E&P | LNG | M&A | Mexico | NGI All News Access | NGI Mexico GPI | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Mexico Natural Gas Production Declines; Pipeline Issues Could Spell Summer Shortages

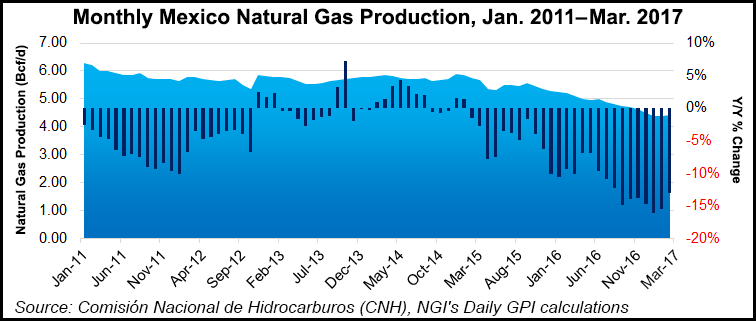

As temperatures rise in what promises to be a hot summer in Mexico, the country’s production of natural gas — the fuel of choice for the nation’s power plants — has been dropping by 10% year-on-year in recent months.

To make matters worse, the Los Ramones pipeline project is facing problems. In theory, the third and last phase of Los Ramones should be transporting 1.3 Bcf/d of gas from the Texas shale fields into central Mexico, but industry sources say there has been a substantial shortfall.

“My understanding is that Los Ramones has been running at only about a third of its capacity,” said Luis Miguel Labardini, a partner of the Mexico City-based Marcos y Asociados consultancy.

Mexican newspapers have claimed that Cenagas, the Mexican regulator, is planning to sue France-based Engie, which built the third and final stretch of Los Ramones. But Cenagas Director General David Madero denies that.

“There’s been a problem with Los Ramones, but it’s being resolved and Los Ramones is close to full capacity,” Madero told NGI. Nor is there any question of anyone being sued, he added.

Meanwhile, Arturo Carranza of Mexico’s National Institute of Public Administration said the potential natural gas shortage is larger than Los Ramones. “Bringing a legal suit over Los Ramones would not in any case resolve the problems faced by the shortages of gas, and these have been emerging in and around Monterrey,” he told NGI.

Monterrey is Mexico’s northern industrial capital. In addition to industrial might, Monterrey is one of the nation’s most prosperous cities and one with blistering hot summers, where all but the very poor have air-conditioning at home.

The middle classes in Mexico’s arid regions and along the coasts mostly use air-conditioning. The central plateau, which accounts for the greater metropolitan area of Mexico City, has a temperate climate, and only a few of its 20-25 million inhabitants use air-conditioning at home.

The immediate remedy for the recent shortages of natural gas, said Carranza, is to import more liquefied natural gas (LNG) via Mexico’s three terminals.

The three are Altamira on the nation’s northern Gulf Coast, where a unit of Royal Dutch Shell plc is the importer; Sempra Energy’s Energia Costa Azul near Ensenada in Baja California; and Manzanillo, Mexico’s leading Pacific Coast seaport where the LNG terminal is owned and operated by state power utility CFE.

CFE was supplied at Manzanillo by Spain’s Repsol SA under a long-term contract from Camisea in Peru. The contract has now been taken over by Shell under its takeover of Repsol’s LNG business.

“But buying LNG is an expensive business,” said Carranza, “and the government’s finances are not very healthy at the moment.”

On top of that, he adds, CFE is under pressure to keep tariffs down as much as possible, with key gubernatorial elections very soon and the launch of presidential campaigning due later this year. Indeed, the presidential race already has a front runner in the shape of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, an opponent of energy reform and a fierce critic of market-led energy prices.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |