expected,” the CAISO spokesperson said. “We had no major issues and no minor issues, it was extraordinarily smooth and we attribute that to the advance outreach, conference calls and coordination that we had for the past several months with market participants.”

CAISO officials were satisfied there was no impact from the eclipse to the state’s bulk electric system, and that was the story that unfolded for the most part throughout the nation. CAISO expects that a definitive list of “lessons learned” may take some time.

“Exactly what we come up with and how we disseminate it is not determined at this time,” the CAISO spokesperson said.

In Idaho, Idaho Power Co. reporting “smoother-than-normal” grid operations where up to 280 MW of solar on its grid dropped to zero or near-zero during the eclipse, but the loss was made up by other sources, mostly hydro.

“Our grid operators said it was actually easier during the eclipse than normal days because the pattern of solar energy was more certain; with the eclipse we knew exactly when it was going to start and how long it was going to last,” a utility spokesperson said.

On the East Coast, Charlotte, NC-based Duke Energy Corp. said it lost about 1,700 MW of solar capacity during the eclipse’s peak.

“Given the weather conditions, we should have expected 1,808 MW of solar output during the afternoon. But at the height of the eclipse, we were getting only about 109 MW,” Duke management said. Duke has about 2,500 MW of installed solar capacity in North Carolina, the nation’s second largest solar state behind California.

“We were able to balance the Duke Energy system to compensate for the loss of solar power over the eclipse period,” said Director of System Operations Sammy Roberts. “Our system reacted as planned, and we were able to reliably and efficiently meet the energy demands of our customers in the Carolinas.”

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) service area was in the path of totality, and the Southeast utility saw about 30% less generation from its renewable sources Monday than it was expecting the day after the eclipse, according to spokesman Jim Hopson. He said TVA has close to 500 MW of solar capacity between utility-scale and distributed sources.

“It was a significant decline over the course of the day,” Hopson said. “You were reducing solar intake for the better part of three hours both going into the eclipse and coming out of the eclipse. It was a significant loss of solar power for what is traditionally one of the peak periods for solar in our area.”

TVA made up for the declines in solar through a combination of natural gas, nuclear, coal and hydroelectric generation, according to Hopson.

As a result of the eclipse, PJM Interconnection saw a decline of around 520 MW in wholesale solar generation across its large footprint in the Mid-Atlantic and parts of the Midwest. The grid operator estimated that behind-the-meter solar generation decreased by about 1,700 MW. Solar makes up less than 1% of PJM’s 185,000 MW of generation capacity.

“PJM had expected a reduction in power demand from rooftop panels to result in an increase in electric demand on the grid,” the operator said. “However, because of a variety of potential factors, including reduced air conditioning, increased cloud cover and changes in human behavior related to the event, PJM saw a net decrease in demand for electricity of about 5,000 MW throughout the eclipse.

“The PJM footprint experienced an average temperature decrease of about 2 degrees Fahrenheit through the duration of the eclipse. The Chicago area also experienced storms after the eclipse’s onset.”

Richmond, VA-based Dominion Energy spokesman Rayhan Daudani said the utility saw minimal impact from the eclipse. During the eclipse’s peak over Virginia, solar output briefly dropped by around 90%, he said.

“While the Aug. 21 eclipse caused our solar output to drop briefly, Dominion Energy customers did not feel any impact,” Daudani said. “We had analyzed several scenarios and consulted with other industry experts to ensure we were prepared for any effects. Our diversified energy mix ensured there was no impact to our customers and we were able to continue to offer the same reliable energy as we do on any day.”

The North American Electric Reliability Corp. (NERC) earlier this year published a white paper on the eclipse, drawing on an assessment of the 2015 solar eclipse in Europe and concluding that the more diversity of power sources on the grid, the more impact an eclipse can have. The overall amount of solar on the North American grid had grown in 2016 to 42,619 MW from 5 MW in 2000 with a large portion of it centered in California.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |