Infrastructure | E&P | Marcellus | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Rover Gets FERC Order Just in Time

East-to-west Appalachian natural gas mega project Rover Pipeline LLC finally has FERC’s blessing, securing approval to move forward with construction more than six months after getting its final environmental impact statement (FEIS).

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s order to grant Rover a certificate of convenience and necessity under Section 7 of the Natural Gas Act came late Thursday and not a moment too soon. With Friday marking Commissioner Norman Bay’s last day, FERC now heads into a quorumless stretch until new Commissioners can be appointed.

FERC’s order also approved the related Panhandle Backhaul and Trunkline Backhaul projects. Rover and the Panhandle and Trunkline projects are all backed by Energy Transfer Partners LP.

FERC wrote that the benefits Rover and the related projects “will provide to the market outweigh any adverse effects on existing shippers, other pipelines and their captive customers, and on landowners and surrounding communities.”

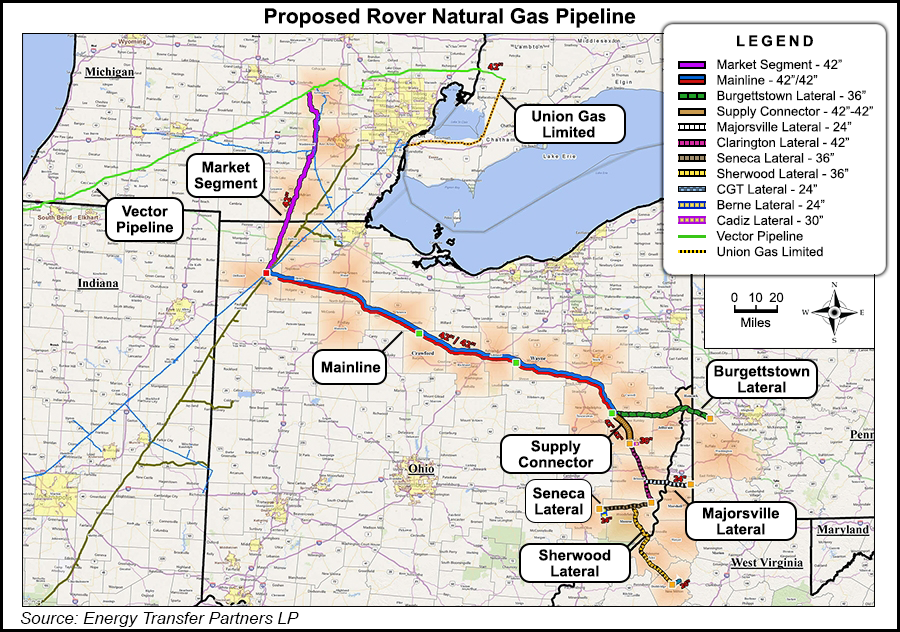

News of Rover’s approval will be music to the ears of Appalachian Basin producers looking forward to the 3.25 Bcf/d east-to-west the pipeline will offer. The 710-mile project will connect processing facilities in the Marcellus and Utica shales to the Midwest Hub in Defiance, OH, and then to interconnects with the Vector Pipeline in Michigan and to the Union Gas Dawn Hub in Ontario.

Analysts with Wells Fargo Securities said Friday that the capacity from Rover would especially benefit Antero Resources Corp., which has 800 MMcf/d reserved on the pipeline, and Range Resources Corp., which has 400 MMcf/d. Southwestern Energy Co. (200 MMcf/d), EQT Corp. (150 MMcf/d), Gulfport Energy Corp. (150 MMcf/d), Rice Energy Corp. (100 MMcf/d) and Eclipse Resources Corp. (100 MMcf/d) also have space on the project, according to analysts.

Ascent Resources LLC is the largest firm capacity holder on Rover, with 1.1 Bcf/d committed.

“There are certainly other snags that can delay the process, but getting FERC approval is a big deal,” NGI Director of Strategy and Research Patrick Rau said. “The real proof as to how likely any major producer-push project like this will progress can be judged by the actions of producers, since they will have to ramp up activity to fill that capacity.

“Midstream companies and producers work closely together, and those producers won’t ramp activity until they are confident about Rover’s ultimate in-service date. So look for more detail when those shippers that are publicly traded report earnings later in February.”

Energy Transfer had been planning to build and place the $4.2 billion Rover fully into service to Vector and the Dawn Hub by November of this year, with service to Defiance, OH, scheduled to begin this summer. But that timeline was based on a FERC certificate arriving by 4Q2016. Rover’s long wait for a federal authorization decision — the FEIS came down last July — raised the prospect of delays.

In December, Energy Transfer urged FERC to issue an order by the start of 2017. Tree-clearing would need to start by mid-January, the company wrote, or else the project “very likely will be delayed for up to a full year.”

In statement Friday afternoon, Energy Transfer reaffirmed its original project schedule: “Consistent with its previous statements, Rover anticipates that it can meet its targeted in-service goals of July 2017 for Phase I [to Defiance] and November 2017 for Phase II [to Vector and Dawn],” the company said.

Rover’s review hit a snag when FERC learned last fall that the company had demolished the historic Stoneman House in Ohio without notifying the Commission. The home was located near a proposed compressor station and would have fallen within the visual area of potential effects for the project.

In Thursday’s order, FERC scolded Rover for its demolition of the house and consequently denied its request for a blanket certificate under Part 157, Subpart F to conduct routine construction activities “without the need to obtain a case-specific certificate for each individual undertaking.

“…Because this program allows natural gas companies to undertake certain construction activities, in some cases without even prior notice to the Commission, it depends on the Commission’s confidence that a natural gas company will not act contrary to the Commission’s regulations and other environmental statutes,” FERC wrote.

“Rover’s intentional demolition of the Stoneman House raises the question of whether Rover would fully comply with our environmental regulations in future construction activities under a blanket certificate.”

The denial means “Commission staff will be able to fully analyze the environmental impacts of Rover’s construction that would otherwise occur pursuant to a blanket certificate, prior to the company’s being authorized to proceed,” the Commission wrote.

Rover can reapply for a blanket certificate 18 months after starting commercial operations, FERC said.

FERC’s response to the Stoneman House demolition could have been worse, and it might not have an impact on the construction timeline, according to an analysis by Clearview Energy Partners.

“FERC could have withheld approval of the entire project on the farmhouse issue alone, as the Commission found that the demolition constituted a violation of the National Historic Preservation Act,” ClearView noted Friday. “…This lack of blanket certificate authority may not necessarily affect the project’s initial construction timeline. Blanket certificate-related work often occurs after the project is in service.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |