Infrastructure | NGI All News Access

Biomass, Not Coal, Part of Oregon’s Energy Future

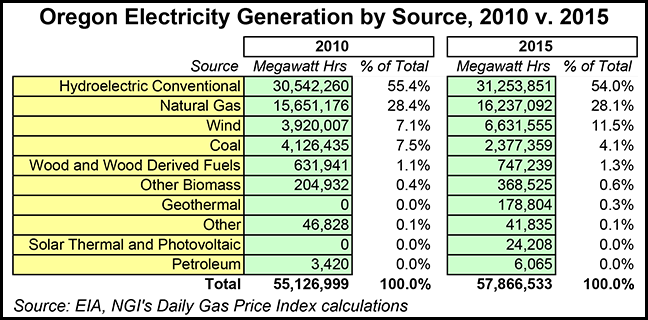

Along with several new natural gas-fired power plants, biomass is being explored as an alternative to coal in Oregon, where utilities and state officials have agreed to phase out coal use.

As a result, Portland General Electric’s (PGE) coal-fired plant at Boardman, OR, is being used occasionally as a virtual test laboratory for perfecting an advanced technology for transforming a coal-fired generation facility.

PGE engineers are exploring the possibility of converting the state’s lone remaining coal-fired electric generation plant to burn wood waste biomass, because it could be more efficient than converting the 560 MW Boardman plant to natural gas. The key is an advanced biomass process called “torrefaction.”

Since 2015, PGE has been experimenting with various co-firings of biomass and coal, leading up to a 100% biomass test as early as the first quarter of 2017, a Portland-based PGE spokesperson told NGI.

“In addition to regulatory requirements, there are significant operational challenges to overcome before a Boardman biomass option can be seriously considered,” PGE officials contend, noting that the coal-fired plant is slated to close by the end of 2020.

What is clearly known to PGE engineers is any new biomass plant at Boardman will require 8,000 tons of fuel daily, and there are many potential sources of biomass. The utility has been working with Oregon State, Washington State, Portland State and the University of Washington to look at all of the options.

Raw pellets usually used in domestic wood stoves and co-firing power plants don’t work well with Boardman’s equipment, the PGE spokesperson said, pushing the utility to use torrefied technology, which provides a roasting process similar to how charcoal is produced. “The end result is a dry, brittle material that can be pulverized and used for fuel at Boardman with minimal changes to the existing plant’s equipment,” the spokesperson said.

PGE has conducted at least four co-firing tests using the torrefied biomass product since November 2015. Although it had hoped to complete a 100% test in December, it had to settle for three additional co-firing test burns on three separate days in the last month of the year.

“After the first test, we determined that additional tuning was necessary to adapt the plant’s pulverizers to use the torrefied fuel,” the PGE spokesperson told NGI, adding that utility engineers did that and had good results in the subsequent two test burns. “Safely pulverizing the fuel, injecting it into the boiler and combusting it to help fuel the plant all worked well,” he said.

Given some of the coldest weather in Oregon for the year in December and the prospects for more, PGE decided to hold off making modifications to other pulverizers that are needed for a 100% biomass burn.

“We still intend to proceed with that test, but will schedule it as plant operations allow, using the fuel we have on hand,” he said. “We’re targeting the first quarter, but that will depend on plant availability and possible additional co-firing test burns.”

It’s a continuing learning process as the PGE engineers refine their understanding of how the biomass fuel behaves with Boardman’s equipment, the spokesperson said.

Last January, the state’s two major electric utilities and a coalition of environmental groups agreed to phase out coal-fired generation between 2030 and 2035, leaving out any mention of the future role for natural gas in the power mix, although its use still could expand. More recently, PGE opened a 440 MW gas-fired generation plant last summer near Boardman.

Also early in 2016, the Oregon legislature passed SB 1547, eliminating essentially all use of coal-fired electricity by 2030 while expanding goals for renewable energy, efficiency and electric-based transportation in the state by 2040.

In anticipation of the coal plant closure, an Oregon-based company, HM3, unveiled technology that could help convert coal-fired power plants globally to biomass boosted by its technology for torrefaction.

At a grand opening of its $4 million Troutdale, OR, demonstration plant in 2016, HM3 told local news media that it had “cracked the code” on torrefaction, a concept that got a lot of attention early this decade but has been set back as companies have struggled to produce fuel consistently and economically in test-scale ventures.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |