Shale Daily | Bakken Shale | E&P | Eagle Ford Shale | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Permian Basin

Drilling in the ‘Permian Mother Lode…for the Next 100, 150 Years,’ Says Pioneer CEO

The Permian Basin is and will remain the key oil resource of the U.S. onshore because its deep and varied formations hold at least a century’s worth more of resource opportunities that eclipse any other part of the country, Pioneer Natural Resources Inc. CEO Scott Sheffield said Tuesday.

“The Permian is the mother lode. You factor in 4,000 feet of shales with 12 to 14 zones to play with…We’ll be drilling that for the next 100, 150 years.”

Sheffield, who has run Pioneer since it was formed in 1997, shared his views of the oil and gas market — past, present and future — at an event hosted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, DC. The event was moderated by Sarah Ladislaw, who directs the CSIS Energy and National Security Program.

The current energy market downturn is Sheffield’s fifth since 1981, a balancing act that has taught him a thing or two about how to remain viable.

Being in the “best places” helps, as does having a great balance sheet. “Every seven or nine years there’s a downturn, caused by too much supply or something like the mortgage crisis…You have to be prepared for that” by not piling on too much debt, he said. Throw in aggressive hedging and the wherewithal to revamp when necessary for more leverage.

No exploration and production (E&P) company is going to make it out of the downturn unscathed. More than two dozen U.S. E&Ps have declared bankruptcy this year alone. “I’ve seen $62 billion worth of bankruptcies in the upstream, and it’s worse on the services side,” Sheffield said. “We have more cash on the balance sheet than most of the majors today. That’s why there’s not been a lot of merger and acquisition activity, in my opinion.”

Recovery will take time

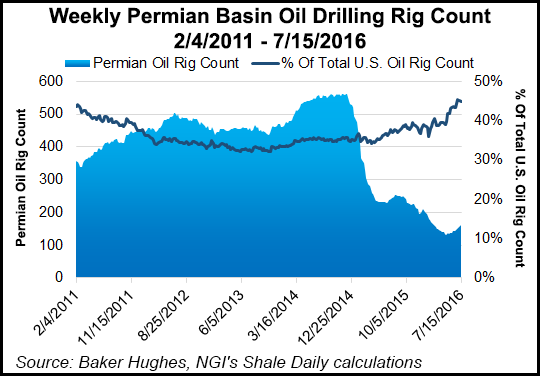

An estimated $33 billion in equity, he noted, has been raised by E&Ps — and nearly all of it is going to fund Permian Basin operations. Coming out of the downturn may be a bit easier in West Texas, but the “totally decimated” oilfield services sector means it’s going to take longer to get things going again. Sheffield estimated it could take three years before the U.S. rig count actually begins to strengthen. The latest uptick in rigs is nothing, he said.

“It’s still a flat rig count. If we have $60 oil next year, and I expect that next year, it will take another 12 months to add back rigs. So there will be no increase in U.S. production until 2018 at the earliest…It takes five months just to add the first drop of oil after adding a rig,” as most producers drill multi-well pads now. That means all of the wells have to be drilled and completed before they are tied into. “It used to take two weeks on a single vertical well. Now it takes five months.”

It’s going to be a rough time for E&Ps for a long time. Once drilling begins to ramp up, don’t expect to see strong output growth from the Bakken or Eagle Ford shales again, Sheffield said.

“You have to look at where oil rigs are today,” and basically that’s only the Permian’s Delaware and Midland sub-basins, and Oklahoma’s stacked reservoirs.

The Dallas-based independent’s operations illustrate the point. Exploration efforts once stretched worldwide, comprising about 60% of its business, but the Barnett Shale changed the map. After “dabbling” in the North Texas field, Pioneer in 2009 drilled its first horizontal well in the emerging Eagle Ford Shale in South Texas. The next year, a well was bored into the Permian’s Spraberry formation.

The unconventional bug quickly spread.”We divested all of our international acreage and refocused on West Texas and South Texas,” Sheffield said. “It surprised us, but it was a home run, and we had to make that strategic change…”

Permian course set in 2011

Asked when his “aha moment” occurred, Sheffield said it was during a staff meeting in 2011. A geologist told management that Pioneer had an estimated 10 billion bbl net of reserves in its Permian acreage alone, which was about 900,000 acres. “It blew our minds…”

Pioneer has never looked back, but there’s no doubt the oil price downturn slowed the company and its peers. But it’s also given producers time to finesse fractures (frack), lateral lengths and the entire drilling process.

“We’re all asked about where the few sweet spots are in the Permian Basin,” the CEO said. “It turns out almost our entire position is a sweet spot. What’s changed in the last two years is that all of us were thinking about maximum frack heights of 300-400 feet, 10,000 foot long wells. We are realizing that there is so much oil and gas in place, it’s better to focus nearest the wellbore.

“Right now, we are seeing stages increase…seeing more sand, more water, reduced spacing, and we are adding more clusters within the frack stage. The goal is the break up more rock nearest the wellbore.”

Competitors in the Permian are drilling “better and better wells,” and breaking up the rocks near the wellbore. The method is proving consistent not only in the Permian, but in the Marcellus and Utica too, he said. “As everyone changes their mindset, they will break up more rock nearest the wellbore.”

For Pioneer, its average operating cost for a horizontal well in the Midland is $4/bbl, with a finding cost of $10. General and administrative costs add another $5.00.

Eagle Ford and Bakken don’t stack up

“The margin is $19/bbl, and anything above that is profit for us. That’s why we’re running 17 rigs today. We have a 35-45% return, based on strip pricing” of around $45/bbl. “The Eagle Ford doesn’t stack up, economically. The Bakken doesn’t stack up. That’s why there is so little activity in those plays.”

What happened in the Bakken and Eagle Ford is instructive, as they were the first big onshore oil plays to take off. Producers in the Bakken and Eagle Ford “got very aggressive…and they went too fast” because they didn’t have acreage held by production. “Normally, you wouldn’t have drilled as fast. And that’s what happened in those good plays…” Meanwhile, in the legacy Permian, where leaseholds have been held for decades, operators have been able to pace themselves.

“When prices get back to $55-60, the rigs will get back to work” in the Bakken and Eagle Ford, but “they will be lucky to keep production flat.” The Bakken has differential issues, while the Eagle Ford is much gassier in general.

“That’s why the Permian is the mother lode. You factor in 4,000 feet of shales, 12 to 14 zones to play with. The Eagle Ford only has one or two zones and it’s 250-feet thick. That’s why the Permian sticks out.”

All things being equal, Pioneer would do well if it only had the Permian, Sheffield said.

“When you look at the Permian, it is growing 30% a year for us, and the company is only growing 13-14% a year because we have other assets that are declining and we’re not putting money into. We have conventional stuff. Nobody’s spending on that and it’s low margin. Any time you add natural gas or liquids, it reduces margins. Every company has this, and over time, it will be sold.

“If we only had the Permian we could grow 15-20% a year over the next 10 years at strip prices.” In fact, $55-60/bbl oil prices long term “is fine with us,” and in some ways, better than if oil prices were to move to an average of $70-80.

The Permian has the potential to produce up to 7 million b/d, and could get to 5 million b/d “easily,” Sheffield said. Of course, the Permian cannot fuel the country, much less the world. The oil and gas industry has to fund more investments or face certain production declines within a couple of years. Where there were an average of 50 major projects started around the world in recent years, there were only 10 last year.

“Eventually that’s going to catch up with us,” the CEO said. “The U.S. would be much worse off,” except production from the Gulf of Mexico has risen as new projects are starting up. The crisis point is going to come around the end of 2017 through 2018-19 when few new projects are coming on. “Are we going to set ourselves up for another shock? The Permian isn’t going to save the rest of the world.”

Electric car future?

The petroleum engineer remains a “firm believer that we should look at all sources of energy,” not just oil and gas. “We need more capital in nuclear, solar, wind.” Sheffield said he has a home in new Mexico that has solar. And the company uses wind for most of its pumping units for electricity in West Texas.

“The industry wants to be balanced…If not for shale, we would have peaked in 2007. How long shale will go on, and for what period of time? It’s too expensive in the rest of the world…An international shale well costs three times as much as a U.S. well. There’s less competition for services, no infrastructure, no pipelines…”

Over the long term, he thinks the evolution will be centered around alternative energies and electric cars. “Not for the next five years, but 10, 20, 30 years from now it will be interesting to see how the gasoline engine evolves to electric cars…I’ve been in a Tesla. It’s quiet, it’s nice. But in Texas, it won’t take you very far. But the movement is to keep going…There will be some big breakthrough.” He suggested someone like Google or Apple would have to buy Tesla to inject the necessary amount of capital to push development into high gear.

Regardless, the global population is growing and hydrocarbons are going to remain a “major” force. “But I do see a scenario where we have peak oil demand…and the best margin plays will be fighting for the next barrel.”

Price-wise, Sheffield is a “firm believer” that oil will get to $70-80/bbl at some point, but in the “long term,” the average probably will be closer to $55-60.

Sheffield declined to pick a horse in the current political race, saying the industry worked to educate all the politicians on energy. He added, however, that his company had done best during Democratic regimes, citing Pioneer’s results from 2009 through the end of 2014.

Asked his views on a carbon tax, Sheffield said he would support it “if every country in the world agreed to it at the same time, but the chances of that happening are very slim.” It would be untenable if only the United States adopted it, since it would move all the capital out of the country into the international market.

Pioneer is still hiring, Sheffield said, adding he believed his company and Continental currently are the most active drillers.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |