Markets | Infrastructure | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Regulatory

Recent Declines Underscore ‘Choppiness’ of NatGas Power Burn Outlook, Say Analysts

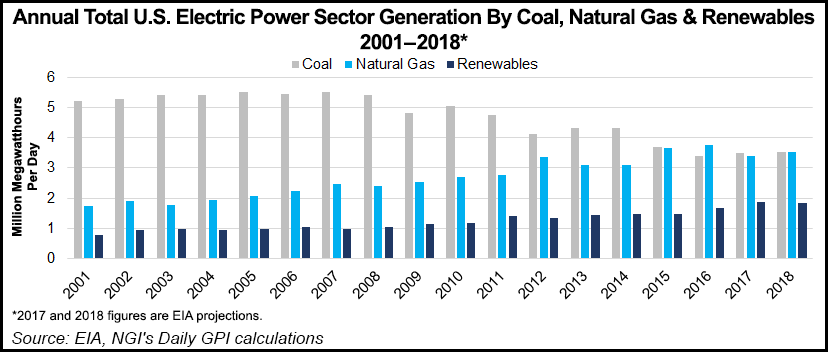

Natural gas is on track this year to see the largest drop in its share of U.S. electric generation in over a decade, highlighting the price sensitivity of power burn as gas competes with renewables in the years to come, according to an analysis by Raymond James & Associates.

Analysts J. Marshall Adkins and Pavel Molchanov said in a research note Monday strong Henry Hub prices in the first half of 2017 helped coal gain back domestic electric generation market share from gas. But the firm is forecasting Henry Hub prices to average $2.75/Mcf in 2018, which could see coal give back most of its 2017 gains.

In the long-term, amid limited growth in total U.S. electric demand, “coal has more room to fall, with gas and wind/solar competing for the spoils.” But while previous estimates were for gas and renewables to divide up coal’s vacated market share roughly 50/50, the analysts said they now expect wind/solar to replace as much as two-thirds of coal’s declines over the next decade.

“Conventional wisdom is that natural gas and nonhydro renewables will both be long-term winners in the U.S. electricity mix. In this case we think that the conventional wisdom is directionally correct,” they wrote. “However, the choppiness of gas’s market share should not be overlooked. Gas’s share of the U.S. power generation market will remain highly sensitive to the interplay of gas versus coal prices.” The declines in 2017 provide “a clear-cut illustration of gas temporarily losing share to coal.”

Power burn is likely to recover in 2018 and beyond, “but it will have to contend with increasingly potent competition from wind and solar. While we believe overall U.S. gas demand growth will be strong…energy investors may be overly optimistic about gas’s long-term share gains in U.S. power generation.”

Recent newbuild numbers have heavily favored wind and solar compared to natural gas, according to Adkins and Molchanov, with the renewables accounting for two-thirds of nameplate capacity added in 2016.

“Because typical capacity factors are lower for wind and (especially) solar” versus gas and coal, “for wind and solar to gain two-thirds of the incremental share their associated newbuilds would have to make up around 80-85% of total newbuilds,” the analysts said. “That is certainly on the aggressive side but not out of the question.

“The fact of the matter…is that the all-in economics of new wind (and increasingly solar) projects — driven by a combination of lower-cost hardware, lower installation costs and increasing operating efficiency — are improving at a faster pace than the cost of new gas-fired generation capacity.”

After 2020, grid-scale batteries could become more affordable as well, addressing the intermittency issues for wind and solar, they said.

The analysts expect wind and solar newbuilds to accelerate over the next few years to take advantage of investment tax credits (ITC) and production tax credits (PTC) that begin to expire after 2019. The 2017 pace of 12-14 GW of solar and 8-9 GW of wind will likely increase through the end of the decade, the firm said.

“To be clear, this does not mean that the ITC and PTC are necessary for economic viability. In fact, NextEra, the largest U.S. wind generator, predicts that wind will become the lowest-cost source of U.S. electricity by 2020, with solar and gas tied not far behind,” Adkins and Molchanov wrote. “Even though the tax credits are increasingly not needed for wind power economic viability, the tax credits create ”bonus’ uplift for project economics. That means there are plenty of utility-scale wind and solar installations that will be deliberately accelerated in order to get in ahead of the tax expirations.”

As for coal, “to point out what should be obvious, the recent recovery in U.S. coal-fired generation has nothing to do with the regulatory landscape under the Trump administration,” the analysts said, calling the changes from the White House more “rhetorical” than “substantive.”

Politics aside, coal’s 2017 gains have come from higher utilization rates of assets in place and not from long-term investments. “U.S. coal-fired power plants are still shutting down. At least 9.4 GW of coal shutdowns (4% of total coal-fired capacity) were announced in the first half of 2017 — and this is occurring regardless of what ultimately happens” with government efforts to curb climate change, according to Adkins and Molchanov.

“This compares to a mere 0.9 GW” of coal-fired capacity “that’s in development, none of which is actually in construction.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |