Infrastructure | NGI All News Access

NatGas/Renewables in 2016 Drove Largest Electric Generating Capacity Increase in Years

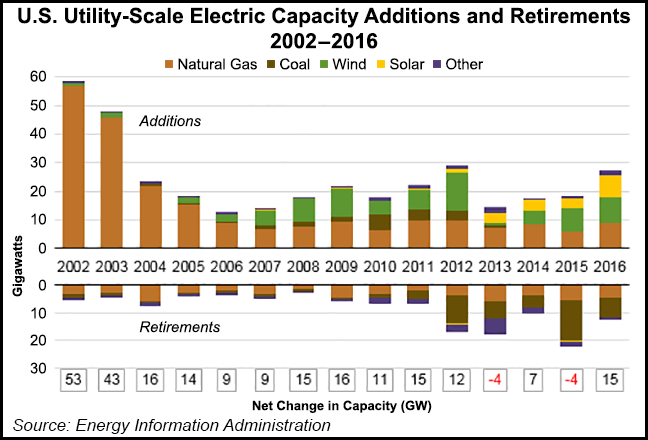

Driven by natural gas and renewables, the U.S. power grid added more than 27 GW of electricity generating capacity last year, the largest amount added since 2012, the Energy Information Administration (EIA) said Monday in a Today in Energy note.

EIA said the additions more than offset the retirement of about 12 GW of capacity, which resulted in a net gain of nearly 15 GW. The net additions followed a 4 GW net capacity decrease in 2015 — the largest net drop ever recorded in the country.

Over the last 15 years, natural gas made up most additions, accounting for nearly 228 GW, but 2016 was another year that saw renewables gain ground. Wind and Solar have made up an increasingly larger share of capacity additions in recent years. Wind added 8.7 GW last year, while solar added 7.7 GW. Natural gas added 9 GW.

The EIA said large amounts of new utility-scale wind capacity started entering the market in 2007 and have averaged 7 GW/year since “despite occasional lapses in available tax credits.” Other than 2014, utility-scale solar additions have increased in each year since 2008. The 7.7 GW of solar capacity additions in 2016 set a record. Not included in that total was the 3.4 GW of solar rooftop systems installed in 2016.

Since 2002, the power industry has retired more than 53 GW of coal capacity. About 20 GW of new coal capacity has been added in the past 15 years, while annual coal additions have been less than 1 GW in each of the last four years. About 54 GW of natural gas-fired capacity has retired since 2002 as well, the units were primarily older steam turbines and small gas turbines, EIA said.

There are dozens of new gas-fired plants under development or construction in Texas and the Mid-Atlantic — including Ohio and Pennsylvania. A rush is on to build more gas-fired power generation in the PJM Interconnection market in particular. One of the greatest pushes is underway in the Appalachian Basin, where cheap shale gas has prompted developers to pursue more gas-fired additions and replace aging plants.

A recent NGI special report, “Pipelines & Power: How New Infrastructure Could Uncork the Marcellus-Utica Bottleneck,” explores the trend and includes insights and more data about what increasing gas-fired electricity could mean for demand going forward.

The EIA said last month that if all the new gas-fired plants planned for this year and next come online, gas-fired generating capacity could reach its highest level since 2005. EIA said the power sector plans to increase gas-fired generating capacity across the country by 11.2 GW in 2017 and by 25.4 GW in 2018. Even if gas prices rise moderately during that time, the planned additions could help gas maintain its status as the nation’s primary source of electricity.

The EIA noted Monday that as more plants are retired and new ones come online, the ages of the country’s generating fleet will vary. Most operational coal plants, for example, were built before 1980 and a large portion of hydroelectric facilities are even older (the oldest operating was built in 1891). Most of the gas-fired fleet and nearly all of the nation’s wind and solar capacity has been built since 2000.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |