Markets | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

NatGas Prices Higher in 2017 But Flat Until Appalachia Gives Way to Older Shale Basins, Bernstein Says

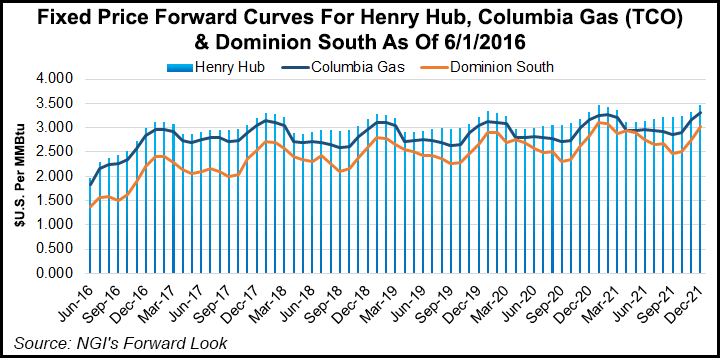

U.S. natural gas prices should average $3.00/Mcf in 2017 but remain flat until after 2020, when supply sources beyond the mighty Appalachian Basin will be called upon to meet rising demand, Sanford Bernstein analysts said Tuesday.

The macro outlook, in line with the forward strip, sees prices “capped near $3.00/Mcf through this decade as associated gas reemerges” on rising crude oil prices, wrote Jean Ann Salisbury, Bob Brackett, Samuel Shrank and Jackson Kulas. Enough existing gas infrastructure exists in Appalachia and other basins to meet demand until the middle of the next decade.

Previously, analysts had forecast gas prices would average $2.75/Mcf in 2016, but they reset the average price this year to $2.25. For 2018, the previous forecast was $3.25, with an average of $3.35 in 2019. The updated price deck is near consensus, with the Energy Information Administration forecasting 2016 gas prices will average $2.25 (see Daily GPI, May 10). Goldman Sachs expects Henry Hub this year to average $2.46/MMBtu, with 2017 and 2018 gas prices averaging $3.00 (see Shale Daily, May 23).

Bernstein said the consensus has missed “crucial” elements of the supply/demand story over the next decade. It’s not going to be all about the Marcellus and Utica shales anymore, they said.

“We believe that rising demand over the next decade will push the industry up the supply cost curve, boosting price and benefiting producers and the midstream alike,” Salisbury said. Gas demand from 2015-2020 is expected to grow by 16 Bcf/d, or 3.6% compound annual average. From 2020 to 2025, gas demand growth is seen rising by 15 Bcf/d.

The price outlook is based on assumptions that:

“Over the medium term, we forecast that gas price will be determined by associated gas produced and the resulting call on the southwestern Marcellus/Utica,” the analysts said. “The southwestern Marcellus has wide variability within it, with breakeven gas price ranging from less than $0/Mcf in the liquids-rich parts of the play to more than $5.00/Mcf at the margin.

“As demand growth emerges, we forecast that gas will rise to $3.00/Mcf to meet it. However, the return of associated gas growth in 2018 will keep price near this level through 2021, when a return to second-tier basins will move the price closer to $4.00/Mcf.”

Production growth should fill new pipeline capacity in Appalachia through 2022, “after which the region will no longer be able to deliver growth,” according to Bernstein. Once Appalachia again runs into infrastructure constraints, demand will have to be filled by other gas basins around the country.

“We generally believe that the Rockies are too out of the money for it to grow substantially, even treating gathering and transport as sunk,” analysts said. “However, the Haynesville, Fayetteville and Barnett are all marginal.” There may be “another 4 Bcf/d of capacity from the Haynesville that could be ramped up with gathering already sunk, and another 1.5 Bcf/d from the Barnett. The Fayetteville is only off 0.5 Bcf/d from the peak but could probably add back these volumes before incremental midstream investments would be required.”

Gas supply from associated gas, wells that aren’t horizontals, offshore and Alaska are forecast to decline to 2025, with incremental demand met through the increased call on older shale gas basins.

Once the U.S. onshore gas basins produce a combined 49 Bcf/d — the total infrastructure capacity of the group — incremental production is expected to require new infrastructure construction. Bernstein’s base case model suggests that this should occur in 2022, effectively pausing midstream expansion until then.

“This assumes that all contracted LNG leaves U.S. shores,” the analysts said. If there are lower LNG exports, the need to build more infrastructure would be deferred beyond 2025.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |