E&P | LNG | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Gulf Coast Could See Renewed Storm-Related Volatility As LNG Exports Grow, But It Won’t Be Armageddon

It’s been 12 long, relatively quiet years since Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, which at their highest intensity both ranked as Category 5 storms, washed across the U.S. Gulf of Mexico (GOM) and destroyed natural gas and platforms and onshore infrastructure.

The 2005 storms shut in 21.5%, or 784.5 Bcf, of the GOM’s annual natural gas production (3.65 Tcf) and 29.67%, or 162.4 million bbl, of its annual oil production (547.5 million bbl), according to the final report from the U.S. Department of Interior’s predecessor Minerals Management Service (MMS), which at the time managed energy resources on the Outer Continental Shelf.

Almost a year after the storm, on June 1, 2006, about 1.099 Bcf/d of gas production, then equivalent to 10.99% of the daily output in the GOM (10 Bcf/d), remained shut in. Shut-in oil production on that day stood at 227,888 b/d, equivalent at the time to 15.19% of the GOM’s daily oil output (1.5 million b/d).

Around the storms, which included other devastating storms, including Hurricane Dennis that 2005 summer, natural gas and oil markets reached then-record levels, with New York Mercantile Exchange gas futures surging above $13 and oil prices rising above $70. And with Henry Hub declaring a force majeure during the twin storms, NGI was unable to publish a daily index at the benchmark gas hub for several days.

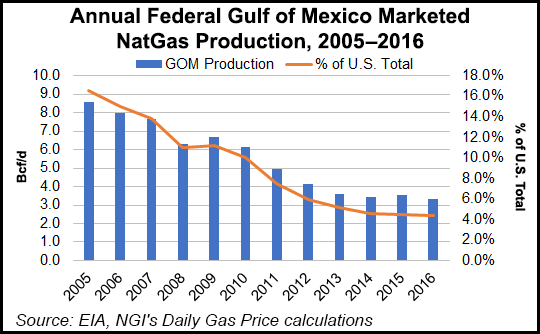

A lot has changed in a dozen years. GOM natural gas production today represents only a fraction (5%) of total U.S. output, compared to around 20% in 2005, as most of the vast US. supplies now reside onshore thanks to the unconventional drilling revolution.

Now, when hurricanes make their way into GOM waters, gas markets respond with a swing to the downside as storms and the rains they bring with them cause more destruction to demand than to production. Still, any volatility in the gas markets is rather limited in comparison to the wild upswings the market experienced in 2005.

That could change, however, as the Gulf Coast is now home to a vast network of liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals that are expected to export close to 8 Bcf/d by 2020. There also is a host of other large gas-consuming facilities, including petrochemical newbuilds and expansions, in place or underway along the Gulf Coast.

The largest of those LNG export terminals is Cheniere Energy Inc.’s Sabine Pass, which, when the first five of six trains are in operation by the end of 2019, would export up to 3 Bcf/d. Cheniere is also building an LNG export facility in South Texas in Corpus Christi, designed to export up to 1.2 Bcf/d. Cameron LNG and Freeport LNG would add another 3.65 Bcf/d of combined export capacity along the Gulf Coast. There are other LNG projects also in the works to be sited along the Texas and Louisiana coastlines.

“Since the days of Hurricane Katrina, the structure of the North American gas industry has changed tremendously,” said Berkeley Research’s Chris Goncalves, chair and managing director of energy. “Onshore shale gas production has supplanted huge volumes of offshore conventional production on the supply side, and on the demand side, there is a lot of new infrastructure that has been built to process gas and gas liquids, and facilities that consume natural gas in order to produce petrochemicals.

“Similarly, with LNG exports, the industry is building major feed gas consuming facilities. So, as compared to the days of Katrina, supply is much more insulated, but there could be a significant reduction in demand due to a hurricane.”

Damage to LNG facilities is perhaps the largest potential market mover if a major storm were to make landfall along the Gulf Coast. Also, getting ships into and out of berths, as well as outages that could affect connecting pipelines, could produce secondary impacts that also could create some volatility in the market, he said.

Black & Veatch’s principal consultant Denny Yeung agreed that if ships were unable to load cargoes, it would have a ripple effect on the flow of gas into the Gulf Coast LNG export terminals. The LNG export terminals would have to alter their upstream gas supply purchases across a variety of supply basins and/or find alternative storage services to inject the gas into storage.

“This market demand shift could lead to increased regional price volatility as nearly 10 Bcf/d of supply could be redistributed across the North American market,” Yeung said.

BTU Analytics energy analyst Jason Slingsby said demand destruction would only become more amplified by increasing LNG exports over the next few years.

“In the fall during the peak of hurricane season, BTU forecasts LNG exports in 2021 near 6 Bcf/d, but infrastructure could theoretically flow as high as 8-10 Bcf/d by then,” Slingsby said. “With a total demand market around ~85 Bcf/d, this could result in a 5-10% move downward in demand if a significant storm were to hit.”

The pressure on demand would cause volatility in the gas markets and could send Henry Hub prices significantly lower, he said. But, given that LNG exports are expected to be sourced from various regions across the United States by the time the Gulf Coast’s LNG export business is fully built out, basis blowouts would likely not occur and recovery would happen fairly quickly.

“If the hurricane didn’t cause any lasting damage, recovery would likely happen pretty quickly,” Slingsby said.

Goncalves agreed, saying the ability of LNG facilities to manage outages would help the market recover quickly.

“Even though you will have all this LNG infrastructure built out along the Gulf Coast, hurricanes won’t hit all those areas at once,” said the Berkeley Research chair. “So, while some facilities may come out of service, others may remain in operation. As major consumers of natural gas, they are spread around geographically. There are concentrations around Louisiana, the Houston Ship Channel and southern Gulf Coast, but they won’t be all taken out at once”.

In terms of managing short-term solutions, things need to happen from a commercial perspective to manage outages, but those are feasible avenues producers can take, Goncalves said. The same would be true in the natural gas liquids and petrochemicals industries. For example, customers could buy replacement cargoes from other facilities that are still in operation, such that reduced production in one region because of a storm could be managed through increased output in another region through commercial transactions.

Indeed, while the majority of storms that sweep across the Gulf Coast would not be Armageddon, the fall of 2005 may have felt like it for the oil and gas industry. In May 2006, eight months after Rita made landfall west of the Texas-Louisiana border, the MMS dramatically increased the number of pipelines listed as damaged by Katrina and Rita to 457 from 183 based on additional industry assessments and investigations. (MMS duties now are handled by Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE).)

MMS in its 2006 assessment also raised the number of damaged large diameter pipelines (10 inches in diameter or larger) to 101 from 64 while lowering the number of platforms destroyed to 113 from 115.

With a host of Gulf Coast petrochemical projects being planned or under study over the next five years and more LNG exports on the way, the region is reclaiming some of the gassy spotlight that had been on the Marcellus Shale.

“This all does bring prominence back to the (Henry) Hub due to the new demand that will come from LNG and the bigger facilities that are located in the Gulf compared to Elba and Dominion Cove Point on the East Coast,” said Genscape Inc. LNG analyst Jason Lord.

A similar scenario this year could wreak havoc on U.S. gas markets, but it could also extend into the global LNG market if the timing were right. The impact of a temporary supply disruption in North America would be muted on a global scale, Yeung said, as tropical storms or hurricanes would most likely occur during the late summer months, when Asian and European market demand is lower.

“But depending on the duration and damage from a tropical storm or hurricane, it may have a more significant impact on global LNG prices if the supply disruption reached into the early winter months,” Yeung said.

As Goncalves noted, weather considerations are no surprise to the operators that own facilities along the Gulf Coast. “You have to consider these events when building out facilities,” he said.

Cheniere is no different. Its facilities are capable of withstanding 150 mph sustained winds, gusts of up to 180 mph and maximum storm surges, according to spokesman Eben Burnham-Snyder. In fact, a lot of the facilities and equipment are built on stilts. On June 22, when Tropical Storm Cindy made an almost direct hit on Cheniere’s Sabine Pass Terminal, the company had no major disruptions.

“Some ships spent a little time rocking back and forth in the waves. But as far as getting exports off, we had no problems with that,” Burnham-Snyder said.

Genscape’s Lord said while there was some delay in ship loadings at Sabine Pass, the facility had tank capacity available to continue to liquefy. Still, there was a buildup of ships in the GOM after the storm.

“Depending on the facility’s storage levels and severity of the storm, they may continue to liquefy (like Sabine did) but hold off on ship loadings. In the case of a severe storm, facilities may stop ship loadings and liquefaction altogether and declare force majeure,” Lord said.

If Cheniere were to declare a force majeure at any of its facilities, the company has business interruption insurance that would cover the loss of income the company may suffer due to the closing of facilities or due to the rebuilding process.

As with any approaching storm, however, facilities across the region take the necessary steps to ensure the safety of their employees. Two days before Tropical Storm Cindy made landfall on June 22, Royal Dutch Shell plc said it had taken precautionary steps to secure its assets in the GOM.

“Personnel will remain offshore and we have suspended all offshore flights from heliports located in Central Louisiana. Some well operations have been suspended and production is currently unaffected,” the company said.

Likewise, BP plc said that non-essential personnel had been evacuated from its platforms without impacts to production. Anadarko Petroleum Corp. removed non-essential personnel from its GOM facilities as a precautionary measure.

On the morning of the storm, the BSEE said personnel remained evacuated from 39 production platforms — 5.3% of the 737 manned platforms in the GOM — and from one rig. No rigs were moved off location out of the storm’s path.

Only a fraction of GOM natural gas (440 MMcf/d) was shut-in, according to federal officials. Due to a loss of remote platform communications at at Main Pass (MP) 260 platform, Destin Pipeline declared a force majeure, and it remained unable to provide gas transportation service from all of its offshore receipt points.

But while Cindy had an overall limited impact on GOM operations, other storms like Katrina and Rita that cause widespread flooding could not only hinder current operations but also delay projects that are still in the process of being constructed.

Cheniere continues to work to bring online Trains 4 and 5 of its Sabine Pass facility, but Burnham-Snyder said potential weather delays are already included in the company’s project timelines, and it would be too difficult to say how a hypothetical storm and a hypothetical impact would affect those timelines.

“I would say we have delivered so far three trains on time or ahead of schedule and under budget. So, we have a track record no matter what weather or other external forces happen, we have delivered on what we say we’re going to do and have even exceeded expectations,” he said.

Cheniere also has a dedicated meteorologist on staff that is part of the company’s core planning, both for designing facilities and managing day-to-day operations.

“You do have to stay humble when it comes to Mother Nature,” Burnham-Snyder said.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |