Regulatory | Infrastructure | NGI All News Access

Canada’s NEB Says TransCanada Mainline Conversion Application Complete

After three years of industry bargaining, community meetings, aboriginal consultations and route changes, TransCanada Corp. Thursday won the first round in the battle over the proposed Energy East partial conversion of its natural gas Mainline to oil service.

The National Energy Board (NEB) opened the regulatory door to approval of the C$15.7 billion (US$12 billion) project — at a much brisker pace — by accepting the construction application as complete. The formal, law court-like review has to be finished inside a legislated limit of 21 months, with a decision by March 16, 2018.

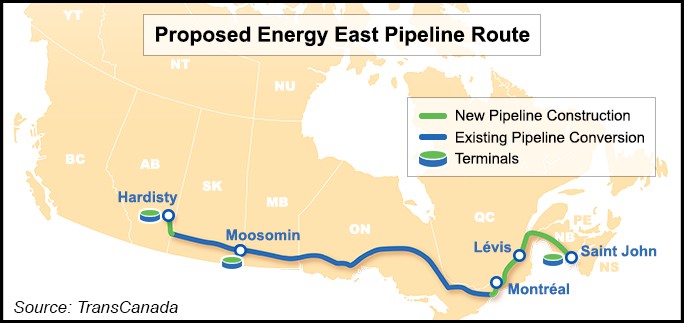

The acceptance ruling was anything but merely a routine step for the plan to deliver 1.1 million bbl of Alberta oil per day via 3,000 kilometers (1,800 miles) of converted gas Mainline to Quebec plus a 1,520-kilometer (912-mile) extension to a tanker dock beside Canada’s biggest refinery in Saint John, New Brunswick. The decision includes a related application for TransCanada’s Eastern Mainline proposal to replace lost gas delivery capacity in Ontario.

Energy East President John Soini called the NEB ruling “an important and welcomed milestone in what has so far been three years of scientific analysis, study and engagement with thousands of Canadians along the route since the project was first announced.”

The accepted package, a 39,000-page plan in 25 volumes, includes 700 route changes made since the first draft was filed in the fall of 2014. TransCanada also resolved a major environmental dispute by dropping plans for a Quebec tanker terminal at a spot on the St Lawrence River near a treasured beluga whale breeding area (see Daily GPI, Dec. 21, 2015).

The proposals include a settlement of a months-long dispute over replacement gas service and costs with Ontario and Quebec distribution companies.

In Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and northwestern Ontario the partial conversion is a money-saving, toll-reducing use for excess gas capacity in the Mainline by putting oil into one of multiple pipelines in its right-of-way.

But for southeastern Ontario and Quebec, Energy East spelled lost capacity for low-cost imports of shale gas from the United States. The settlement that supports the Eastern Mainline, a 279-kilometer (167-mile) line for short hauls of high gas volumes, makes TransCanada pay for replacement service and only charges the distributors for additional transportation bookings.

Since the initial project announcement and sketchy outline in mid-2013, TransCanada reported holding 139 community events that drew total attendance of 11,000. Information is being provided to 329 local emergency response agencies along the route.

The pipeline company has been in touch with 166 aboriginal communities and is co-operating on 66 traditional knowledge studies to identify and protect culturally sensitive locations. Separate, special oral hearings are under way for native groups that prefer not to be required to distill their thoughts into written documents.

The formal regulatory review, scheduled to start Aug. 8 in Saint John, will include an arena for expressions of community, aboriginal and environmental opinion presided over by new NEB members that the government plans to appoint this summer.

Board official Jean-Denis Charlebois told a news briefing at the agency’s Calgary headquarters, “All Canadians who wish to take part in the decision on this project will be heard. This review will be unlike any other in the NEB’s history [since its birth in 1959].”

Federal Natural Resources Minister Jim Carr added a brief statement that in Canada, “Major resource projects must go through a review and consultation process that carries the public trust, and today marks a key milestone in that process.”

The sorest spot in the Energy East package is that most and possibly all of the pipeline conversion cargo is expected to come from Alberta’s oilsands, which makes the project a Canadian counterpart to TransCanada’s rejected Keystone XL proposal in the United States.

Opponents immediately fired off statements that no amount of explanation, consultation and listening would clear away all the resistance against Energy East. The Kanesatake Mohawks in the Ottawa Valley and the Wibun Tribal Council First Nations in northern Ontario called the completeness ruling on the project application a mistake in their cases. The Assembly of First Nations of Quebec and Labrador formally declared opposition to the project and repeated demands for aboriginal veto power over industrial projects that stray anywhere near native territory. Greenpeace, claiming to represent a national array of environmental groups, vowed to fight the project to its death.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |