Regulatory | NGI All News Access

Sioux Tribes Ask Federal Court to Overturn Dakota Access Approval

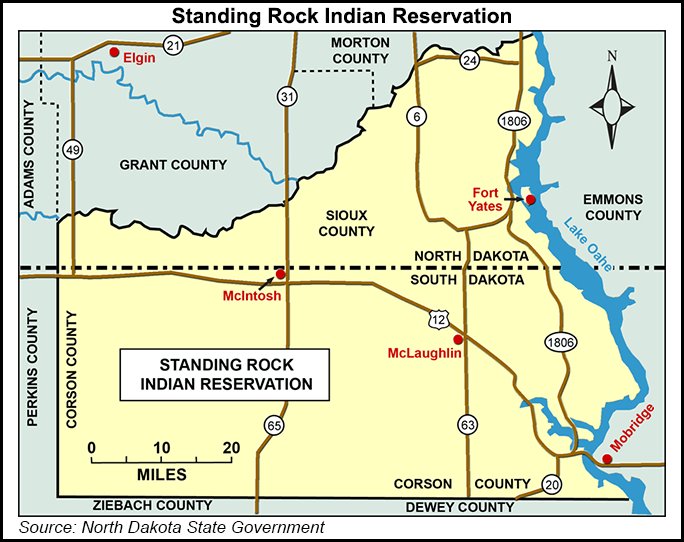

The Standing Rock and Cheyenne River Sioux Tribes on Tuesday filed a motion in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia to set aside the Trump administration’s approval to allow the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) to be completed at a Missouri River crossing in south-central North Dakota.

Sioux attorneys from the Earthjustice offices in Seattle asked a federal judge who has so far ruled against the DAPL opponents to rule on at least two major legal arguments: whether the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) was shortchanged in granting an easement to the pipeline constructors and whether the federal approval violated the U.S. government’s treaty with the tribes.

The filing seeks the court’s approval of a summary judgment regarding the easement that was granted over federal land by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Pipeline supporters indicate the line may be completed more quickly than previous 90-day estimates for the work.

“The judge appears ready to move forward on this case on an expedited basis,” according to a spokesperson for the Sioux.

Calling the Corps’ action a “hasty and an unexplained departure from its previous decision,” the lawsuit argues that the action ignored the treaty rights and will harm culturally significant and sacred sites. It alleges granting the easement also violated requirements for a thorough environmental assessment under NEPA.

“The Trump administration is circumventing the law,” said Earthjustice attorney Jan Hasselman, who is representing the Standing Rock Sioux. “The U.S. government must keep its promises to the [Tribe] and reject rather than embrace dangerous projects the undercut treaties.”

The plaintiffs’ attorneys cited the Fort Laramie treaties of 1851 and 1868 that they claim bound the U.S. government “to protect the Great Sioux Nation, or Oceti Sakowin,” which included large portions of North and South Dakota and other states.

The Midwest Alliance for Infrastructure Now (MAIN), a DAPL support group, lauded Judge James Boasberg for his denial last Monday of the Cheyenne River Sioux’ request for a temporary restraining order (TRO) to halt DAPL construction. MAIN noted that currently there are at least four other oil pipelines that cross the Missouri River north of proposed DAPL crossing.

As he had done last September, Boasberg denied the TRO request and said the Native American legal claims — particularly the Standing Rock Sioux, whose reservation is adjacent to the disputed water crossing under a dammed portion of the Missouri River — might better focus on blocking the oil pipeline from starting service.

As the judge was denying the TRO, the opposition was filing more lawsuits against DAPL, prompting MAIN spokesperson Craig Stevens to accuse the opponents of “throwing lawsuits against the wall in a flailing attempt to scuttle the project.” Stevens called the underlying motivation for all the legal action “an attack on America’s energy development.”

ClearView Energy Partners LLC’s Christi Tezak, managing director, said the opponents have two more chances to block the pipeline’s commercial start in the next six to eight weeks, but after that litigation would go on while DAPL is operating.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |